Jin–Song wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Jin–Song Wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jin dynasty (blue) and Song dynasty (orange) in 1141 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Jin puppet states

Co-belligerents Western Xia (1225–27)

Eastern Xia (1233) |

Song dynasty Co-belligerents Khitans

Mongol Empire (1211–33)

|

||||||

| Jin–Song wars | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 宋金戰爭 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 宋金战争 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

The Jin–Song Wars were a long series of fights between two powerful empires in China: the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and the Han Chinese-led Song dynasty. These wars lasted for over 100 years, from 1125 to 1234.

The Jurchens were a group of tribes who lived in what is now Northeast China. In 1115, they rebelled against their rulers, the Khitan-led Liao dynasty. The Jin and Song dynasties decided to team up against their common enemy, the Liao. The Jin promised to give the Song some land back if they won. However, the Jin defeated the Liao very quickly, and the Song army didn't do so well. This made the Jin unwilling to give up the land they had promised.

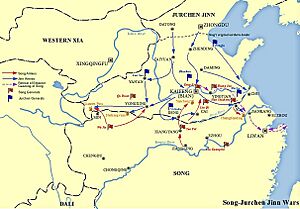

After some difficult talks, the Jurchens attacked the Song in 1125. They sent two armies: one towards Taiyuan and another towards Bianjing (which is now Kaifeng), the Song capital city. This surprise attack led to big changes in China, including the Song court moving south and the start of the Southern Song dynasty.

Contents

- How the Jin and Song Became Enemies

- War Against the Northern Song Dynasty

- Wars with the Southern Song Dynasty

- What Changed Because of the Wars

- See also

How the Jin and Song Became Enemies

The Jurchens Rise to Power

The Jurchens were tribes who spoke a language called Tungusic. They lived in Northeast Asia, in areas that are now part of China. Many Jurchen tribes were under the control of the Liao dynasty. The Liao empire was ruled by the nomadic Khitans and covered a large part of modern Mongolia, northern China, and parts of Korea and Russia. South of the Liao was the Song dynasty, ruled by the Han Chinese.

The Song and Liao dynasties had been peaceful for a long time. However, after a military defeat in 1005, the Song had to pay the Liao a large amount of silk and silver every year.

In 1114, a leader named Wanyan Aguda united the Jurchen tribes. He led a rebellion against the Liao and, in 1115, he declared himself emperor of the new "golden" Jin dynasty.

The Song and Jin Alliance Against Liao

When the Song emperor Huizong heard about the Jurchen uprising, he saw a chance to get back some land called the Sixteen Prefectures. This land had been taken by the Liao dynasty in 938. The Song had tried many times to get it back but failed. So, the Song decided to team up with the Jin against their shared enemy, the Liao.

Since the Liao controlled the land routes, the Song and Jin had to send messages by sea. They started secret talks in 1118. At first, they agreed that each side would keep any Liao land they captured. But in 1120, Aguda agreed to give the Sixteen Prefectures to the Song. In return, the Song would send their yearly payments, which used to go to the Liao, to the Jin instead.

However, the Jurchens quickly captured the Liao's main capital. This made them change their minds. They only offered the Song parts of the Sixteen Prefectures. They decided the Jin would attack the Liao Central Capital, and the Song would attack the Liao Southern Capital, Yanjing (modern Beijing).

Problems with the Alliance

The joint attack was planned for 1121 but was moved to 1122. On February 23, 1122, the Jin captured the Liao Central Capital as planned. But the Song delayed their part of the attack. They were busy fighting another group called the Western Xia and putting down a rebellion led by Fang La.

When the Song army finally attacked Yanjing in May 1122, the weaker Liao forces easily pushed them back. Another attack failed later that year. Both times, the Song general Tong Guan had to retreat. After the first failed attack, Aguda changed the deal again. He only promised Yanjing and six other areas to the Song. In early 1123, the Jurchen forces easily took the Liao Southern Capital themselves. They looted the city and took its people as slaves.

The quick collapse of the Liao dynasty led to more talks between the Song and Jin. The Jin's military success gave them more power in these talks. Aguda became frustrated because the Song still wanted most of the land, even though their army had failed. In spring 1123, they finally agreed on a treaty. Only seven areas, including Yanjing, would be returned to the Song. The Song would also pay a large yearly payment of silk and silver to the Jin, plus a one-time payment of copper coins. In May 1123, the Song armies entered the looted Yanjing.

War Against the Northern Song Dynasty

The Alliance Breaks Down

Just one month after the Song got Yanjing back, a former Liao official named Zhang Jue killed the main Jin official in Pingzhou and gave the city to the Song. The Jurchens defeated Zhang's armies a few months later, and Zhang fled to Yanjing. Even though the Song agreed to execute Zhang in late 1123, this event caused tension. The 1123 treaty had said that neither side should protect defectors.

In 1124, Song officials angered the Jin even more by asking for nine more border areas. The new Jin emperor Taizong, Aguda's brother, was unsure. But his warrior princes, Wanyan Zonghan and Wanyan Zongwang, strongly refused to give up any more land. Taizong eventually gave two areas, but by then, the Jin leaders were ready to attack the Song.

Before invading the Song, the Jurchens made peace with their western neighbors, the Tangut Western Xia, in 1124. The next year, they captured Tianzuo, the last Liao emperor, ending the Liao dynasty for good. With the Liao gone, the Jurchens were ready to end their alliance with the Song and prepare for an invasion.

The First Jin Invasion

In November 1125, Emperor Taizong ordered his armies to attack the Song. Zhang Jue's defection two years earlier was used as the reason for the war. Two armies were sent to capture important Song cities.

The Siege of Taiyuan

The western Jin army, led by Wanyan Zonghan, marched from Datong towards Taiyuan. Taiyuan was in the mountains of Shanxi, on the way to the Song western capital, Luoyang. The Song forces were not ready for an invasion and were surprised.

The Song general Tong Guan heard about the attack from a messenger he had sent to the Jin. The messenger reported that the Jurchens would stop the invasion if the Song gave them control of Hebei and Shanxi. Tong Guan retreated from Taiyuan, leaving his troops to Wang Bing. The Jin armies surrounded Taiyuan in mid-January 1126. Under Wang Bing's command, Taiyuan held out long enough to stop the Jurchen troops from reaching Luoyang.

The First Siege of Kaifeng

Meanwhile, the eastern Jin army, led by Wanyan Zongwang, marched towards Yanjing (modern Beijing) and then to the Song capital, Kaifeng. This army didn't face much resistance. Zongwang easily took Yanjing, where a Song general named Guo Yaoshi switched sides to the Jin. When the Song had tried to reclaim the Sixteen Prefectures, the local Chinese people had fought them fiercely. But when the Jurchens invaded, the Chinese people didn't resist at all. By the end of December 1125, the Jin army controlled two prefectures and had taken back the Sixteen Prefectures. The eastern army was close to Kaifeng by early 1126.

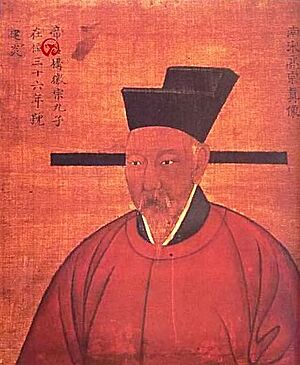

Fearing the Jin army, Song emperor Huizong planned to flee south. But leaving the capital would look like giving up. So, court officials convinced him to step down as emperor. In January 1126, just before the Chinese New Year, Huizong gave his throne to his son, Qinzong. Huizong became a "Retired Emperor."

The Jurchen forces reached the Yellow River on January 27, 1126. Huizong fled Kaifeng the next day, escaping south and leaving Emperor Qinzong in charge.

Kaifeng was surrounded on January 31, 1126. The Jin army commander promised to spare the city if the Song agreed to:

- Become a Jin vassal (meaning they would be under Jin control).

- Give up the prime minister and an imperial prince as prisoners.

- Give up three Chinese prefectures: Hejian, Taiyuan, and Zhongshan.

- Pay a huge amount of silver, gold, silk, satin, horses, mules, cattle, and camels. This payment was worth about 180 years of the yearly payments the Song had been giving the Jin since 1123!

With little hope of help, arguments broke out in the Song court. Some officials supported the Jin offer, while others, like Li Gang, wanted to keep fighting until reinforcements arrived. A night attack against the Jin failed, and the peace-supporters took over. The failed attack pushed Qinzong to agree to the Jin's demands. The Song recognized Jin control over the three prefectures. The Jin army ended the siege in March after 33 days.

The Second Jin Invasion

Almost as soon as the Jin armies left Kaifeng, Emperor Qinzong broke the deal. He sent two armies to fight the Jurchen troops attacking Taiyuan and to strengthen the defenses of Zhongshan and Hejian. But an army of 90,000 soldiers and another of 60,000 were defeated by Jin forces by June. A second attempt to rescue Taiyuan also failed.

The Jin accused the Song of breaking the agreement and realized how weak the Song were. So, the Jin generals launched a second attack, again dividing their troops into two armies. Wanyan Zonghan, who had left Taiyuan after the Kaifeng agreement, returned with his western army. Taiyuan was overwhelmed and fell in September 1126, after being under siege for 260 days.

When the Song court heard about Taiyuan's fall, the officials who wanted to fight were again replaced by those who favored peace. In mid-December, the two Jurchen armies met at Kaifeng for the second time that year.

The Second Siege of Kaifeng

After several Song armies were defeated in the north, Emperor Qinzong wanted to make peace with the Jin. But he made a huge mistake: he ordered his remaining armies to protect other cities instead of Kaifeng. He left Kaifeng with fewer than 100,000 soldiers. The Song forces were spread out, unable to stop the second Jin siege of the capital.

The Jin attack began in mid-December 1126. Even as fighting continued, Qinzong kept asking for peace. But the Jin's demands for land were huge: they wanted all provinces north of the Yellow River. After more than twenty days of heavy fighting, the Song defenses were destroyed, and the soldiers' spirits dropped. On January 9, 1127, the Jurchens broke through and began to loot the city.

Emperor Qinzong tried to calm the victors by offering all the remaining wealth of the capital. The royal treasury was emptied, and the belongings of the city's people were taken. The Song emperor surrendered completely a few days later.

Qinzong, the former emperor Huizong, and many members of the Song royal family and high officials were captured by the Jurchens. They were taken north to Huining (modern Harbin). There, they lost their royal status and became common people. The former emperors were treated very badly by their captors. However, the harsh treatment of the Song royalty became softer after Huizong died in 1135. Titles were given to the dead emperor, and his son Qinzong was made a Duke, a position with a salary.

Why the Song Failed

Many things led to the Song's repeated military mistakes and the loss of northern China to the Jurchens. Some historical accounts say that Emperor Huizong's court was corrupt and responsible for the dynasty's decline. These stories blamed Huizong and his officials for their moral failures.

Emperor Huizong was more skilled as a painter than as a ruler. He was known for spending too much money on building gardens and temples, even while rebellions threatened the state.

A modern historian, Ari Daniel Levine, suggests that problems in the military and government leadership were more to blame. The loss of northern China was not meant to happen. The government used its military too much and was too confident in its own strength. Huizong used state money for failed wars against the Western Xia. The Song's insistence on getting more Liao land only made their Jin allies angry. Song leaders made diplomatic mistakes, underestimating the Jin and allowing their military power to grow unchecked.

The Song had many resources, except for horses. They managed their resources poorly during battles. Unlike earlier empires like the Han and Tang, the Song didn't have much land in Central Asia where they could breed or get many horses. As Song general Li Gang said, without a steady supply of horses, the dynasty was at a big disadvantage against the Jurchen cavalry: "Jin won only because they used iron-shielded cavalry, while we fought them with foot soldiers. It's only natural that [our soldiers] were scattered."

Wars with the Southern Song Dynasty

The Song Court Moves South

Emperor Gaozong Takes the Throne

The Jin leaders had not planned for the Song dynasty to fall completely. They only wanted to weaken the Song to demand more payments. They were not ready for how big their victory was. The Jurchens were busy making their rule stronger in the areas they had taken from Liao. Instead of continuing their invasion of the Song, they decided to "use Chinese to control the Chinese." The Jin hoped a new Chinese state would manage northern China and collect the yearly payments without needing Jurchen help to stop anti-Jin uprisings.

In 1127, the Jurchens set up a former Song official, Zhang Bangchang, as the puppet emperor of a new dynasty called "Da Chu" (Great Chu). This puppet government did not stop the resistance in northern China. The rebels were angry about the Jurchens' looting, not loyal to the Song court. Many Song commanders in northern China stayed loyal to the Song, and armed volunteers formed groups to fight the Jurchens. This resistance made it hard for the Jin to control the north.

Meanwhile, one Song prince, Zhao Gou, had escaped capture. He was on a diplomatic mission and didn't return to Kaifeng before it fell. The future Emperor Gaozong managed to avoid the Jurchen troops by moving from province to province. The Jurchens tried to trick him into returning to Kaifeng, but they failed. Zhao Gou finally arrived in the Song Southern Capital at Yingtianfu (modern Shangqiu) in early June 1127.

For Gaozong, Yingtianfu was the first of several temporary capitals. The court moved there because of its historical importance to Emperor Taizu of Song, the founder of the dynasty. The city's symbolism was meant to make the new emperor's rule seem more legitimate. Gaozong became emperor there on June 12.

After ruling for barely a month, Zhang Bangchang was convinced by the Song to step down as emperor of Great Chu and recognize the Song imperial family. Li Gang pushed Gaozong to execute Zhang for betraying the Song. The emperor agreed, and Zhang was forced to take his own life. Zhang's death showed that the Song were willing to challenge the Jin, and that the Jin had not yet fully controlled the newly conquered lands. With Chu gone, Kaifeng was back under Song control.

Zong Ze, the Song general who had fortified Kaifeng, begged Gaozong to move the court back to the city. But Gaozong refused and retreated south. This move south marked the end of the Northern Song and the beginning of the Southern Song era in Chinese history.

The Journey South

The Song's decision to get rid of Great Chu and execute Zhang Bangchang angered the Jurchens and broke the treaty they had made. The Jin renewed their attacks on the Song and quickly took back much of northern China. In late 1127, Gaozong moved his court even further south from Yingtianfu to Yangzhou, south of the Huai River and north of the Yangtze River. He traveled by sailing down the Grand Canal. The court stayed in Yangzhou for over a year.

When the Jurchens advanced to the Huai River, the court was partly moved to Hangzhou in 1129. Days later, Gaozong barely escaped on horseback, just hours ahead of the Jin troops. After a coup in Hangzhou almost removed him from power, he moved his capital back north to Jiankang (modern Nanjing) in May 1129. However, one month later, Zong Ze's successor, Du Chong, pulled his forces out of Kaifeng, leaving Jiankang open to attack. The emperor moved back to Hangzhou in September, leaving Jiankang to Du Chong. The Jin eventually captured Kaifeng in early 1130.

From 1127 to 1129, the Song sent thirteen groups to the Jin to discuss peace and to ask for the release of Gaozong's mother and Huizong. But the Jin court ignored them. In December 1129, the Jin started a new military attack, sending two armies across the Huai River. On the western side, an army invaded Jiangxi, where the Song dowager empress lived, and captured Hongzhou (present-day Nanchang). They were ordered to retreat a few months later when the eastern army pulled back.

Meanwhile, on the eastern side, Wuzhu led the main Jin army. He crossed the Yangtze southwest of Jiankang and took that city when Du Chong surrendered. Wuzhu quickly advanced from Jiankang to try and capture Gaozong. The Jin took Hangzhou (January 22, 1130) and then Shaoxing further south (February 4). But general Zhang Jun's battle with Wuzhu near Ningbo gave Gaozong time to escape. By the time Wuzhu continued the chase, the Song court was fleeing on ships to islands off the coast of Zhejiang, and then even further south to Wenzhou.

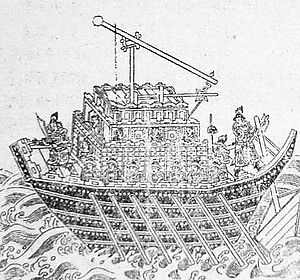

The Jin sent ships to chase Gaozong, but they couldn't catch him. They gave up the chase and the Jurchens retreated north. After they looted the undefended cities of Hangzhou and Suzhou, they finally faced resistance from Song armies led by Yue Fei and Han Shizhong. Han Shizhong even defeated Jurchen forces in a major battle and tried to stop Wuzhu from crossing back to the north bank of the Yangtze. The small boats of the Jin army were no match for Han Shizhong's fleet of seagoing vessels. Wuzhu eventually managed to cross the river by having his troops use incendiary arrows to burn Han's ships. Wuzhu's troops came back south of the Yangtze one last time to Jiankang, which they looted, and then headed north. The Jin had been surprised by the strength of the Song navy, and Wuzhu never tried to cross the Yangtze River again.

In early 1131, Jin armies between the Huai and the Yangtze were pushed back by groups loyal to the Song. Zhang Rong, the leader of these groups, was given a government position for his victory against the Jin.

After the Jin attack that almost captured Gaozong, the emperor ordered Zhang Jun, who was in charge of Shaanxi and Sichuan in the far west, to attack the Jin there. This was meant to reduce pressure on the court. Zhang gathered a large army but was defeated by Wuzhu near Xi'an in late 1130. Wuzhu advanced further west into Gansu. The most important battles between Jin and Song in 1131 and 1132 took place in Shaanxi, Gansu, and Sichuan. The Jin lost two battles at Heshang Yuan in 1131. After failing to enter Sichuan, Wuzhu retreated to Yanjing. He returned to the western front again from 1132 to 1134. The Jin attacked Hubei and Shaanxi in 1132. Wuzhu captured Heshang Yuan in 1133, but his advance was stopped at Xianren Pass. He gave up on taking Sichuan, and no more major battles were fought between the Jin and Song for the rest of the decade.

The Song court returned to Hangzhou in 1133, and the city was renamed Lin'an. The imperial ancestral temple was built in Lin'an later that year, showing that the court had made Lin'an the Song capital, even without a formal announcement. It was still called a temporary capital. Between 1130 and 1137, the court would sometimes move to Jiankang and back to Lin'an. There were ideas to make Jiankang the new capital, but Lin'an won because the court thought it was safer. The natural barriers around Lin'an, like lakes and rice paddies, made it harder for the Jurchen cavalry to break through its defenses. Access to the sea made it easier to escape the city. In 1138, Gaozong officially declared Lin'an the capital, but it was still called a temporary capital. Lin'an remained the capital of the Southern Song for the next 150 years, growing into a major center for business and culture.

The Da Qi Puppet State Attacks the Song

Qin Hui, a Song official, suggested a peaceful solution to the conflict in 1130. He said, "If we want no more conflicts, the southerners need to stay in the south and the northerners in the north." Gaozong, who considered himself a northerner, first rejected this idea. There were attempts at peace in 1132, when the Jin freed a Song diplomat, and in 1133, when the Song offered to become a Jin vassal. But a treaty never happened. The Jin wanted the border to move south from the Huai River to the Yangtze, which was too big a demand for the Song to agree to.

The ongoing resistance from anti-Jin forces in northern China made it hard for the Jurchen campaigns south of the Yangtze. Not wanting the war to drag on, the Jin decided to create Da Qi (the "Great Qi"), their second attempt at a puppet state in northern China. The Jurchens believed that this state, ruled by a Han Chinese person, would attract the loyalty of unhappy rebels. The Jurchens also didn't have enough skilled people, and controlling all of northern China was too difficult to manage.

In late 1129, Liu Yu, a Song official who had joined the Jin in 1128, gained the favor of the Jin emperor Taizong. Da Qi was formed in late 1130, and the Jin made Liu its emperor. Daming in Hebei was the first capital of Qi, before it moved to Kaifeng, the former capital of the Northern Song. The Qi government started drafting people into the military, tried to reform the government, and made laws that collected high taxes. It also provided many of the troops that fought the Song for seven years after its creation.

The Jin gave Qi more freedom than the first puppet government of Chu. But Liu Yu still had to obey the Jurchen generals. With Jin support, Da Qi invaded the Song in November 1133. Li Cheng, a Song general who had switched sides to Qi, led the attack. Xiangyang and nearby areas fell to his army. The capture of Xiangyang on the Han River gave the Jurchens a way into the central Yangtze River valley. Their push south was stopped by General Yue Fei. In 1134, Yue Fei defeated Li and took back Xiangyang and its surrounding areas.

Later that year, however, Qi and Jin started a new attack further east along the Huai River. For the first time, Gaozong officially spoke out against Da Qi. The armies of Qi and Jin won some battles in the Huai valley, but they were pushed back by Han Shizhong near Yangzhou and by Yue Fei at Luzhou (modern Hefei). Their sudden retreat in 1135, because Jin Emperor Taizong had died, gave the Song time to regroup.

The war started again in late 1136 when Da Qi attacked the Huainan areas of the Song. Qi lost a battle at Outang (in modern Anhui) against a Song army led by Yang Qizhong. This victory boosted Song morale, and the military commissioner Zhang Jun convinced Gaozong to plan a counterattack. Gaozong first agreed, but he stopped the counterattack when an officer named Li Qiong killed his superior and joined the Jin with 30,000 soldiers. This rebellion happened because Zhang Jun tried to take back government control over the regional military commanders, as the court had allowed them more freedom during the chaos of the Jin invasion.

Meanwhile, Emperor Xizong took over the Jin throne from Taizong. He pushed for peace. He and his generals were disappointed with Liu Yu's military failures and believed Liu was secretly working with Yue Fei. In late 1137, the Jin reduced Liu Yu's title and ended the state of Qi. The Jin and Song started peace talks again.

Song Counterattack and Peace Talks

Gaozong promoted Qin Hui in 1138 and put him in charge of talks with the Jin. Yue Fei, Han Shizhong, and many other officials at court criticized the peace efforts. Qin, using his control of the Censorate (a government office that watched over officials), removed his enemies and continued negotiations.

In 1138, the Jin and Song agreed to a treaty that set the Yellow River as the border between the two states and recognized Gaozong as a "subject" of the Jin. But because there was still opposition to the treaty in both the Jin and Song courts, it never fully took effect.

A Jurchen army led by Wuzhu invaded in early 1140. The Song counterattack that followed gained a lot of land. Song general Liu Qi won a battle against Wuzhu at Shunchang (modern Fuyang in Anhui). Yue Fei was put in charge of the Song forces defending the Huainan region. However, instead of going to Huainan, Wuzhu retreated to Kaifeng, and Yue's army followed him into Jin territory. This was against an order from Gaozong that told Yue not to attack. Yue captured Zhengzhou and sent soldiers across the Yellow River to start a peasant rebellion against the Jin.

On July 8, 1140, at the Battle of Yancheng, Wuzhu launched a surprise attack on Song forces with a huge army. Yue Fei directed his cavalry to attack the Jurchen soldiers and won a major victory. He continued into Henan, where he recaptured Zhengzhou and Luoyang. Later in 1140, Yue was forced to retreat after the emperor ordered him to return to the Song court.

Emperor Gaozong wanted to make a peace treaty with the Jurchens and wanted to control the military more. The military attacks by Yue Fei and other generals were getting in the way of peace talks. The government weakened the military by giving Yue Fei, Han Shizhong, and Zhang Jun (1086–1154) titles that took away their direct command over the Song armies. Han Shizhong, who was against the treaty, retired. Yue Fei also announced his resignation as a protest. In 1141, Qin Hui had him imprisoned for disobeying orders. Accused of disloyalty, Yue Fei died in jail on Qin's orders in early 1142. Jurchen pressure during the peace talks might have played a role, but Qin Hui's alleged secret cooperation with the Jin has never been proven.

After his death, Yue Fei became a national hero for defending the Southern Song. Qin Hui was later seen as a traitor by historians. The real Yue Fei was different from the later stories about him. Contrary to popular legends, Yue was just one of many generals who fought against the Jin in northern China. Traditional stories have also blamed Gaozong for Yue Fei's death and for giving in to the Jin. Qin Hui, in a reply to Gaozong's thanks for the successful peace talks, told the emperor that "the decision to make peace was entirely Your Majesty's. Your servant only carried it out; what achievement was there in this for me?"

The Treaty of Shaoxing

On October 11, 1142, after about a year of talks, the Treaty of Shaoxing was officially agreed upon, ending the conflict between the Jin and the Song. According to the treaty, the Huai River, north of the Yangtze, was set as the border between the two states. The Song agreed to pay a yearly amount of 250,000 taels of silver and 250,000 packs of silk to the Jin.

The treaty made the Southern Song dynasty a vassal of the Jin. The document called the Song the "insignificant state" and the Jin the "superior state." The original text of the treaty has not survived in Chinese records, which shows how humiliating it was considered. The details of the agreement were found in a Jurchen biography. Once the treaty was settled, the Jurchens retreated north, and trade between the two empires started again. The peace from the Treaty of Shaoxing lasted for the next 70 years, but it was broken twice by new wars.

Later Wars and the Fall of Jin

Wanyan Liang's War

Wanyan Liang became the fourth emperor of the Jin dynasty in 1150 after taking power from Emperor Xizong. Wanyan Liang saw himself as a Chinese emperor and planned to unite China by conquering the Song. In 1158, he claimed the Song had broken the 1142 peace treaty by getting horses, which he used as a reason for war. He started an unpopular draft that caused widespread unrest. Anti-Jin revolts broke out among the Khitans and in Jin provinces near the Song border. Wanyan Liang did not allow disagreement, and anyone who opposed the war was severely punished.

The Song had been warned about Wanyan Liang's plan. They prepared their defenses along the border, especially near the Yangtze River. But Emperor Gaozong's indecisiveness made things difficult. Gaozong wanted peace and didn't want to provoke the Jin. Wanyan Liang began the invasion in 1161 without officially declaring war. Jurchen armies, led by Wanyan Liang himself, left Kaifeng on October 15, reached the Huai River border on October 28, and marched towards the Yangtze. The Song lost the Huai region to the Jurchens but captured a few Jin areas in the west, slowing the Jurchen advance. A group of Jurchen generals were sent to cross the Yangtze near Caishi (south of Ma'anshan) while Wanyan Liang set up a base near Yangzhou.

The Song official Yu Yunwen was in charge of the army defending the river. The Jurchen army was defeated while attacking Caishi between November 26 and 27 during the Battle of Caishi. The Song navy's paddle-wheel ships, armed with trebuchets that fired gunpowder bombs, easily defeated the Jin fleet's lighter, hastily built ships. The bombs launched by the Song contained mixtures of gunpowder, lime, iron scraps, and a poison, likely arsenic.

Traditional Chinese accounts see this as the turning point of the war, a military upset that saved southern China from the northern invaders. They say it was as important as the Battle of Fei River in the 4th century. Song accounts from that time claimed that 18,000 Song soldiers defeated a Jurchen army of 400,000 soldiers. Modern historians are more doubtful and think the Jurchen numbers are exaggerated. Song historians might have confused the number of Jurchen soldiers at Caishi with the total number of soldiers under Wanyan Liang. The battle was not as one-sided as traditional accounts suggest, and the Song had many advantages over the Jin. The Song fleet was larger, and the Jin couldn't use their best weapon, cavalry, in a naval battle.

A modern study of the battlefield shows it was a smaller battle, though the victory did boost Song morale. The Jin lost, but only had about 4,000 casualties, and the battle wasn't fatal to their war effort. It was Wanyan Liang's bad relationships with his generals, who disliked him, that ruined the Jin's chances of victory. On December 15, Wanyan Liang was killed in his military camp by unhappy officers. He was replaced by Emperor Shizong, who had long resented Wanyan Liang. Shizong was pressured to end the unpopular war with the Song and ordered the Jin forces to withdraw in 1162. Emperor Gaozong retired from the throne that same year. His poor handling of the war with Wanyan Liang was one reason for his abdication. Small fights between the Song and Jin continued along the border but stopped in 1165 after a new peace treaty was negotiated. There were no major changes in territory. The treaty said that the Song still had to pay the yearly amount, but it was renamed from "tribute" (which meant a lower status) to "payment."

Song Seeks Revenge

The Jin were weakened by pressure from the rising Mongols to the north, a series of floods (including a major Yellow River flood in 1194), and droughts and locusts in the south. The Song learned about the Jin's problems from their ambassadors, who visited the Jin capital twice a year. The Song started to provoke their northern neighbor.

The fighting was started by chancellor Han Tuozhou. The Song Emperor Ningzong (r. 1194–1224) wasn't very interested in the war. Under Han Tuozhou's guidance, preparations for the war were slow and careful. The court honored the hero Yue Fei, and Han arranged for historical records to be published that justified war with the Jin. From 1204 onwards, Chinese armed groups raided Jurchen settlements. Han Tuozhou was made head of national security in 1205. The Song funded rebels in the north who claimed to be loyal to the Song. These early clashes grew, partly encouraged by Song officials who wanted revenge, and war against the Jin was officially declared on June 14, 1206. The document announcing the war claimed the Jin had lost the Mandate of Heaven (meaning they were unfit to rule) and called for a rebellion of Han Chinese against the Jin state.

Song armies led by general Bi Zaiyu captured the lightly defended border city of Sizhou but suffered heavy losses against the Jurchens in Hebei. The Jin pushed back the Song and moved south to surround the Song town of Chuzhou. Bi defended the town, and the Jurchens withdrew after three months. By the fall of 1206, however, the Jurchens had captured multiple towns and military bases. The Jin started an attack against Song areas in the central part of the war, capturing Zaoyang and Guanghua. By the fall of 1206, the Song attack had failed badly. Soldier morale dropped as weather worsened, supplies ran out, and hunger spread, forcing many to desert. The massive defections of Han Chinese in northern China that the Song had expected never happened.

However, a notable betrayal did occur on the Song side: Wu Xi, the governor-general of Sichuan, switched sides to the Jin in December 1206. The Song had relied on Wu's success in the west to draw Jin soldiers away from the eastern front. He had attacked Jin positions earlier in 1206, but his army of about 50,000 men had been pushed back. Wu's defection could have meant the loss of the entire western front of the war. But Song loyalists killed Wu on March 29, 1207, before Jin troops could take control of the surrendered areas. An Bing was given Wu Xi's position, but the Song forces in the west fell apart after Wu's death, and commanders fought among themselves.

Fighting continued in 1207, but by the end of that year, the war was stuck. The Song was now on the defensive, while the Jin failed to gain ground in Song territory. The war cost both sides much more than they gained. Han Tuozhou's aggressive policies against the Jurchens had made him unpopular. Empress Yang and Shi Miyuan, his most powerful political rivals, used this to gain support among other court officials, which led to his downfall. On November 24, 1207, Han Tuozhou was stopped on his way to court, dragged outside the Imperial palace, and killed by the Imperial Palace Guards. His accomplice Su Shidan was executed, and other officials connected to Han were dismissed or exiled. Since neither side wanted to continue the war, they returned to negotiations. A peace treaty was signed on November 2, 1208, and the Song payments to the Jin were restarted. The Song's yearly payment increased by 50,000 taels of silver and 50,000 packs of fabric. The treaty also said that the Song had to give the Jin the head of Han Tuozhou, who the Jin blamed for starting the war.

Jin–Song War During the Rise of the Mongols

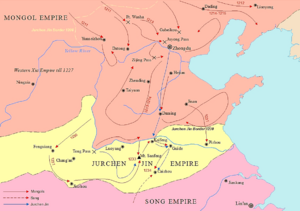

The Mongols, a group of nomadic tribes, had united in the mid-12th century. They and other steppe nomads sometimes raided the Jin empire from the northwest. The Jin avoided punishing them and tried to keep them happy, similar to how the Song had dealt with them. The Mongols, who used to pay tribute to the Jin, ended their vassalage in 1210 and attacked the Jin in 1211.

Because of this, the Song court discussed ending their payments to the weakened Jin. But they again chose not to anger the Jin. They refused Western Xia's offers to ally against the Jin in 1214. Meanwhile, in 1214, the Jin retreated from their besieged capital of Zhongdu to Kaifeng, which became the new capital. As the Mongols expanded, the Jin lost territory and attacked the Song in 1217 to make up for their shrinking land. Occasional Song raids against the Jin were the official reason for the war. Another likely reason was that conquering the Song would give the Jin a place to escape if the Mongols took control of the north.

Shi Miyuan, the chancellor of Song Emperor Lizong, was hesitant to fight the Jin and delayed the declaration of war for two months. Song generals largely acted on their own, allowing Shi to avoid blame for their military mistakes. The Jin advanced across the border from the center and western fronts. Jurchen military successes were limited, and the Jin faced repeated raids from the neighboring state of Western Xia. In 1217, the Song generals Meng Zongzheng and Hu Zaixing defeated the Jin and stopped them from capturing Zaoyang and Suizhou.

A second Jin campaign in late 1217 did slightly better than the first. In the east, the Jin made little progress in the Huai River valley. But in the west, they captured Xihezhou and Dasan Pass (modern Shaanxi) in late 1217. The Jin tried to capture Suizhou again in 1218 and 1219 but failed. A Song counterattack in early 1218 captured Sizhou. In 1219, the Jin cities of Dengzhou and Tangzhou were looted twice by a Song army led by Zhao Fang. In the west, command of the Song forces in Sichuan was given to An Bing, who had been dismissed from this position earlier. He successfully defended the western front but couldn't advance further because of local uprisings. The Jin tried to demand money from the Song but never received it. In the last of the three campaigns, in early 1221, the Jin captured the city of Qizhou deep in Song territory. Song armies led by Hu Zaixing and Li Quan defeated the Jin, who then withdrew. In 1224, both sides agreed on a peace treaty that ended the yearly payments to the Jin. Diplomatic visits between the Jin and Song also stopped.

The Mongol–Song Alliance

In February 1233, the Mongols took Kaifeng after a siege of more than 10 months. The Jin court retreated to the town of Caizhou. In 1233, Emperor Aizong of the Jin sent diplomats to ask the Song for supplies. Jin messengers told the Song that the Mongols would invade the Song after they finished with the Jin—a prediction that later came true. But the Song ignored the warning and refused the request. Instead, they formed an alliance with the Mongols against the Jin. The Song provided supplies to the Mongols in return for parts of Henan.

The Jin dynasty collapsed when Mongol and Song troops defeated the Jurchens at the siege of Caizhou in 1234. General Meng Gong led the Song army against Caizhou. The Jin's second-to-last emperor, Emperor Aizong, took his own life. His short-lived successor, Emperor Mo, was killed in the town a few days later. The Mongols later turned their attention towards the Song. After decades of war, the Song dynasty also fell in 1279, when the remaining Song loyalists lost to the Mongols in a naval battle near Guangdong.

What Changed Because of the Wars

Cultural and Population Shifts

Jurchen people from the northeastern parts of Jin territory moved and settled in the Jin-controlled lands of northern China. They made up less than ten percent of the total population. The two to three million ruling Jurchens were a minority in a region that was still mostly inhabited by 30 million Han Chinese. The Jurchens' move south caused the Jin to change their government from a loose collection of tribes to a more organized, Chinese-style dynasty.

The Jin government at first promoted a unique Jurchen culture while also adopting the Chinese imperial government system. But over time, the empire gradually became more like Chinese culture. The Jurchens learned to speak Chinese fluently, and the ideas of Confucianism were used to make their government seem legitimate. Confucian state rituals were adopted during the reign of Emperor Xizong (1135–1150). The Jin started using imperial exams based on the Confucian Classics, first in regions and then for the whole empire. The Classics and other Chinese literature were translated into Jurchen and studied by Jin scholars. The Khitan small script, which came from Chinese writing, became the basis for a national writing system for the empire, the Jurchen script. All three scripts were used by the government. Jurchen families started using Chinese personal names along with their Jurchen names.

Wanyan Liang (r. 1150–1161) strongly supported the Jurchens becoming more Chinese. He made policies to encourage it. Wanyan Liang had learned about Song culture since he was a child, and his copying of Song practices earned him the Jurchen nickname of "aping the Chinese." He studied Chinese classics, drank tea, and played Chinese chess for fun. Under his rule, the main government center of the Jin state was moved south from Huining. He made Beijing the main Jin capital in 1153. Palaces were built in Beijing and Kaifeng, while the older homes of Jurchen chieftains further north were torn down.

The emperor's political changes were linked to his desire to conquer all of China and to present himself as a Chinese emperor. The chance of conquering southern China was cut short by Wanyan Liang's assassination. Wanyan Liang's successor, Emperor Shizong, was less keen on becoming more Chinese and reversed several of Wanyan Liang's orders. He approved new policies to slow down the Jurchens' assimilation. Shizong's bans were dropped by Emperor Zhangzong (r. 1189–1208), who promoted changes that made the dynasty's political structure more like that of the Song and Tang dynasties. Despite cultural and population changes, military conflicts between the Jin and the Song continued until the fall of the Jin.

In the south, the Song dynasty's retreat led to big population changes. The number of refugees from the north who moved to Lin'an and Jiankang (modern Hangzhou and Nanjing) eventually became larger than the number of original residents, whose numbers had decreased from repeated Jurchen raids. The government encouraged peasant migrants from the southern provinces of the Song to move to the less populated areas between the Yangtze and the Huai rivers.

The new capital, Lin'an, grew into a major center for business and culture. It went from being a regular city to one of the world's largest and most successful. During his visit to Lin'an in the Yuan dynasty (1260–1368), when the city was not as wealthy as it had been under the Song, Marco Polo said that "this city is greater than any in the world." Once taking back northern China seemed less likely and Lin'an grew into an important trading city, the government buildings were expanded and renovated to better suit its status as an imperial capital. The modest imperial palace was expanded in 1133 with new covered walkways and in 1148 with an extension of the palace walls.

The loss of northern China, which was the cultural heart of Chinese civilization, reduced the Song dynasty's regional standing. After the Jurchen conquest of the north, Korea recognized the Jin, not the Song, as the true dynasty of China. The Song's military failures made it seem like a subordinate to the Jin, turning it into a "China among equals." However, the Song economy recovered quickly after the move south. Government income from taxing foreign trade almost doubled between the end of the Northern Song era in 1127 and the final years of Gaozong's reign in the early 1160s. The recovery wasn't even everywhere; areas like Huainan and Hubei that were directly affected by the war took decades to return to their pre-war levels. Despite many wars, the Jin remained one of the Song's main trading partners. Song demand for foreign products like fur and horses continued. Historian Shiba Yoshinobu believes that Song trade with the north was profitable enough to make up for the silver paid yearly to the Jin.

The Jin–Song Wars were one of several wars in northern China that caused a large migration of Han Chinese from northern China to southern China. In 1126–1127, over half a million people fled from northern China to southern China, including the famous poet Li Qingzhao. One part of the Confucius family, led by Duke Yansheng Kong Duanyou, moved south with Southern Song emperor Gaozong. His brother Kong Duancao stayed in Qufu and became the Duke Yansheng for the Jin dynasty. A part of the Zengzi family also moved south with the Southern Song, while the other part stayed in the north.

However, there was also a reverse migration after the war, with Han Chinese moving from the Southern Song towards Jin-ruled northern China. This caused southern China's population to shrink and northern China's population to grow.

New Weapons: Gunpowder in Warfare

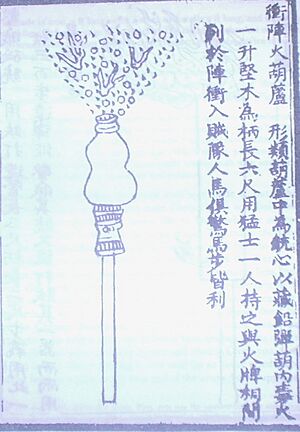

The battles between the Song and the Jin led to the invention and use of gunpowder weapons. There are reports that the fire lance, one of the earliest ancestors of the firearm, was used by the Song against the Jurchens besieging De'an (modern Anlu in eastern Hubei) in 1132. This happened during the Jin invasion of Hubei and Shaanxi. The weapon was a spear with a flamethrower attached, capable of firing projectiles from a barrel made of bamboo or paper. They were built by soldiers under Chen Gui, who led the Song army defending De'an. The fire lances used by Song soldiers at De'an were made to destroy the Jin's wooden siege engines, not for fighting infantry. Song soldiers made up for the weapon's limited range and movement by timing their attacks on the Jin siege engines, waiting until they were close enough. Later fire lances used metal barrels, fired projectiles farther and with more force, and could be used against foot soldiers.

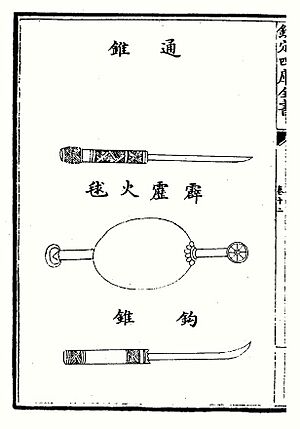

Early simple bombs like the huopao fire bomb and the huopao bombs launched by trebuchets were also used as incendiary (fire-starting) weapons. The defending Song army used huopao during the first Jin siege of Kaifeng in 1126. On the other side, the Jin launched fire bombs from siege towers down onto the city. In 1127, huopao were used by the Song troops defending De'an and by the Jin soldiers attacking the city. The government official Lin Zhiping suggested making incendiary bombs and arrows required for all warships in the Song navy. At the battle of Caishi in 1161, Song ships fired pili huoqiu (also called pili huopao bombs) from trebuchets against the ships of the Jin fleet. The bomb's gunpowder mixture contained powdered lime, which produced blinding smoke when the bomb's casing broke. The Song also used incendiary weapons at the battle of Tangdao in the same year.

Gunpowder was also used in arrows in 1206 by a Song army in Xiangyang. These arrows were most likely incendiary weapons, but they might have also worked like early rockets. At the Jin siege of Qizhou in 1221, the Jurchens fought the Song with gunpowder bombs and arrows. The Jin's tiehuopao ("iron huopao'"), which had cast iron casings, are the first known hard-casing bombs. The bomb needed to be able to explode to break through the iron casing. The Song army had a large supply of incendiary bombs, but there are no reports of them having a weapon similar to the Jin's exploding bombs. Someone who was at the siege wrote that the Song army at Qizhou had 3000 huopao, 7000 incendiary gunpowder arrows for crossbows and 10000 for bows, as well as 20000 pidapao, which were probably leather bags filled with gunpowder.

See also

- History of the Song dynasty

- Timeline of the Jin–Song wars

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |