J. Marion Sims facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

J. Marion Sims

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

James Marion Sims

January 25, 1813 |

| Died | November 13, 1883 (aged 70) Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Jefferson Medical College |

| Occupation | Surgeon |

| Spouse(s) | Theresa Jones |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

James Marion Sims (born January 25, 1813 – died November 13, 1883) was an American doctor who specialized in surgery. He is known for creating the first hospital just for women in New York. He also played a part in starting the first cancer hospital in the United States.

Sims became one of the most famous doctors in the country. He was even elected President of the American Medical Association in 1876. He was also one of the first American doctors to become well-known in Europe.

However, there are serious ethical questions about how he developed his surgical methods. He performed operations on enslaved black women without using anesthesia. These women could not truly agree to the surgeries because they were not free to refuse. Today, many people see this as wrong. They believe it was an improper use of people for experiments, especially a group that was already vulnerable. A statue honoring him in New York City was removed in 2018 due to these concerns.

Sims wrote many reports about his medical experiments. He also wrote a 471-page story about his own life. These writings are the main sources of information about him. In recent years, people have started to look at his story differently.

Contents

Early Life and Medical Training

James Marion Sims, who liked to be called "Marion," was born in Lancaster County, South Carolina. His father, John Sims, fought in the War of 1812. His family lived in Lancaster Village for his first 12 years.

In 1825, Sims went to Franklin Academy. He later studied at South Carolina College. In 1834, he moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He then enrolled at Jefferson Medical College, graduating in 1835. Sims later said he wasn't very interested in medicine at first. He just wanted to make a living.

After medical school, Sims returned to Lancaster to practice. His first two patients died, which made him feel very sad. He then moved to Mount Meigs, near Montgomery, Alabama. He described Mount Meigs as a rough settlement. He stayed there from 1835 to 1837. In 1836, Sims married Theresa Jones, whom he had known for many years.

In 1837, Sims and his wife moved to Cubahatchee, Alabama. He worked as a "plantation physician." This meant he treated people on large plantations. He became known for operations on clubfeet, cleft palates, and crossed eyes. This was his first time treating enslaved black women.

Building a Reputation in Montgomery

In 1840, Sims and his wife moved to Montgomery, Alabama. He described this as the "most memorable time" of his career. Within a few years, he had the biggest surgical practice in the state. He was very popular and well-liked.

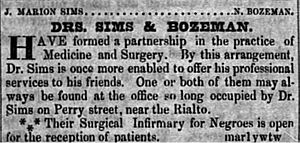

In Montgomery, Sims continued to treat enslaved people. They made up two-thirds of the city's population. He built a hospital, or "Surgical Infirmary for Negroes," for women whose owners brought them for treatment. It started with four beds and later expanded to eight or even twelve beds. Some call it the "first woman's hospital in history." It was also the first hospital specifically for Black people in the U.S.

In 1840, the medical field of gynecology did not exist. Doctors had no special training in it. They often learned about childbirth using dummies. Many doctors, including Sims, found examining female organs unpleasant.

Ethical Concerns and Experiments

From 1845 to 1849, Sims began doing experiments on enslaved black women. He aimed to treat their health problems, especially a condition called fistula. He treated these women at his own expense in his backyard hospital. Their owners brought them to him.

Medical Experiments on Enslaved Women

Sims named three enslaved black women in his autobiography: Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy. All three suffered from fistula. They were part of his surgical experiments. From 1845 to 1849, he operated on each of them many times. He operated on Anarcha 30 times before his treatment was successful. Sims even had his patients help him with operations when his doctor assistants left.

Anesthesia Use During Surgeries

Sims did not use any anesthetic during his procedures on Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy. Anesthesia was a new idea at the time. It was not widely known or accepted until 1846. Some doctors believed black people did not feel as much pain as white people.

Anesthesia was also still experimental and risky. It could be dangerous if too much was given. Surgeons in Sims' time were trained to operate very quickly on patients without anesthesia.

One patient, Lucy, almost died from sepsis, a serious infection.

After many experiments, Sims finally improved his technique. He successfully repaired Anarcha's fistulas. He was the first to use silver wire as a suture. This helped prevent infections that happened with silk sutures. He published his findings in 1852.

Later, Sims moved to New York and founded a Woman's Hospital. There, he performed the same operation on white women. Some sources say he used anesthesia for white women. However, other sources state that as late as 1857, Sims did not use anesthesia for fistula surgery on white women. He said the operations were "not painful enough to justify the trouble and risk." This view was common among surgeons who started practicing before anesthesia became widespread.

Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsy are remembered today. A statue called "Mothers of Gynecology" was put up in Montgomery, Alabama, in 2021 to honor them.

Treating Trismus Nascentium

In his early medical career, Sims also studied trismus nascentium. This is also known as neonatal tetanus, a serious disease in newborns. In the 19th century, this disease was almost always fatal.

Trismus nascentium is a type of tetanus. Babies can get it if their mothers are not immune. Today, it is rare in developed countries. It mostly happens in places with poor health care. In the 19th century, its cause was unknown. Many enslaved African children got this disease. Medical historians believe that poor living conditions in slave quarters caused it. Sims himself suggested that cleanliness and living conditions played a role.

Using Enslaved People for Medical Research

Using enslaved people for medical research was not seen as wrong in the Antebellum South (the time before the Civil War). For example, the Medical University of South Carolina advertised that it had many "subjects" from the Black population. This meant students could learn anatomy without upsetting anyone.

The college even offered to treat "interesting cases" of enslaved or free Black people for free. They did this for the "benefit" and "instruction" of their students. Their goal was to help medical education.

Founding the First Woman's Hospital in New York

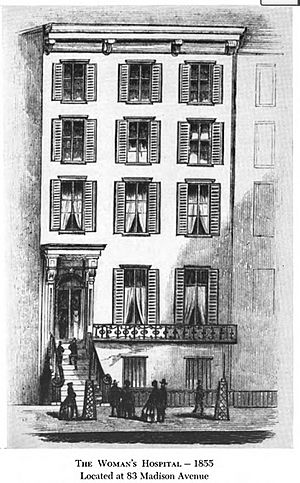

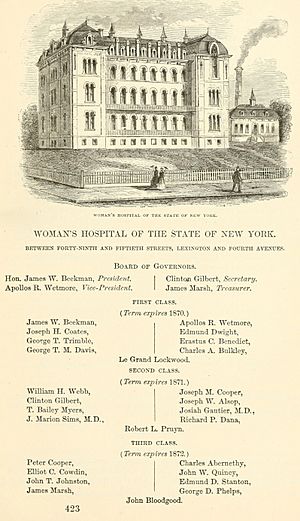

Sims moved to New York in 1853 because of his health. He decided to focus on women's diseases. By 1860, he was very successful.

In 1855, he founded the Woman's Hospital. This was the first hospital in the United States specifically for women. Its main goal was to fix fistulas using Sims' methods for poor women. The hospital quickly filled its 30 beds. Sims often operated without help from other doctors.

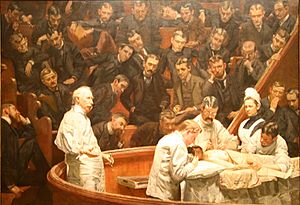

The New York medical community did not support his project at first. They called him a "quack" and said the hospital was a "fraud." But the hospital continued its work. Sims often performed operations in an operating theater. This allowed medical students and other doctors to watch and learn.

Sims and the Civil War

Sims supported the Southern states. Many of his patients in New York were Southern women. As the American Civil War approached, his practice suffered. He did not feel comfortable staying in New York.

In 1861, Sims, who saw himself as a "loyal Southerner," moved to Europe. He visited hospitals and treated fistula patients in London, Paris, and other cities. He also had consulting rooms in Paris, Berlin, and London.

Some sources suggest he was secretly working for the Confederacy. He was trying to get money, recognition, and supplies for them. U.S. diplomats in Europe believed he was a spy.

One famous story is that Sims was called to treat Empress Eugénie for a fistula in 1863. This helped his worldwide fame. However, some historians say Eugénie might not have been sick at all. They believe Sims' visits were secret meetings for the Confederacy.

Sims stayed in Europe until 1865, near the end of the Civil War. He later said that giving Black people the right to vote was a "dreadful mistake." But he also said the South should accept its loss and move forward.

Later Career and Contributions

After treating royalty in Europe, Sims raised his fees. He mostly treated wealthy women, but he still had many charity patients. He became known for the Battey surgery, which involved removing both ovaries. This was a popular treatment for mental illness and other "nerve disorders" at the time. These problems were then thought to be caused by female reproductive issues.

Sims received many honors and medals for his successful operations. Today, the need for many of these surgeries is questioned. He performed surgeries for what were considered gynecological problems. These were often done at the request of the women's husbands or fathers. At that time, they could force women into surgery.

Under the support of Napoleon III, Sims helped organize the American-Anglo Ambulance Corps. This group treated wounded soldiers from both sides during the Battle of Sedan.

Advocating for Cancer Care

In 1871, Sims returned to New York. He continued working at the Woman's Hospital. He provided surgical treatment for women with cancer. At the time, cancer was a feared disease. Many thought it was contagious. The Ladies' Board of the Woman's Hospital did not want cancer patients admitted.

Sims argued strongly for treating cancer patients. He also criticized limits on how many doctors could watch operations. He believed this stopped the spread of medical knowledge. Because of this disagreement, Sims resigned from the hospital in 1874.

After leaving the Woman's Hospital, Sims helped establish America's first cancer institute, the New York Cancer Hospital. In 1876, he was elected president of the American Medical Association.

Death

Sims had two heart attacks in 1877. In 1880, he got a severe case of typhoid fever. He recovered in June 1881 and traveled to France. After returning to the U.S. in September 1881, he had more heart problems.

Sims died of a heart attack on November 13, 1883, in New York City (Manhattan). He is buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Legacy and Honors

Sims received many honors during his life. He was a member of many medical societies. He received awards from France, Belgium, Germany, and other countries.

A bronze statue of Sims was put up in Bryant Park, New York, in 1894. It was later moved to Central Park in 1934. In 2018, the statue was voted to be removed from Central Park. It is planned to be moved to Green-Wood Cemetery, where Sims is buried.

There are other statues of Sims. One is at his old school, Jefferson Medical College. Another is at the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama. A statue of Sims is also at the South Carolina State House in Columbia, South Carolina. Some people have called for these statues to be removed.

A painting called Medical Giants of Alabama showed Sims and other white men with a partially clothed Black patient. It was removed from the University of Alabama at Birmingham in 2005 or 2006 due to complaints.

The Medical University of South Carolina renamed a special position that was in his honor. The medical college at the University of South Carolina is named Sims College. In 2020, the university asked the state to rename the college.

A J. Marion Sims Foundation was started in his hometown of Lancaster, South Carolina, in 1995. It has given out almost $50,000,000 in grants. The Marion Sims Memorial Hospital is also in Lancaster. In Montgomery, Alabama, a historical marker shows where Sims' house and hospital were located. In 1953, Sims was elected to the Alabama Hall of Fame.

In 2018, a play called Behind the Sheet was performed in New York. It was about a fictional enslaved woman named Philomena who helps Sims with his research.

Key Contributions to Medicine

- Fistula Repair: Sims developed a way to fix fistulas. He also invented the use of silver wire for sutures.

- Medical Tools: He invented the Sims' speculum (a tool for medical exams) and the Sims' sigmoid catheter. There is a movement to remove his name from these tools.

- Patient Positioning: He created the Sims' position, a way to position patients for exams and surgery.

- Fertility Treatment: He worked on Insemination and the postcoital test for fertility.

- Cancer Care: Sims strongly supported letting cancer patients into hospitals. This was at a time when many feared cancer was contagious.

- Abdominal Surgery: He suggested a laparotomy (a cut into the abdomen) to stop bleeding from bullet wounds. This idea later became accepted.

- Gallbladder Surgery: In 1878, Sims drained a swollen gallbladder and removed its stones.

Archival Materials

Papers belonging to Dr. Sims, about 150 items, are kept at the Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Some of these are available online. A few letters are also in the libraries of the Medical University of South Carolina and Duke University.

See also

- Unethical human experimentation in the United States

- Anarcha Westcott

- Mothers of Gynecology Movement

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |