Ivan Franko facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ivan Franko

|

|

|---|---|

Franko in 1910

|

|

| Native name |

Іван Якович Франко

|

| Born | 27 August 1856 Nahuievychi, Austrian Empire (now Ukraine) |

| Died | 28 May 1916 (aged 59) Lemberg, Austria-Hungary (now Lviv, Ukraine) |

| Resting place | Lychakiv Cemetery |

| Pen name | Myron, Kremin, Zhyvyi |

| Occupation | poet, writer, political activist |

| Language | Ukrainian, Polish, German, Russian |

| Education | Franz-Josephs-Universität Czernowitz University of Vienna (PhD, 1893) |

| Period | 1874–1916 |

| Genre | epic poetry, short story, novels, drama |

| Literary movement | Realism, Decadent movement |

| Spouse |

Olha Fedorivna Khoruzhynska

(m. 1886) |

| Children | Andriy Petro Franko Taras Franko Hanna Klyuchko (Franko) |

Ivan Yakovych Franko (Ukrainian: Іван Якович Франко; 27 August 1856 – 28 May 1916) was a very important Ukrainian poet, writer, and thinker. He was also a social critic, journalist, and translator. Franko was an economist, political activist, and a doctor of philosophy. He was also an ethnographer, someone who studies cultures and customs. He wrote the first detective novels and modern poetry in the Ukrainian language.

Franko was a political radical, meaning he wanted big changes in society. He helped start the socialist and nationalist movements in Western Ukraine. Besides his own writing, he translated works by famous authors like William Shakespeare, Lord Byron, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe into Ukrainian. His translations were even performed in the Ruska Besida Theatre. Along with Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko greatly influenced modern Ukrainian literature and political ideas.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Ivan Franko was born in 1856 in the Ukrainian village of Nahuievychi. At that time, it was part of the Austrian Empire. When he was a baby, he was baptized as Ivan. However, his family called him Myron because of a local belief that a different name could protect him from bad luck. His family was quite well-off, owning land and having servants.

Franko's family might have had German roots. His great-grandfather was part of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. His mother, Maria, came from a family of petty nobility, which means they were a lower rank of noble people.

Ivan went to school in Yasenytsia Sylna from 1862 to 1864. Then he attended a monastic school in Drohobych until 1867. His father passed away before Ivan finished high school, but his stepfather helped him continue his studies. Later, his mother also died, and young Ivan had to live with other people. In 1875, he finished school in Drohobych and went to University of Lviv. There, he studied classical philosophy, Ukrainian language, and literature. This is where he started his writing career, publishing poems and a novel in the student magazine Druh (Friend).

Political Activism and Arrests

At Lviv University, Ivan Franko met Mykhailo Drahomanov, a meeting that greatly influenced him. Their friendship led to a long partnership in politics and writing. Franko's socialist writings and his connection with Drahomanov led to his arrest in 1877. He was accused of being part of a secret socialist group, which actually didn't exist. Even after spending nine months in prison, he didn't stop his political writing. While in prison, Franko wrote a satire called Smorhonska Akademiya.

After being released, he studied the ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He wrote articles for a Polish newspaper and helped organize workers' groups in Lviv. In 1878, Franko and Mykhailo Pavlyk started a magazine called Hromads'kyi Druh ("Public Friend"). The government quickly banned it, but it reappeared under new names, Dzvin (Bell) and Molot (Mallet). Franko was arrested again in 1880 for encouraging peasants to protest. After three months in prison, he returned to Lviv. His experiences from this time are shown in his novel Na Dni (At the Bottom). Because of his political views, he was later expelled from Lviv University.

Later Career and Family Life

In 1881, Franko was a main writer for the journal Svit (The World). He wrote more than half of its content. Later that year, Franko moved back to his home village, Nahuievychi. There, he wrote the novel Zakhar Berkut and translated famous works like Goethe's Faust into Ukrainian. He also wrote articles about Taras Shevchenko.

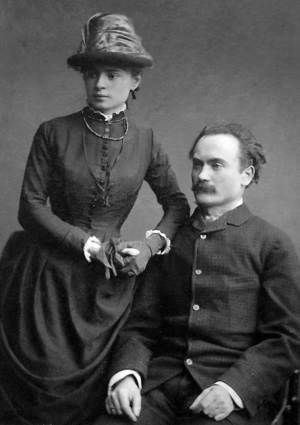

In May 1886, Franko married Olha Khoruzhynska from Kyiv. He dedicated a collection of his poetry, Z vershyn i nyzyn (From Tops and Bottoms), to her. The couple lived in Vienna for a while. Sadly, Olha later suffered from a serious mental illness, especially after their first son, Andriy, passed away.

In 1888, Franko wrote for the journal Pravda. His connections with writers from other parts of Ukraine led to his third arrest in 1889. After two months in prison, he helped start the Ruthenian-Ukrainian Radical Party. Franko tried to win elections for the Austrian parliament, but he never succeeded.

In 1891, Franko studied at the University of Chernivtsi and then at the University of Vienna. He earned his doctorate degree in philosophy from the University of Vienna in 1893. He became a lecturer at Lviv University in 1894, teaching Ukrainian literature. However, he couldn't become the head of the department because of opposition from some conservative groups.

In 1898, Franko published an article criticizing Karl Marx's ideas about socialism. He continued this view in his poetry collection Mii smarahd (My Emerald), calling Marxism "a religion founded on hatred and class struggle." His friendship with Mykhailo Drahomanov became difficult because they had different ideas about socialism. In 1899, Franko helped found the National Democratic Party and worked there until 1904, when he left political life.

In 1902, students and activists in Lviv bought a house for Franko because he was living in poverty. He lived there for the rest of his life. Today, this house is the Ivan Franko Museum.

In 1904, Franko joined an expedition to study the culture of the Boykos, a Ukrainian ethnic group. In his last nine years, Franko could barely write by hand because of a condition that paralyzed his right arm. His sons helped him write down his thoughts. In 1916, people tried to nominate Franko for the Nobel Prize in Literature, but he passed away before it could happen.

Death

Ivan Franko died in poverty on 28 May 1916. He was buried at the Lychakivskiy Cemetery in Lviv. His admirers paid for his burial and clothes.

Family

Wife

Olha Fedorivna Khoruzhynska (married 1886, died 1941) was a smart woman who knew several languages and played piano.

Children

- Andriy Franko (1887 - 1913) - died young from heart problems.

- Petro Franko (1890–1941) - an engineer, a veteran of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (a military unit), and a Ukrainian politician. He helped found the Ukrainian Air Force.

- Taras Franko (1889 - 1971) - also a veteran of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen.

- Roland Franko (1931-2021) - a Ukrainian politician and diplomat. He helped transfer a British Antarctic research station to Ukraine, which was renamed Academician Vernadsky.

- Zenovia Franko (1925-1991) - a Ukrainian language expert and an important figure in the Ukrainian nationalist movement during Soviet times.

- Hanna Klyuchko (Franko) (1892 - 1988) - a Ukrainian writer.

Ivan Franko was about 1.74 meters (5 feet 8 inches) tall, had red hair, and always wore a mustache and a traditional Ukrainian embroidered shirt (vyshyvanka). Some of his family members later moved to the US and Canada. His grand-nephew, Yuri Shymko, became a Canadian politician and human rights activist.

Literary Works

Franko's early works, like Lesyshyna Cheliad and Dva Pryiateli (Two Friends), were published in 1876. His first poetry collection was Ballads and Tales.

He wrote about the difficult lives of Ukrainian workers and peasants in novels like Boryslav Laughs (1881–1882) and Boa Constrictor (1878). His works also explored Ukrainian nationalism and history, such as Zakhar Berkut (1883). He wrote about social issues in Basis of Society (1895) and Withered Leaves (1896), and about philosophy in Semper Tiro (1906).

In Moses (1905), he compared the ancient Israelites' search for a homeland to Ukraine's desire for independence. His play Stolen Happiness (1893) is considered one of his best. In total, Franko wrote over 1,000 works!

He was very popular in Ukraine during the Soviet era, especially for his poem "Kameniari" (meaning "groundbreakers" or "rock breakers"). This poem had revolutionary ideas, earning him the nickname Kameniar.

Works Translated into English

Many of Ivan Franko's works have been translated into English, including:

- "What is Progress"

- "How a Ruthenian Busied Himself in the Other World"

- "Mykytych's Oak Tree"

- "Hryts and the Young Lord"

- "Unknown Waters"

- "Fateful Crossroads"

- "For the Home Hearth"

- "From the Notes of a Patient"

- "Amidst the Just"

- Zakhar Berkut (also available as an audiobook)

A collection of his short stories and novellas called Faces of Hardship was published in 2021.

Legacy

In 1962, the city of Stanyslaviv in Western Ukraine was renamed Ivano-Frankivsk to honor the poet. As of 2018, there were 552 streets named after Ivan Franko in Ukraine.

He is also known by the name Kameniar because of his famous poem, "Kameniari" ("The Rock Breakers"). In 1978, an astronomer named an asteroid after him, calling it 2428 Kamenyar.

Ivan Franko's influence also reached North America. Cyril Genik, who was Franko's best man at his wedding, moved to Canada. Genik became the first Ukrainian to work for the Canadian government as an immigration agent. He and his cousins, inspired by Franko's ideas of nationalism, helped Ukrainians in Canada find their own identity. Today, a statue of Ivan Franko stands in Winnipeg, Canada, showing his lasting impact.

Ukrainian composer Yudif Grigorevna Rozhavskaya (1923-1982) used Franko’s words for her songs. In 2019, a Ukrainian-American action film called The Rising Hawk was released. It was based on Ivan Franko's historical fiction book Zakhar Berkut.

See also

In Spanish: Iván Frankó para niños

In Spanish: Iván Frankó para niños

- Ivan Franko Museum

- Ivan Franko International Prize

- Omelian Hlibovytskyi

- Ivan Kuziv

- Ostap Nyzhankivsky

- Ivan Popel

- Oleksa Volianskyi

- List of Ukrainian-language poets

- List of Ukrainian-language writers

- List of Ukrainian literature translated into English

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |