John Crichton-Stuart, 2nd Marquess of Bute facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

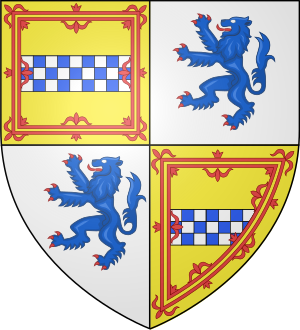

The Marquess of Bute

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 10 August 1793 |

| Died | 18 March 1848 (aged 54) |

| Resting place | Kirtling |

| Title | 2nd Marquess of Bute |

| Known for | Construction of Cardiff Docks |

| Residence | Mount Stuart House |

| Spouse(s) | Lady Maria North Lady Sophia Rawdon-Hastings |

| Issue | John Patrick Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute |

| Parents | John Stuart, Lord Mount Stuart and Lady Elizabeth McDouall-Crichton |

|

|

|

John Crichton-Stuart, 2nd Marquess of Bute (born August 10, 1793 – died March 18, 1848) was a very rich and important person in Britain. He lived during the Georgian era and early Victorian era. He was known for developing the coal and iron industries in South Wales. He also built the famous Cardiff Docks.

John's father died soon after he was born. He was raised by his mother and then his grandfather. He traveled a lot in Europe and went to Cambridge University. He got an eye problem and could only see a little for the rest of his life.

He inherited huge amounts of land and money. In 1818, he married Lady Maria North. They lived a quiet life at Mount Stuart House in Scotland. John was a serious but very hardworking person. He was great at managing his lands. He spent his days writing to his managers and visiting his properties twice a year. Maria and John did not have children. Maria died in 1841. Four years later, John married Lady Sophia Rawdon-Hastings. Their son, John, was born in 1847.

John was a member of the House of Lords, which is part of the British Parliament. He was a political conservative, meaning he liked traditional ways. He usually only got involved in national debates if they affected his businesses. John quickly saw the huge wealth in the coal fields of South Wales. He started to make money from them using local iron makers and coal miners.

He built the Cardiff Docks, a massive project. Even though it cost much more than planned, it helped export more iron and coal. This made his lands in Glamorganshire even more valuable. When the Merthyr Rising happened in 1831, John led the government's response from Cardiff Castle. He sent soldiers and spies and kept the government in London informed. People at the time called him "the creator of modern Cardiff." When he died, he left a huge fortune to his son.

Contents

John's Early Life and Family

John was the son of John, Lord Mount Stuart, and Lady Elizabeth McDouall-Crichton. Both his parents came from rich, noble families. His father was set to become the Marquess of Bute. This meant he would own a lot of land in Scotland and South Wales. His mother was the only heir to the Crichton estates. These included over 63,980 acres of land in Scotland. John's father died in a riding accident in 1794. His younger brother, Patrick, was born later that year.

John first grew up at Dumfries House with his mother and grandmother. After they died, his grandfather, the 1st Marquess of Bute, took care of him. He traveled with his grandfather across England and Europe. His family thought he was very smart. In 1809, he went to Christ's College at Cambridge University. Over the next few years, he visited many places like the Mediterranean, Scandinavia, and Russia. He was very interested in how land could make money. During this time, he developed an eye problem. He became partially blind. This made it hard for him to travel without help or to be in bright lights. It was also difficult for him to read or write.

When his grandfathers died, John inherited all their lands and titles. He added Crichton to his last name. He held many important titles, like Marquess of Bute. He also had many official jobs, such as Lord Lieutenant of Glamorgan.

John had four main homes. These were Mount Stuart House in Scotland, Dumfries House, Luton Hoo in England, and Cardiff Castle in South Wales. He also had a house in London. John liked living at Mount Stuart House the most. He did not like London and only spent a few weeks a year at Cardiff Castle. Twice a year, he would travel from Scotland, through England, to Cardiff and his lands in South Wales.

Because of his poor eyesight and dislike for London's social life, John spent six years living quietly on the Isle of Bute. In 1818, he married his first wife, Lady Maria North. Maria was from a rich family and inherited a lot of money. People at the time thought Maria was kind, but she was often sick. They did not have any children. In 1820, a famous artist painted his portrait. In 1827, Maria inherited even more money from her father.

Historians describe John as serious and sometimes bossy. But he also had a strong sense of duty and worked very hard. He lived a quiet life compared to other rich people of his time. Because of his personality and bad eyesight, he did not enjoy hunting, shooting, or big parties. He also did not like horse racing or gambling. His wife's illnesses made him even more separate from other wealthy families. John was quite generous. He gave away about 7-8% of his income from South Wales to charity. He liked to fund local schools and build new churches. This also helped him keep people from joining other religious groups.

In 1841, Lady Maria died. John felt that his focus on building the docks had made her illness worse. He continued to receive income from her property after her death. In 1843, a fire destroyed the inside of Luton Hoo House. Most of its famous paintings were saved. John later sold the house.

In 1843, Queen Victoria made John a Knight of the Thistle. In 1845, John fell from his horse. This made his eye problems even worse. He remarried that same year to Lady Sophia Rawdon-Hastings. Sophia was a difficult person and did not get along with John's family. She became pregnant and gave birth to a child who did not survive. Their second child, also named John, was born in 1847.

John's relationship with his brother Patrick was often difficult. Patrick had different political views; he was more liberal. Although John helped Patrick become a Member of Parliament in 1818, he removed him in 1831 because of their disagreements.

John as a Landowner and Business Leader

Managing His Estates

John wanted to make his different estates as profitable as possible. He was a very active and ambitious manager. He always had new ideas for his properties. He spent most of his time managing them. Even with his poor eyesight, he wrote at least six letters to his managers every day. He knew a lot about his various lands and businesses. For example, he kept up with news in Glamorgan by reading local Welsh newspapers from his home in Scotland. He also wrote letters to important local people. John knew his land holdings were too spread out to manage easily. He tried to sell his Luton estates in the early 1820s but couldn't get a good price. He finally sold them in the early 1840s. By 1845, Luton and Luton Hoo included about 3,600 acres.

John owned almost all his lands completely, which was unusual for a rich person at that time. This meant he had full control over them. He managed his network of estates and managers himself. Edward Richards became the main manager for the Glamorgan estates by 1824. He handled both land and political matters. But John still made the final decisions on even small things. This included choosing buttons for school uniforms. This could cause long delays as letters went between South Wales and Scotland. As the Glamorgan estates grew more complex, more managers were hired. But they all reported separately to John, which put a lot of pressure on him.

On the Isle of Bute, John bought more land and expanded his properties.

Developing Glamorganshire

John was very involved in the changes happening in Glamorganshire in the early 1800s. The region saw huge economic and social changes very quickly. The population almost tripled in 40 years. Industrial production soared. For example, iron output increased from 34,000 to 277,000 tons between 1796 and 1830. Industry and mining became the main types of work. John helped lead these changes. He turned his South Wales estate into a major industrial business.

John's lands in Glamorgan were spread out. He bought more land around Cardiff between 1814 and 1826. This helped him connect his properties. But rising land prices and the cost of the docks stopped this expansion. John borrowed a lot of money. He inherited debts of £62,500, but by the time he died, he owed £493,887. It was hard to manage this debt, especially in the early 1840s. But John believed his investments would pay off greatly in the future.

The growing economy in South Wales meant more housing was needed for workers. John did not want to sell his land for housing. He also didn't see much profit in building and renting houses himself. But he did lease land in growing towns and mining areas for development. He usually offered 99-year leases. These contracts did not allow people to buy the land or automatically renew their lease. This later caused big problems for his son and grandson. John let the people leasing the land design the early buildings. But he was not happy with the results. So, he started to approve designs himself. He planned some grand streets in Cardiff and saved open areas for parks. However, very little money was spent on sewage and drainage systems. A report in 1850 showed this led to cholera outbreaks in the town.

In the early 1800s, scientists found that the Glamorgan valleys had a lot of coal. John already owned coal mines in another area. He had more surveys done in 1817 and 1823–24. These showed that huge profits could be made from the coal. This included coal under his own lands and under common lands he could claim. John worked to get control of these coal fields. He managed a few coal mines directly. But because of the high costs, he usually preferred to lease out his coal fields. He would then get a payment for the coal mined. The profits from coal increased a lot, from £872 in 1826 to £10,756 in 1848–49.

Building the Cardiff Docks

Between 1822 and 1848, John was key in creating the Cardiff Docks. One of his staff first suggested the idea in 1822. They thought Cardiff could become a major port for exporting coal and iron. The old port was small and not very good. The new port would make money for John from shipping fees. It would also increase the value of his lands in Cardiff and his coal royalties. At first, John was against plans for docks by local iron makers. But then he changed his mind and pushed for his own plan.

The first step was to build a new dock and a connecting canal in Cardiff. This would make the old canal useless. It was estimated to cost £66,600. Some people thought this was a "wild idea." Parliament approved the plan in 1830, even with opposition from local canal companies. The project was much harder than planned. John became very annoyed with almost everyone involved. But the dock opened successfully in 1839. The costs were much higher than expected. Instead of £66,600, it cost £350,000. John had to use his local lands as collateral to borrow money to finish the project. To make things worse, the docks did not get as much ship traffic as he hoped at first. John thought this was because iron makers and others were trying to ruin him.

John then put pressure on shipping companies to use his docks instead of the old canal. He also used his old feudal rights to force shippers to move their docks to his new ones. His efforts worked. Trade through the docks started at 8,000 tons in 1839. It quickly rose to 827,000 tons by 1849. Between 1841 and 1848, the docks made almost £68,000. This was not as much as expected compared to the huge investment. Future Marquesses would have to keep investing and expanding the docks for many decades.

John's Role in Politics

National Politics

John lived during a time when the British government was changing. The British Parliament had two parts: the House of Lords (for nobles) and the House of Commons (for elected officials). Voting rules were very different across the country. In many places, only a few local people could vote. Some members of the House of Lords, called "patrons," could control these "closed" seats. This meant they could choose who became a Member of Parliament. People started to criticize this system.

John was a member of the House of Lords. He could vote on national issues. But he usually only attended when there were votes about his lands or businesses. When he did vote, he was a moderate conservative. He followed the ideas of the Duke of Wellington, a leading conservative politician. John supported allowing Catholics more rights and was against slavery. He was also in favor of ending the Corn Laws, which kept food prices high. However, he strongly opposed changing the voting system or separating the Church of England or Scotland from the government. John believed poor people should work. He was not a good public speaker.

John also tried to control the votes of members in the House of Commons. He did this mainly to pass laws that helped his businesses. For example, he influenced voting in Cardiff. He had to choose his candidates carefully. He also used his control over leases and rents to make sure his candidates were elected.

In 1832, the Reform Act was passed. This law allowed more people to vote across the country. The number of voters on the Isle of Bute increased, and John still controlled who became the Member of Parliament there. After these changes, John secretly supported a conservative newspaper. He paid for its losses for many years to gain more support in the county.

From 1842 to 1846, John was Her Majesty's High Commissioner to the Church of Scotland. He was known for being a generous host in this role. He was in office during a big split in the Church of Scotland, called "the Disruption." Many ministers left the official Church to form the Free Church. John took a strong stand against this. For example, he fired his head gardener for joining the Free Church.

Local Control in South Wales

Re-establishing Authority

John wanted to control the local government around Cardiff. He saw this as his right and duty as a major landowner. But when he inherited his lands, the Bute family's power in Glamorganshire had become weak. There were also tensions between John and the new factory owners in the region, like John Guest. John saw himself as a kind feudal lord in South Wales. He thought the local iron makers were arrogant and too powerful.

However, John could appoint the Constable of Cardiff Castle. This person acted as the mayor of Cardiff. They ran the town council and had a lot of power to appoint local officials. In 1815, John became the Lord-Lieutenant of the county. This gave him the right to suggest new judges and other civic jobs. People who wanted these jobs were told to vote for John's representatives in elections. He also used his power over the local militia to make them vote for his candidates. If people voted against John, they could lose charitable donations and support. His control of the Cardiff Docks later also helped him gain influence.

In 1817, a local lawyer named John Wood died in a financial scandal. John decided to appoint two of Wood's rivals to important positions. This was meant to show John's power and break the Wood family's control. But it caused a big political fight. The Wood family fought back, saying John should not control Welsh affairs from Scotland. John tried to hurt the Wood family's bank. He also filled the town council with his own people in 1818. The Woods took legal action, challenging John's power. There was violence against John that summer. But John's supporters in Cardiff won the elections that year. This confirmed John's power over the town council.

The Merthyr Rising

John played a role in the Merthyr Rising. This was a large, armed protest by workers in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales, in 1831. Workers in Glamorgan had become very angry in the 1820s. Wages were good in some years, but they dropped quickly during bad times. This left many people very poor. Living conditions in the fast-growing industrial towns were terrible. Child deaths were very high. In 1831, there was a severe economic downturn. Wages fell, and food prices rose. People also complained a lot about debt courts.

By late 1830, it looked like trouble was coming to South Wales. John traveled from Scotland to Cardiff Castle in May 1831. Tensions grew between different political groups. Radical protests happened in Merthyr Tydfil in May. Crowds burned effigies of conservative politicians. Violence broke out, and people were arrested on May 10. The angry crowd freed the prisoners. Local authorities lost control of the town. A general uprising began on May 30.

Two local officials were stuck in an inn in Merthyr Tydfil. They wrote an urgent letter to John in Cardiff Castle. They asked for advice on calling in the army. They also asked if John had prepared the local militia. Huge crowds marched on local iron works, stopping production. John received the messages that afternoon. He started to gather the local armed forces. He waited until morning, hoping for better news. But messengers brought more desperate news. So, the armed forces were sent. Meanwhile, 80 soldiers had arrived in the inn from another town. John kept the government in London informed by letter.

On May 3, the soldiers reached the inn. The radical crowds outside had grown to between 7,000 and 10,000 people. Tensions rose. The Riot Act was read in English and Welsh. Violence erupted. The crowds tried to take the soldiers' weapons. The soldiers fired their guns. The town's workers became very angry. They started searching the region for weapons. A messenger escaped the inn to reach John in Cardiff. John quickly called up all the remaining armed forces he had. He also sent a military leader into Merthyr to replace the injured commander of the soldiers.

The men in the inn moved to another house. They were joined by more armed forces, bringing their numbers to about 300. But not all of them were armed. They faced increasingly well-armed rebels. John became worried about how strong the rebels were. John sent spies into the rebel groups. A nearby castle was used as a lookout post. John also mobilized retired soldiers. He used them to bring more weapons from Cardiff to his men. He was careful, though, in case the weapons fell into the rebels' hands. John's forces stopped the rebels from entering the houses. John also arrested possible rebels in Cardiff.

On May 16, John's forces were able to move into Merthyr. They pushed forward, taking advantage of the rebels' poor communication. The uprising collapsed. Over the next few days, the authorities regained control. They made arrests and forced workers back to their jobs. Government investigations into the event began. John provided reports to the government in London. Afterward, one of the rebels, Richard Lewis, was hanged in Cardiff. This execution was controversial. It is not known if John, who had left for London by then, approved of the decision.

Later Years

Concerns about possible violent outbreaks continued for many years. A movement called Chartism became popular in the region in the late 1830s. This worried John a lot in 1839. He encouraged the army to be ready to deal with this threat. John started to suggest creating a police force to stop problems in the northern valleys. For once, he worked with the local iron makers to get this plan approved. In 1841, the plan was passed. A chief police officer and headquarters were set up that year.

In 1835, a new law changed local government. It created a new town council structure with an elected mayor. John had to work harder to keep his influence over the new council. But he was successful. In practice, the elected officials were controlled by John and his interests.

John's Death and Legacy

John died in Cardiff on March 18, 1848. He was buried in Kirtling, next to his first wife, Maria. His funeral had 31 carriages and drew large crowds. However, the local iron makers did not attend. National newspapers did not cover his death much. But the local Daily Chronicle praised John's unusual achievement in building up the industries of his South Wales estates. It especially praised his role in building the Cardiff Docks. The Cardiff Docks, which opened in 1837, led the press to call John "the creator of modern Cardiff." The docks continued to change the city for the rest of the century. They also became a financial responsibility for John's successors. The constant need for investment partly balanced the huge profits his son made from the South Wales coal fields.

People across Glamorgan raised money to pay for a statue of him. It was put up in Cardiff's High Street in 1853. In 2000, the statue, which is Cardiff's oldest, was moved to Bute Square. But the location was renamed Callaghan Square in 2002. This led to ideas that John's statue might be moved again, possibly outside Cardiff Castle.