Jean-Martin Charcot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-Martin Charcot

|

|

|---|---|

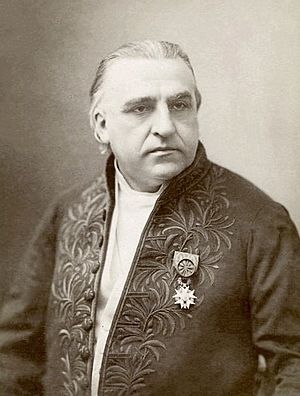

Wearing Legion of Honour Officier,

with rosette |

|

| Born | 29 November 1825 |

| Died | 16 August 1893 (aged 67) Lac des Settons, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Studying and discovering neurological diseases |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neurologist and professor of anatomical pathology |

| Institutions | Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital |

Jean-Martin Charcot (born November 29, 1825 – died August 16, 1893) was a famous French neurologist. A neurologist is a doctor who studies and treats problems with the brain, spinal cord, and nerves. Charcot was also a professor who taught about diseases of the body's tissues.

He is known as "the founder of modern neurology" because of his important work. He studied conditions like hypnosis and hysteria. His name is linked to at least 15 medical terms, including several conditions sometimes called Charcot diseases. Many people call him "the father of French neurology." His work greatly helped the fields of neurology and psychology grow.

Contents

His Life

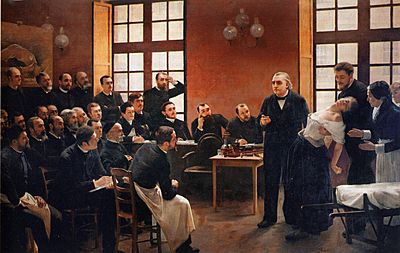

Jean-Martin Charcot was born in Paris, France. He worked and taught for 33 years at the famous Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital. He was such a good teacher that students came from all over Europe to learn from him. In 1882, he started a special clinic for neurology at Salpêtrière. This was the first clinic of its kind in Europe.

In 1864, he married a wealthy widow named Madame Durvis. They had two children, Jeanne and Jean-Baptiste. Jean-Baptiste later became a doctor and a famous explorer of the polar regions.

His Work

Studying the Nervous System

Charcot mostly focused on studying the nervous system. He was the first to describe and name a disease called multiple sclerosis. He looked at earlier reports and added his own observations. He called the disease sclérose en plaques.

He also described three signs of multiple sclerosis, now known as Charcot's triad 1. These are nystagmus (uncontrolled eye movements), intention tremor (shaking when trying to do something), and telegraphic speech (speaking in short, choppy sentences). Charcot also noticed that patients had problems with memory and thinking.

He was also the first to describe a condition called Charcot joint. This is when joint surfaces break down because of a loss of feeling in the joint. He also studied how different parts of the brain work. He looked at the role of arteries in cerebral hemorrhage, which is bleeding in the brain.

Charcot was one of the first to describe Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT). This disease affects the nerves in the arms and legs. He announced this discovery at the same time as Pierre Marie from France and Howard Henry Tooth from England.

His studies between 1868 and 1881 greatly improved our understanding of Parkinson's disease. He helped tell the difference between stiffness, weakness, and slow movement in patients. He also suggested that the disease, once called paralysis agitans (shaking palsy), be renamed after James Parkinson. In 1882, Charcot received the first European professional position for studying nervous system diseases.

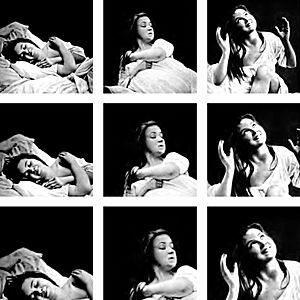

Hypnosis and Hysteria

Charcot is very well known for his work on hypnosis and hysteria. He worked with patients like Louise Augustine Gleizes and Marie "Blanche" Wittmann, who was called the "Queen of Hysterics."

At first, he thought hysteria was a problem with the nervous system that people inherited. But later in his life, he believed it was a psychological disease. He strongly argued that hysteria could affect men too, not just women. He showed many cases of male hysteria caused by injuries. Charcot's ideas helped doctors understand how physical injuries could lead to nervous system problems.

Art and Medicine

Charcot believed that art was a very important tool for understanding diseases. He used photos and drawings in his classes and talks. Many of these were made by him or his students. He also drew as a hobby. He is considered a key person in using photography to study nervous system conditions.

Misunderstandings About Charcot

Some people have had wrong ideas about Charcot, thinking he was harsh or bossy. These ideas often came from a fictional book called The Story of San Michele (1929) by Axel Munthe. Munthe claimed to be Charcot's assistant, but he was actually just one of many medical students. Munthe had a disagreement with Charcot, which led to him being banned from the hospital wards.

His Impact

One of Charcot's biggest impacts was his help in developing a careful way to examine the nervous system. He connected specific signs of illness with problems found in the body after death. He did this by studying patients for a long time and then examining their bodies closely. This led to clear descriptions of many nervous system diseases, like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Charcot is also famous for influencing many doctors who studied with him. These include Sigmund Freud, Joseph Babinski, Pierre Janet, William James, and Georges Gilles de la Tourette. Charcot even named Tourette syndrome after his student, Georges Gilles de la Tourette.

After Charcot's death, ideas about hysteria changed. Some people thought it was no longer a real neurological condition. However, Charcot's work still had a "prominent" place in French psychiatry and psychology. His work on hysteria and hypnotism was different from Sigmund Freud's later ideas. Charcot believed that neurological problems were the cause.

The Charcot-Janet school, formed by Charcot and his student Janet, greatly helped our understanding of multiple personality disorders.

Diseases Named After Him

An eponym is when something is named after a person. Charcot's name is linked to many diseases and conditions, including:

- Charcot's artery (a small artery in the brain)

- Charcot's joint (joint damage, often seen in people with diabetes)

- Charcot's disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease)

- Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (a nerve disorder affecting muscles)

- Charcot–Wilbrand syndrome (problems recognizing objects visually)

- Charcot's intermittent hepatic fever (a type of fever with pain and jaundice)

- Charcot–Bouchard aneurysms (tiny weak spots in brain arteries)

- Charcot's triad of acute cholangitis (three signs of a bile duct infection)

- Charcot's neurologic triad of multiple sclerosis (three signs of multiple sclerosis)

- Charcot–Leyden crystals (crystals found in allergic diseases)

His name is also linked to a type of high-pressure shower.

Interesting Facts About Jean-Martin Charcot

- On April 22, 1858, Charcot was made a Knight of France's Legion of Honour. He was later promoted to Officer and then Commander.

- A collection of Charcot's letters is kept at the United States National Library of Medicine.

- Charcot Island in Antarctica was discovered by his son, Jean-Baptiste Charcot. He named the island to honor his father.

- The Charcot Award is given every two years. It honors outstanding research into understanding or treating multiple sclerosis.

See also

In Spanish: Jean-Martin Charcot para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Martin Charcot para niños