Jean Price-Mars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

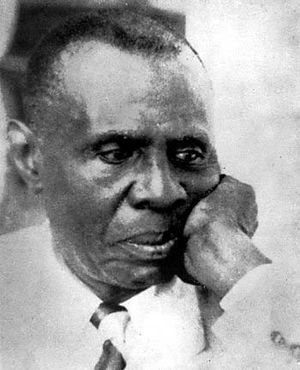

Jean Price-Mars

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Minister of Foreign Affairs and Worship | |

| In office 14 December 1956 – 9 February 1957 |

|

| President | Joseph Nemours Pierre-Louis |

| Preceded by | Joseph D. Charles |

| Succeeded by | Evremont Carrié |

| Minister for Foreign Affairs, Worship and Education | |

| In office 19 August 1946 – 10 April 1947 |

|

| President | Dumarsais Estimé |

| Preceded by | Antoine Levelt (Foreign Affairs and Worship) Daniel Fignolé (Education) |

| Succeeded by | Edmée Manigat (Foreign Affairs and Worship) Emile Saint-Lot (Education) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 15, 1876 Grande-Rivière-du-Nord |

| Died | March 1, 1969 (aged 92) Pétion-Ville |

Jean Price-Mars (born October 15, 1876 – died March 1, 1969) was an important Haitian person. He was many things: a doctor, a teacher, a politician, a diplomat, a writer, and someone who studied cultures (an ethnographer).

Price-Mars worked for Haiti in different countries. He was a secretary for the Haitian group in Washington, D.C. in 1909. Later, he was a temporary ambassador in Paris from 1915 to 1917. This was during the time when the United States first occupied Haiti.

In 1922, Price-Mars finished his medical studies. He had stopped them earlier because he didn't have a scholarship.

In 1930, Price-Mars decided not to run for president of Haiti. He supported Stenio Vincent instead. But then, Price-Mars led the Senate's opposition against the new president. Because of this, he was forced out of politics for a while.

In 1941, Price-Mars was elected to the Senate again. He became the secretary of state for foreign relations in 1946. Later, he served as an ambassador to the Dominican Republic. Even when he was in his eighties, he continued to serve Haiti. He was an ambassador at the United Nations and also an ambassador to France.

What was the Négritude Movement?

Price-Mars strongly supported the Négritude movement in Haiti through his writing. This movement was about "discovering" and celebrating the African roots of Haitian society. Price-Mars was the first important person to defend Vodou. He said it was a complete religion with gods, priests, beliefs, and rules for good behavior.

He spoke out against the common idea that European cultures were better. This idea came from the colonial period. He also rejected parts of non-white, non-Western cultures in the Americas. His love for his country meant he embraced Haiti's cultural identity as African, which came from slavery.

Price-Mars's ideas were inspired by how Haitian farmers bravely resisted the United States occupation from 1915 to 1934. He was sad that the rich and powerful people in Haiti had forgotten the traditions that led to Haiti's independence from French colonialism. But he was proud of how the poor people behaved. He criticized the elite for not being able to help the Haitian people improve their lives.

What is Collective Bovarysme?

Price-Mars created the term collective bovarysme. He used it to describe how the elite (rich and powerful people) in Haiti identified with their part-European background. At the same time, they denied their African heritage. This idea comes from a novel called Madame Bovary. In the book, the main character, Emma Bovary, wants to escape her social life, which she doesn't like.

Price-Mars noticed that the elite were mostly people of mixed ancestry. They were descendants of former free persons of color and focused on their "whiteness." Most Haitians, however, had more African ancestors. His dislike for the elite went beyond their "bovarysme" about race.

He believed the elite had too much economic and political power. He understood that their power came from taxing crops, especially coffee. Coffee was the main export, grown by the farmers who had defended the country when the elite had left to protect their own interests.

He also criticized the elite's role in Haitian education. The elite thought they needed to "civilize" the common people. Price-Mars wrote often about education programs. He looked at the "intellectual tools" available in Haiti. He challenged the elite to help the common people make progress because the elite had advantages.

He eventually came to believe that Haiti's history of slavery was the true source of Haitian identity and culture. He admired the culture and religion that developed among the enslaved people. He saw this as their foundation for fighting against the Europeans and building the Haitian nation.

The term collective bovarysme was also used to describe Dominicans who were mostly Black but denied their African roots. Instead, they favored their Spanish ancestry. During the Dominican War of Independence, many Dominicans who wanted independence did not see themselves as Black. They saw the conflict as a war between white people and Black people, or between "civilized" and "barbaric" people.

Notable Works

- La Vocation de l'elite (1919)

- Ainsi parla l'oncle (1928) Translated: So Spoke the Uncle (1983)

- La République d'Haïti et la République Dominicaine (1953)

- De Saint-Domingue à Haïti (1957)

See also

In Spanish: Jean Price-Mars para niños

In Spanish: Jean Price-Mars para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |