John Wallace Crawford facts for kids

John Wallace ("Captain Jack") Crawford (1847–1917) was an American adventurer, writer, and teacher. He was known as "The Poet Scout." Captain Jack was a great storyteller about the Wild West. He became famous in American history as a popular performer in the late 1800s. He made a daring ride of 350 miles in six days. He carried news for the New York Herald newspaper to Fort Laramie. This news was about a big victory by General George Crook at the Battle of Slim Buttes. This happened during the Great Sioux War of 1876. This ride made him a national hero.

Contents

- Early Life & Adventures

- Black Hills Gold Rush

- War Correspondent

- The Great Sioux War

- General Crook's Horsemeat March

- Battle of Slim Buttes

- Captain Jack's Famous Ride

- The Old Scouts

- Captain Jack and Buffalo Bill

- Apache War in New Mexico

- Views on Native Americans

- Poet and Entertainer

- Adventurer & Writer

- Final Years

Early Life & Adventures

John Wallace Crawford was born in Carndonagh, Ireland, on March 4, 1847. His parents were from Scotland. His father, John A. Crawford, had to leave Scotland because of his strong opinions. He moved to Ireland. Like many Scots-Irish families, the Crawfords lived in Ulster, northern Ireland, for a time.

When he was fourteen, Crawford moved to the United States from Ireland. He joined other family members in Minersville, Pennsylvania. This area was known for its coal mines. In 1861, his father went to war. Young Crawford started working in the mines to help his family.

At age seventeen, he joined the Forty-eighth Pennsylvania Regiment volunteers. He fought in the last parts of the American Civil War. He was hurt twice. Once at Spottsylvania and again at Petersburg. This was just days before Robert E. Lee gave up at Appomattox. While recovering in a hospital, Crawford learned to read and write. A kind nun taught him. He later used his war stories in his stage shows.

After the war, Crawford worked in coal mines in Centralia, Pennsylvania. His parents moved there with him. His mother, Susie Wallace Crawford, passed away two years later. On her deathbed, she asked John to promise he would never drink alcohol. Crawford kept this promise his whole life. He became one of the few scouts for the U.S. Army who never drank. This promise also became part of his speeches. It helped him become known as someone who spoke out against drinking alcohol.

In September 1869, Jack married Anna Maria Stokes, a local teacher. They moved to Girardville, Pennsylvania, where Jack became the postmaster. He was also a leader in the local miners' union. They had five children. One daughter was named May Cody Crawford, after Jack's friend, William 'Buffalo Bill' Cody.

Black Hills Gold Rush

In 1875, Jack went west for the Black Hills Gold Rush. He later said that adventure books, called dime novels, made him want to go west. For six months, he traveled through the gold camps. He worked as a reporter for the Omaha Daily Bee newspaper. During this time, the people of Custer elected him to their first city council.

In 1876, miners in Custer City formed a group called the "Black Hills Rangers." There were 125 men. Jack was made chief of scouts. This was a special unit of about twelve experienced fighters. Their job was to look for signs of Native Americans and guide settlers through dangerous areas. He likely became "Captain Jack" when he took charge of this group.

War Correspondent

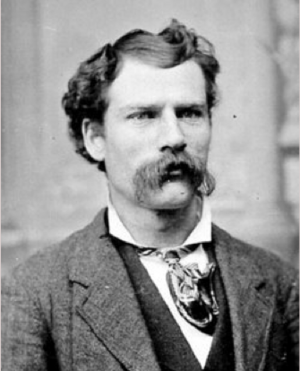

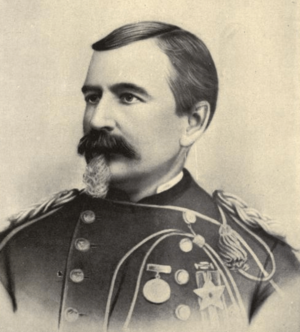

In 1876, Jack worked as a reporter for the Omaha Daily Bee. After General George Armstrong Custer died at the Little Bighorn, Crawford joined General George Crook's army. He became a civilian scout with the Fifth Cavalry on July 22, 1876. Friends gave him gifts like a new rifle and a buckskin suit. The Omaha Daily Bee praised him, saying they hoped he would do well alongside his friend Buffalo Bill.

The Great Sioux War

During the Great Sioux War of 1876, Crawford was a civilian scout with the 5th Cavalry Regiment. He was also a war reporter for the Omaha Bee. He was with General George Crook's expedition. Captain Jack is famous for carrying messages alone on a very dangerous 400-mile route to Fort Fetterman. He also took part in the "Horsemeat March" of 1876. This was one of the hardest marches in American military history.

Crawford played an important part in the Battle of Slim Buttes in 1876. He made a daring ride of over 300 miles in six days. He carried news of the victory to Fort Laramie for the New York Herald. One of his most famous acts was delivering a bottle of whiskey to Buffalo Bill Cody during the campaign.

General Crook's Horsemeat March

Captain Jack traveled for over two weeks to catch up with General Crook's army. He finally reached them on August 8, 1876. An officer later said, "Our campfires were lively after Captain Jack joined us. He sang his songs, told his stories, recited his poems."

Crook's "Horsemeat March" was one of the toughest marches in American military history. Crook's army had about 2,200 men. This included cavalry, infantry, and Native American scouts. Captain Jack Crawford was one of the civilian scouts.

News of General Custer's defeat at the Battle of the Little Big Horn reached the East. The American public was upset and wanted the Sioux punished. Reporters from national newspapers were with General Crook. They sent news of the campaign by telegraph.

On August 26, 1876, General Crook went after the Native Americans. He wanted to show that the U.S. Army would follow its enemies no matter what. The army soon ran low on food. Many men had to eat horsemeat to survive. This march became known as "General Crook's Horsemeat March." The horses and mules were weak from lack of food. Many collapsed in the rain and mud. The soldiers were very tired, wet, and hungry. One officer wrote that he saw men cry because they couldn't go on.

Battle of Slim Buttes

Chief American Horse's Village

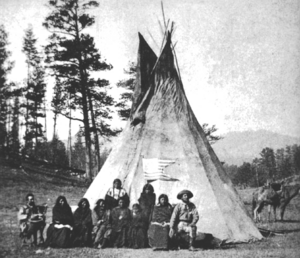

On September 7, 1876, General Crook sent Captain Anson Mills with 150 soldiers. They rode the best horses to get food and supplies from the Black Hills mining camps. Scouts Frank Grouard and Crawford went with Mills. On September 8, Grouard and Crawford found Native American hunters. They soon discovered the village of Oglala Lakota Chief American Horse. The village had 37 lodges and about 260 people. It was hidden in a valley near Reva, South Dakota. About 400 ponies were grazing nearby. The village was sleeping soundly in the cold rain.

The Attack Plan

Captain Mills decided to attack the village at dawn. The plan was to surround the enemy, capture their horses, and defeat the warriors. On the evening of September 8, Captain Mills divided his men into four groups. One group would stay back with the horses. Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka would lead 25 mounted soldiers to charge through the village. They would scare the Native Americans and their ponies. The other soldiers would surround the village and fire as the warriors came out.

The soldiers waited in the cold rain and mist. Before the full plan could happen, the Native American ponies were startled. They stampeded through the village, alerting the people. Since the surprise was lost, Mills ordered an immediate charge. Schwatka, Grouard, Captain Jack, and reporter Strahorn charged into the village. They fired their pistols into the lodges. The Native Americans, surprised, quickly cut their way out of their lodges and fled. Many ran through a swollen creek and into the hills.

Inside the Village

After the Native Americans left, Captain Jack, Strahorn, and about 14 volunteers went into the deserted village. They found a lot of supplies. Chief American Horse's camp was very rich. It had furs, dried meat, and beadwork. The soldiers also captured about 300 ponies.

They found important items from the Battle of Little Bighorn. This included a flag (a guidon) from the 7th Cavalry Regiment. It was attached to Chief American Horse's lodge. They also found the bloody gloves (gauntlets) of Captain Myles Keogh, who had died at Little Bighorn. One lodge had 30 saddles. Another man found $11,000. They also found 7th Cavalry horses, letters, clothing, cash, jewelry, and government weapons.

Messages to General Crook

Captain Mills quickly sent messengers to General Crook, asking for help. Crook was initially angry because Mills had started a fight when he was supposed to get supplies. But he was also pleased with the victory. Crook quickly gathered about 250 men to help Mills. Despite the hard "Horsemeat March," the soldiers were excited for a battle.

Chief American Horse's Defiance

At the start of the attack, Chief American Horse, with three warriors and about 25 women and children, hid in a deep ravine. This ravine was like a cave. Soldiers tried to get them out. Private John Wenzel was killed when he approached the ravine. Other soldiers were wounded.

The Native Americans refused to surrender. They yelled that more Sioux camps were nearby and help would come. Chief American Horse built a dirt wall in front of the cave. He prepared for a strong defense.

General Crook Arrives

General Crook's relief army marched 20 miles in about four and a half hours. They reached Slim Buttes at 11:30 a.m. on September 9. The whole army cheered as they entered the valley. Crook set up his headquarters and a hospital. They found over 5,000 pounds of dried meat, which was a "God-send" for the hungry soldiers.

Crook then focused on getting Chief American Horse and his family out of the ravine. The Native Americans had already killed one soldier and wounded others. The soldiers were angry. Crook ordered his men to fire into the ravine. Hundreds of bullets were fired.

Scout Charles "Buffalo Chips" White, a friend of Buffalo Bill, tried to shoot into the cave. He was immediately killed by the defenders.

Crook was frustrated. He ordered his soldiers to surround the ravine and fire constantly. The Native American women and children inside began to cry loudly. General Crook ordered his men to stop firing. He didn't know women and children were inside. Crook's scouts, Grouard and Pourier, who spoke Lakota, offered safety to the women and children. This offer was accepted. Eleven women and six children came out. But the few remaining warriors refused to surrender. They started fighting again.

Chief American Horse refused to leave. He stayed in the cave with three warriors, five women, and an infant. Crook ordered his soldiers to fire heavily into the ravine. An estimated 3,000 bullets were fired.

Chief American Horse Surrenders

When things quieted, Grouard and Pourier asked American Horse to come out. They promised he would be safe. Chief American Horse, a strong-looking Sioux, came out. He had been shot in the stomach. He said he would surrender if the lives of his warriors were spared. Grouard recognized him. American Horse shook hands with Grouard. When he gave his rifle to General Crook, Crook asked his name. He replied, "American Horse." Some soldiers wanted to shoot him, but no one did. Crook promised that he and his young men would not be harmed.

Two doctors examined Chief American Horse. They tried to close his stomach wound. Chief American Horse bravely held a stick in his teeth to hide his pain. He died stoically. He seemed happy that his family's lives were saved. Dr. McGillycuddy said he was cheerful until the end. American Horse's family was allowed to stay on the battlefield. Crook was kind to them, and they soon felt at home.

Captain Jack's Famous Ride

The Battle of Slim Buttes was the first U.S. Army victory after Custer's defeat at the Little Bighorn. The American public was eager for news. Reporters were with General Crook and sent news by telegraph.

On September 10, 1876, General Crook ordered Frank Grouard, his chief scout, to carry official messages to Fort Laramie. These messages announced the victory at Slim Buttes. Grouard's strict orders were to send the official messages first, then the reporters' messages.

The next morning, Grouard left with Captain Anson Mills and about 75 soldiers. They were going to the Black Hills mining camps to buy food for Crook's hungry army. Captain Jack joined Mills's group, along with reporters Robert E. Strahorn and Reuben Briggs Davenport.

Unknown to Grouard, Davenport wanted an exclusive story for the New York Herald. He offered Captain Jack $500 if he could beat Grouard to the telegraph in Fort Laramie. So, telegraphing the news of the Slim Buttes victory became a race between Frank Grouard and Captain Jack Crawford. It was dangerous because Native Americans were still attacking mining towns.

On September 12, Captain Jack rode into Crook City and quickly bought supplies. That evening, while Grouard slept, Captain Jack rode ahead in the dark to Deadwood. The next day, Grouard learned that Captain Jack had arrived in Deadwood at 6 a.m., gotten a new horse, and left for Custer City. Grouard quickly got fresh horses and caught up with Captain Jack near Custer City.

Grouard asked Captain Jack why he was riding ahead. Captain Jack said he was taking messages for the New York Herald. Grouard told him he was no longer a scout for the army. They agreed to spend the night in Custer City and continue the race the next day. Grouard had changed horses six times. He was so tired he had to be helped off his horse.

On September 16, 1876, Captain Jack reached Fort Laramie at 7:00 p.m. He was nine hours behind a government messenger. Crawford had ridden 350 miles in six days. Still, Crawford got Davenport's messages on the wire five hours before other reporters. On September 18, the New York Herald published Crawford's story. While this adventure cost Captain Jack his job as a military scout, his daring ride made him a national celebrity. Captain Jack proudly told this story to many audiences later in his life.

The Old Scouts

"Old Scouts" like Robert E. Strahorn, Captain Jack Crawford, and Col. Buffalo Bill Cody helped shape how people saw the American West. They often met at "The Wigwam," the home of their friend Major Israel McCreight. There, they could relax and talk about the Old West. Even though they found adventure and fame in the Great Sioux War of 1876, they later regretted it. They didn't like to talk about the war.

Captain Jack's race with Frank Grouard and his dangerous ride made him a national celebrity. Strahorn said his service in the Sioux War brought him great fame. Cody's fight with a Cheyenne warrior helped launch his famous stage career.

Battle of Slim Buttes Reflections

The Battle of Slim Buttes and the destruction of Chief American Horse's village showed the harshness of the U.S. Army's warfare against Native Americans. Villages were attacked at dawn, looted, and burned. The main goal was to destroy their food supplies to make them surrender. This tactic was seen as effective for the army.

Later in life, the Old Scouts didn't want to talk about the Sioux War. Captain Jack and Strahorn were with General George Crook at Slim Buttes and expressed regret. Crawford refused to give details about what he saw at Slim Buttes. He said it hurt him to even think about it.

Strahorn also didn't like to talk about his experiences with Crook's army. Like Crawford, he wished the Slim Buttes event could be erased from history. Buffalo Bill Cody also refused to discuss the killing of Chief American Horse. He just shook his head and said it was too sad to talk about.

Captain Jack and Buffalo Bill

Captain Jack and Buffalo Bill met during the Great Sioux War. In 1876, Crawford left the Black Hills to join Cody on stage. In January 1877, their show, 'The Red Right Hand', was a big hit. It was based on Buffalo Bill's adventures as a scout. Newspapers praised Captain Jack Crawford's acting. They also wrote about his "perilous journey" after Slim Buttes, often making the story even more exciting.

In the summer of 1877, their stage partnership ended. During a horseback fight scene, Captain Jack was injured and blamed Cody for the incident. He was in bed for over two weeks.

Cody and Crawford were very similar. They were good friends but had a difficult relationship. Both were known for being friendly, optimistic, and willing to work hard. They both started working young to help their families. Like Cody, Crawford often left his family for long periods. When Cody's five-year-old son died, Cody told Crawford, who was in the Black Hills. Crawford wrote a poem to comfort his friend.

Apache War in New Mexico

In 1879, Jack moved his family from Pennsylvania to New Mexico. He started scouting for the army again, this time against the Apache nation. He also became a trader at Fort Craig, New Mexico. He started ranching and mining. Crawford served as a U.S. Army scout during Victorio's War in 1880. He and two friends rode deep into Mexico to find the camp of the Apache leader Victorio. After the war, Crawford became a trader at Fort Craig, New Mexico. He made a home for his family there and worked in ranching and mining. Even after the fort closed in 1885, the Crawfords stayed there as caretakers.

Views on Native Americans

Captain Jack, like many army officers, saw reservations as places where Native Americans could learn about American life. He believed Native Americans could change a lot. He thought that owning private land would help them become part of American society. Captain Jack also believed Native Americans would learn new skills and customs at their own speed.

At first, Crawford was angry about Custer and the Little Bighorn. His early shows and poems showed Native Americans as dangerous opponents. But his later shows and poems were more understanding. They focused on feelings that both white people and Native Americans shared. Crawford supported progressive ideas about Native Americans. He even showed mixed-race marriages in his poems and stories. Captain Jack promoted education for Native Americans. He was against sending children to boarding schools far from their homes. He believed education should be close to home, "under the eyes of the parents."

From 1889 to 1893, Crawford worked for the U.S. Justice Department. He investigated illegal alcohol sales on Native American reservations in the West.

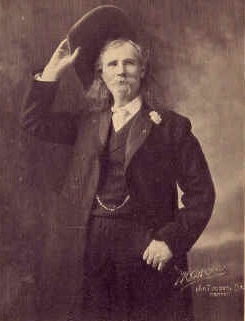

Poet and Entertainer

From 1893 to 1898, Crawford became famous as an entertainer called the "Poet Scout." Captain Jack was a popular speaker and performer across the U.S. He gave talks about the West and the Sioux Wars. He also encouraged people not to drink alcohol. Sometimes he spoke to thousands of people. He would sometimes give three shows in one day.

Captain Jack was one of many speakers who benefited from Americans' love for lectures. People in the 1890s wanted to learn more. Thousands went to lecture halls and summer events called Chautauquas. Jack traveled across the country. He spoke to veterans, schoolchildren, college students, and many middle-class Americans.

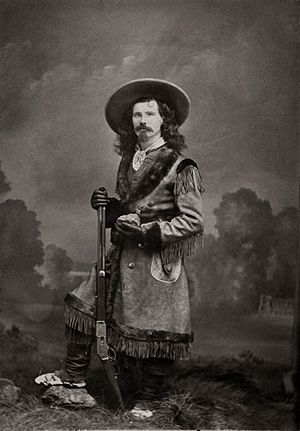

Captain Jack's style, charm, and poetry made him a popular celebrity. He would come on stage dressed in buckskin, with a wide-brimmed hat and long curly hair. With a rifle and a pistol, he looked like a mythical hero of the American Wild West. His shows were like a "frontier monologue." One reporter said he "held his audience spell-bound for two hours." His shows presented the West as a place of adventure, opportunity, and freedom. Crawford blamed "dime novels" (cheap adventure books) for leading young men into crime and poverty. He said they caused tragedies during the Black Hills gold rush. Youngsters were lured west by stories, only to die from the cold or in fights with the Sioux.

Adventurer & Writer

Crawford's experiences in the Black Hills greatly affected his later life. He learned about gold mining and realized that money was needed for development. For the rest of his life, he was very interested in mining. In the spring of 1878, he traveled to the gold fields in the Cariboo Region of British Columbia.

Crawford was a very active writer. He published seven books of poetry. He also wrote over one hundred short stories and four plays. Captain Jack's writings about frontier life were known for showing the real dangers of pioneer life. Many of his books and poems are still performed today. Some became songs, like "The Death of Custer" and "Rattlin' Joe's Prayer." His poem "Only a Miner Killed" is said to be the basis for Bob Dylan's song "Only a Hobo."

Final Years

From 1898 to 1900, Captain Jack spent two years in the Klondike, looking for gold without success. When he returned to the United States, he went back to lecturing. For the next ten years, he traveled the country performing.

Captain Jack separated from his family later in life. He moved back east to Woodhaven, Long Island, New York. He died of Bright's disease (a kidney illness) on February 27, 1917. Newspapers across the nation reported his death. One writer called him "a real scout, and a real poet—a man with a warrior's soul and the heart of a woman."

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |