James Bradley (former slave) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Bradley

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1810 Guinea, Africa

|

| Died | Known to be alive in 1837. |

| Occupation | Freedman (former slave); planned to study for ministry |

| Years active | 1833—1837 |

| Known for | Participating in Lane Seminary's 1834 debates on slavery |

James Bradley (born around 1810 – after 1837) was an African man who was enslaved in the United States. He managed to buy his freedom and became an important activist against slavery in Ohio.

James was only two or three years old when he was captured in Africa and brought to the United States. He was bought by a man named Mr. Bradley in Pendleton County, Kentucky. Later, he moved with the Bradley family to the Arkansas Territory. Even though he worked all day as a slave, James also worked for himself at night. In 1833, after eight years of hard work, he finally bought his freedom. He then moved to Cincinnati, which was in the free state of Ohio.

Bradley became involved with Lane Seminary and played a key role in the Lane Debates on Slavery in 1834. His powerful speech inspired students to create educational programs for Black people and to connect with the community. However, the Seminary's leaders stopped these anti-slavery activities. This led to about forty students, known as the Lane Rebels, leaving the school. They moved to Oberlin, Ohio, which then became a diverse community and a center for fighting against slavery. James Bradley moved to Oberlin with the other Rebels. He studied for a year at the Sheffield Manual Labor Institute, a school connected to Oberlin College.

Bradley wrote his own story, which tells us a lot about his time as a slave and how he gained freedom. We don't know what happened to him after 1837, and there are no pictures or descriptions of him.

Contents

James Bradley's Life as a Slave

Early Childhood

James Bradley was born in Guinea, a region in West Africa. When he was just two or three years old, he was captured and taken from his family. He later said that "soul-destroyers tore me from my mother's arms." He was forced to travel a long way over land before being put on a ship to America. The ship was full of chained adult African men and women. But because James was so small, he was allowed to move freely on the ship's deck. He was brought to America illegally, as the legal import of slaves had ended in 1808.

After arriving in Charleston, South Carolina, James was bought by a slaveholder. He was then taken to Pendleton County, Kentucky, and sold again about six months later to a man named Bradley. James took his last name from this owner. He lived and worked as a slave with Mr. Bradley's family in Pendleton County.

Bradley wrote that his owner was thought to be a kind master because James wasn't often beaten and had enough food. However, James also said that he was sometimes kicked and thrown around when he was very young. When he was nine, he was hit so hard that he passed out, and his owner thought he had died. At fifteen, he became very sick from overwork, which made his owner angry. The Bradley children also sometimes made threatening gestures with knives and axes. James worked extremely hard, from sunrise until dark. By the time he was fourteen, he constantly thought about how to become free.

He taught himself to read simple words and spell using a spelling book he kept in his hat. He even convinced one of his owner's sons to teach him to write. But his mistress found out on the second night. She scolded her son, saying that if James could write, he could write a pass to escape. After that, James practiced writing on his own.

My master had kept me ignorant of everything he could. I was never told anything about God, or my own soul... [H]ow I longed to be able to read the Bible!

Shortly after he turned fifteen, James moved with the Bradley family to Arkansas. They lived near the Choctaw mission and Fort Towson, in what is now Oklahoma. After Mr. Bradley died, his widow put young James in charge of running her plantation.

Planning to Buy Freedom

James learned that he should never show any desire for freedom, because it would lead to worse treatment. But gaining freedom was a very strong wish for him.

How strange it is that anybody should believe any human being could be a slave, and yet be contented! I do not believe that there ever was a slave, who did not long for liberty. I know very well that slave-owners take a great deal of pains to make the people in the free states believe that the slaves are happy; but I know, likewise, that I was never acquainted with a slave, however well he was treated, who did not long to be free. There is one thing about this, that people in the free states do not understand. When they ask slaves whether they wish for liberty, they answer, "No"; and very likely they will go as far as to say they would not leave their masters for the world. But at the same time, they desire liberty more than anything else, and have, perhaps all along been laying plans to get free. The truth is, if a slave shows any discontent, he is sure to be treated worse, and worked harder for it; and every slave knows this. This is why they are careful not to show any uneasiness when white men ask them about freedom. When they are alone by themselves, all their talk is about liberty – liberty! It is the great thought and feeling that fills the minds full all the time.

James came up with a plan to buy his freedom. He worked all day for his owner, then slept for a few hours. After that, while others slept, he worked for himself to earn money. He started by weaving collars for horses from corn husks. He found a way to work enough at night without being too tired for his day work. After eight years, in 1833, he was able to buy his freedom for $700 (which would be worth a lot more today). He also had another $200 to start his new life.

After toiling all day for my mistress, I used to sleep three or four hours, and then get up and work for myself the remainder of the night. I made collars for horses out of plaited husks. I could weave one in about eight hours; and generally I took time enough from my sleep to make two collars in the course of a week. I sold them for fifty cents each...

With my first money I bought a pig. The next year I earned for myself about thirteen dollars; and the next about thirty. There was a good deal of wild land in the neighborhood, that belonged to Congress. I used to go out with my hoe, and dig up little patches, which I planted with corn, and got up in the night to tend it. My hogs were fattened with this corn, and I used to sell a number each year. Besides this, I used to raise small patches of tobacco, and sell it to buy more corn for my pigs. In this way I worked for five years; at the end of which time, after taking out my losses, I found that I had earned one hundred and sixty dollars.

With this money I hired my own time for two years. During this period, I worked almost all the time, night and day. The hope of liberty stung my nerves, and braced up my soul so much, that I could do with very little sleep or rest. I could do a great deal more work than I was ever able to do before. At the end of the two years, I had earned three hundred dollars, besides feeding and clothing myself. I now bought my time for eighteen months longer, and went two hundred and fifty miles west, nearly into Texas, where I could make more money. Here I earned enough to buy myself, which I did in 1833, about one year ago. I paid for myself, including what I gave for my time, about seven hundred dollars.

Freedom and Education

Journey to Freedom

Once he was free, James headed for a free state. He spent some time in Northern Kentucky before going to Covington, Kentucky. From there, he crossed the Ohio River, which was the dividing line between slave states and free states. He arrived in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Lane Seminary

James wanted to become a minister. He was accepted into Lane Seminary on May 28, 1833. He was the first African-American student there. He said that he was treated kindly by the other students, no matter his skin color. Lyman Beecher, the president of Lane, told students to be careful how they acted around Black people. Some students did not believe in ending slavery. So, when Beecher invited students to his home, Bradley felt it was better not to go. Beecher thought Bradley was just shy.

When I arrived in Cincinnati, I heard of Lane Seminary, about two miles out of the city. I had for years been praying to God that my dark mind might see the light of knowledge... But in all respects I am treated just as kindly, and as much like a brother by the students, as if my skin were as white, and my education as good as their own. Thanks to the Lord, prejudice against color does not exist in Lane Seminary! If my life is spared, I shall probably spend several years here, and prepare to preach the gospel.

While at Lane, Bradley helped coordinate efforts to rescue slaves seeking freedom through the Underground Railroad. He helped them cross the Ohio River and travel towards Ontario, Canada. In 1834, his personal story was published in a book called The Oasis.

Lane Seminary Debates

In the early 1830s, there were two main ideas about slavery in America. One idea, supported by the American Colonization Society, was to send free Black people to colonies in Africa, like Liberia. They believed white and Black people could not live together equally. The other idea, supported by abolitionists, was that slavery was morally wrong and should be ended immediately.

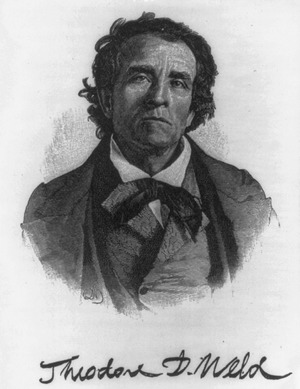

Theodore Dwight Weld, a strong abolitionist, led important debates at Lane Seminary in 1834. He helped students prepare powerful speeches. The debates were about whether slavery should be ended right away (abolition) or if enslaved people should be sent to Africa (colonization). Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose father was the president of Lane, was among those who attended.

James Bradley, who supported ending slavery, spoke in these debates. He was the only Black person to speak. Some Southern students had brought their enslaved people to the debates, but none of them were asked to speak. It was remarkable that James not only spoke but that people listened to him. He shared what it was like to be enslaved. He made the audience emotional when he described being on the slave ship. He emphasized that everyone needed equality, education, and freedom.

Bradley's classmate, Henry Brewster Stanton, said that Bradley clearly and thoughtfully answered all the arguments against ending slavery immediately. These arguments included fears that it would be unsafe or that freed Black people couldn't take care of themselves. Bradley even used humor in his speech. Both abolitionists and those who supported colonization listened closely, and the audience often laughed. He made it clear that enslaved people deeply desired freedom and education, and wanted to care for themselves and others. Many people felt his speech was the most important of the debates.

By the end of the debates, many students strongly opposed slavery. They voted to support an immediate end to slavery. The Colonization Society was voted out. Some students formed an anti-slavery group. They started a library, held Bible classes, and opened free schools in Black neighborhoods. These classes became so popular that they had to turn students away. At that time, one-third of Ohio's Black population lived in Cincinnati. Bradley became a leader in the new student anti-slavery society.

However, local leaders and most of the seminary's trustees were worried about their businesses, as many had clients in the South. They complained to Lane Seminary while President Beecher was away. The Board of Trustees stopped all anti-slavery activities, criticized the debates, and banned any discussion of slavery. This caused many students, especially those connected to Weld, to leave the school. They went to Oberlin College, which then became a diverse school and a leader in the abolitionist movement.

Sheffield Manual Labor Institute

Bradley joined the other Lane Rebels and moved to Oberlin Collegiate Institute (now Oberlin College) in 1835. In 1836, he enrolled in a school Oberlin set up for the many new students: the Sheffield Manual Labor Institute. This school was in Sheffield, Ohio, about 17 miles northeast of Oberlin. Sheffield offered high school-level classes combined with manual labor. The school closed after a year, partly because it refused to be segregated, which was required by a new Ohio law.

Sadly, we don't know anything about James Bradley's life after 1837. The last mention of him is in a letter from another Lane Rebel, C. Stewart Renshaw, who called him "our dear brother." He might be the "negro, late of Sheffield College," who helped free fourteen enslaved people from one plantation.

James Bradley's Legacy

Bradley's speech showed how powerful it is when people directly affected by an issue speak about their experiences and desires. Often, only people with power, like those with education or wealth, speak about social problems. Bradley proved that those directly involved should always be part of the conversation.

The debates at Lane Seminary, especially because of Bradley's effective speaking, gave a strong voice to the anti-slavery movement. When Weld and about 40 other Lane Rebels moved to Oberlin, the college became a leader in the fight against slavery. Students at other colleges also started discussions about free speech on their campuses.

Statue and Plaque

In 1988, a statue of James Bradley was put up in Covington, Kentucky. It is near the spot where Bradley crossed the Ohio River into Cincinnati. The statue, made by George Danhires, shows Bradley sitting on a riverfront bench, looking north across the Ohio River towards Cincinnati, while reading a book. In 2014, it was voted one of the top five interesting statues in the greater Cincinnati area. The statue was restored in 2016.

Media Portrayal

James Bradley appears as a character in the 2019 movie Sons & Daughters of Thunder. This movie is about the Lane Debates and is based on a play by Earlene Hawley and Curtis Heeter.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |