John Theophilus Desaguliers facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Theophilus Desaguliers

|

|

|---|---|

John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683–1744)

|

|

| Born |

Jean Théophile Desaguliers

12 March 1683 |

| Died | 29 February 1744 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | French, English |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Known for | Dissemination of Newtonian ideas, planetarium, ventilation, hydraulics, steam engines |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1734) Copley Medal (1736) Copley Medal (1741) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural philosophy and engineering |

| Institutions | University of Oxford |

| Academic advisors | John Keill |

| Notable students | Stephen Demainbray Willem 's Gravesande Stephen Gray |

| Influences | Isaac Newton |

John Theophilus Desaguliers (born March 12, 1683 – died February 29, 1744) was a British scientist, clergyman, and engineer. He was also a Freemason. In 1714, he became a member of The Royal Society, working as an assistant to the famous scientist Isaac Newton.

Desaguliers studied at Oxford. He became well-known for teaching Newton's scientific ideas and showing how they could be used in real life. He did this through public lectures. A very important supporter of his work was James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos. As a Freemason, Desaguliers helped the first Grand Lodge in London become very successful in the early 1720s. He even served as its third Grand Master.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

John Theophilus Desaguliers was born in La Rochelle, France. His father, Jean Desaguliers, was a Protestant minister. He had to leave France because Protestants were being forced out by the government. John and his mother later joined his father in Guernsey.

In 1692, his family moved to London. His father started a French school there. After his father died, John, who now used the English version of his name, went to school until 1705. He then went to Christ Church, Oxford. He studied the usual subjects and earned his first degree in 1709.

He also went to lectures by John Keill. Keill used exciting demonstrations to explain difficult ideas in natural philosophy. Natural philosophy was the study of nature and the universe, which we now call science. When Keill left Oxford, Desaguliers continued giving these lectures. He earned his master's degree in 1712. Later, in 1719, Oxford gave him an honorary doctorate. People often called him Dr. Desaguliers after that.

Lecturer and Science Promoter

In 1712, Desaguliers moved back to London. He started offering public lectures on "Experimental Philosophy." This meant he would show experiments to explain scientific ideas. He became very popular, giving over 140 courses of about 20 lectures each. He taught about mechanics, how liquids and gases work, optics (light), and astronomy (space).

He always updated his lectures and designed his own equipment. One famous piece was a planetarium. This machine showed how the planets move around the sun. In 1717, he even gave lectures in French to King George I and his family at Hampton Court Palace.

Working with the Royal Society

In 1714, Isaac Newton, who was the President of The Royal Society, asked Desaguliers to be the demonstrator for their weekly meetings. Soon after, Desaguliers became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He helped promote Newton's ideas. He also made sure the meetings stayed focused on science after Newton died in 1727.

Desaguliers wrote over 60 articles for the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, which is a science journal. He won the Society's important Copley Medal three times: in 1734, 1736, and 1741. His last award was for his work on electricity. He worked with Stephen Gray on this topic. Desaguliers even created the terms "conductor" and "insulator" for materials that either allow electricity to pass through or not.

Engineering and Inventions

Desaguliers used his scientific knowledge to solve real-world problems. He was interested in steam engines and how water moves (hydraulics). In 1721, he fixed a problem with the water supply in Edinburgh, Scotland.

He also became an expert in ventilation. He designed a more efficient fireplace. This fireplace was used in the House of Lords, where part of the British government meets. He also invented a "blowing wheel" that removed stale air from the House of Commons for many years.

Desaguliers studied how the human body works like a machine. He was friends with a strong man named Thomas Topham. Desaguliers wrote down many of the amazing feats Topham performed.

He also advised the group building the first Westminster Bridge in London. This bridge was finished after his death. Desaguliers also made important contributions to the study of friction, which is called tribology. He was one of the first to understand how things sticking together (adhesion) might play a role in friction.

Freemasonry Activities

Desaguliers was a member of a Lodge that met in London. This Lodge, along with three others, formed the first Grand Lodge of England on June 24, 1717. This new Grand Lodge grew quickly, and Desaguliers was very important to its early success.

He became the third Grand Master in 1719. He also helped James Anderson write the rules for Freemasons, which were published in 1723. He helped set up masonic charity, which helps people in need.

During a trip to the Netherlands in 1731, Desaguliers introduced Francis, Duke of Lorraine to Freemasonry. Francis later became the Holy Roman Emperor. Desaguliers also led the ceremony when Frederick, Prince of Wales, became a Freemason in 1731. He later became a chaplain (a religious leader) to the Prince.

Family Life

On October 14, 1712, John Theophilus Desaguliers married Joanna Pudsey. For most of their marriage, they lived in Westminster, London. This is where Desaguliers gave most of his lectures. Later, they had to move because of work on Westminster Bridge.

The Desaguliers had four sons and three daughters. Only two of their children lived past infancy. Their elder son, John Theophilus Jr. (1718–1751), became a clergyman. Their younger son, Thomas Desaguliers (1721–1780), had a successful military career in the Royal Artillery. He became a general and was known for applying science to cannons and gunnery. He also became a Fellow of the Royal Society. Thomas Desaguliers helped design the fireworks for the first performance of Handel's Music for the Royal Fireworks. He later worked for King George III.

Later Years and Legacy

John Theophilus Desaguliers suffered from gout for a long time. He died on February 29, 1744, in London. He was buried in the Savoy Chapel. This chapel was likely chosen because of its connection to French Protestants, honoring his family's background. Newspapers at the time called him "a gentleman universally known and esteemed."

Some people thought Desaguliers died poor, based on a poem by James Cawthorn. However, this was not true. He left his property to his elder son, who then published a second edition of his book, "Course of Experimental Philosophy." The poem was actually trying to show that scientists often didn't get enough money, not that Desaguliers himself was poor.

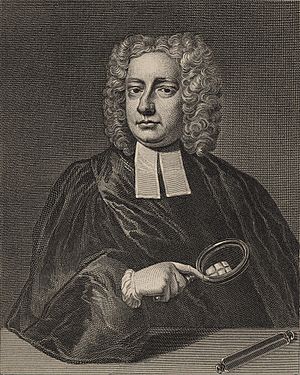

Portraits

There are a few known pictures of Desaguliers. Two engravings were made from a lost painting by Hans Hysing from around 1725. Another engraving was made from a lost painting by Thomas Frye from 1743, showing him as an older man. An engraving by Étienne-Jehandier Desrochers was likely made in 1735 when Desaguliers visited Paris. There is also an oil painting thought to be by Jonathan Richardson.

See also

In Spanish: John Theophilus Desaguliers para niños

In Spanish: John Theophilus Desaguliers para niños

- Electric charge

- Development of a practical steam engine

- Direct bonding

- Dynamometer

- Ventilation (architecture)

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |