Judah Leon Abravanel facts for kids

Judah Leon Abravanel (born around 1460 in Lisbon, died around 1530, possibly in Naples), also known as Leo the Hebrew, was a Portuguese-Jewish thinker, doctor, and poet during the Middle Ages. His most famous book, Dialogues of Love, was a very important philosophical work of his time.

Contents

Biography

The Abravanel family was very well-known among Jewish families in the Middle Ages. They often served in public roles for the court of Castile. Judah was the son of Isaac Abarbanel, a famous Bible expert, statesman, and financial advisor. Isaac was born in Lisbon in 1437 and worked for King Afonso V of Portugal.

However, in 1481, King Afonso V died. Isaac was suspected of plotting against the new king, João II. Because of this, he had to leave Portugal quickly without his family. He eventually settled in Toledo, where his family later joined him.

Spain was then ruled by the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. They wanted to unite Spain and conquer the Muslim kingdom of Granada. Isaac Abravanel became a financial advisor to their court. In 1484, Judah joined his father, working as a personal doctor for the royal family.

The year 1492 brought a huge change for all Jews in Spain, including the Abravanel family. Isabella and Ferdinand ordered all Jews to either convert to Christianity or leave Spain. Isaac begged them to change their minds, but it was no use. He planned to move his family to Naples, Italy.

There was also a plan to take Judah's son to force the family to convert and stay in Spain. Judah tried to send his son to Portugal with a nurse, but the king's order led to his son being taken and baptized. This event deeply hurt Judah and his family. It caused him great sadness throughout his life and he wrote about it years later.

The Abravanel family chose to leave Spain rather than convert. This was a difficult choice, as Jews were not welcome in many parts of Europe. They also were not allowed to take much money with them. Isaac and his family first planned to go to the Ottoman Empire, but they settled in Naples. Isaac became a financial advisor to the King of Naples, Ferdinand I of Naples. The family was respected in Naples until 1494, when Charles VIII of France invaded. The Neapolitan royal family, along with Isaac, fled to Sicily.

Meanwhile, Judah moved to Genoa, where he studied and likely started writing his Dialoghi. He may have moved to Barletta in 1501 to serve Frederick IV of Naples. Then, in 1503, he went to Venice to rejoin his father. Other accounts say he stayed in Naples until 1506. While in Naples, Judah became the doctor for the Spanish viceroy, Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba.

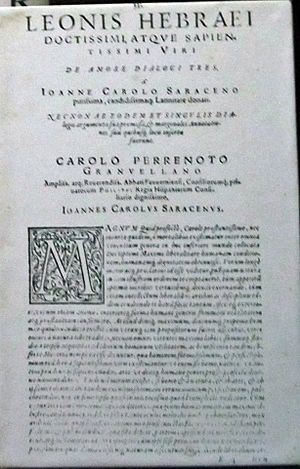

By 1506, Spain took control of southern Italy. Judah left Naples for Venice, where he focused on philosophy until 1507. Not much is known about his life after this time. His famous work, Dialoghi d'amore, was likely written around 1501-1502. When his friend Mariano Lenzi found the manuscript and published it in Rome in 1535, Judah had already passed away.

Some people claimed that Judah converted to Christianity later in his life. However, this claim seems to be false. A Venetian publisher of his book in 1541 and 1545 added a note saying he had converted. But this note was not in the first edition or later ones. It was probably added to help sell the book to people who disliked Jews. Judah's own writings in Dialoghi show he remained true to his Jewish faith. He wrote that the book was based on "Hebrew truth" and for "all of us who believe in the holy law of Moses."

Influences on His Thinking

Judah traveled a lot and met many important thinkers, known as humanists, in Italy. He also knew people at the Neapolitan Court. Some believe he met Giovanni Pico della Mirandola in Florence. He might have also known Elia de Medigo and Yohanan Alemanno, who were Jewish writers. Other thinkers he might have met include Giovanni Pontano and Marsilio Ficino.

Many humanists around Judah were interested in the topic of Love. Famous works like Marsilio Ficino's comments on Plato’s Symposium and Girolamo Benivieni's Canzone d’amore were written around his time. Judah's Dialoghi is considered one of the best works on this topic from that period.

Like other humanist works, Dialoghi was greatly influenced by the ideas of Plato and Aristotle. Judah used Platonic ideas, but he filtered them through his Jewish background. His ideas were shaped by Jewish scholars like Solomon ibn Gabirol and Maimonides. He was also influenced by the Greek spirit of the Renaissance. The idea of reaching for an ideal of beauty, wisdom, and perfection is central to his work.

Dialoghi d'amore (Dialogues of Love)

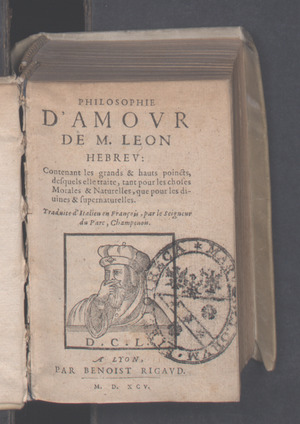

The Dialoghi was a very popular book. It had at least five editions published in just twenty years. It was first published in Italian and then translated into French, Hebrew, and Latin. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega made one of its three Spanish translations. Judah's Dialoghi was one of the first important philosophical books written in a common language, not Latin.

There is some debate about what language Judah first wrote the book in. Some think it might have been written in Judeo-Spanish, a mix of Hebrew and Castilian Spanish. A manuscript in the British Library shows a Spanish translation written with Hebrew letters. This was once thought to be the original, but it is now believed to be a copy of a later Spanish translation. This translation was likely made to highlight Judah's Jewish identity and to help Spanish-speaking Jewish communities.

In his Dialoghi d'amore, Judah Abravanel tries to explain love using philosophical ideas. He structures the book as three conversations between two characters: Philo, who represents love, and Sophia, who represents wisdom. Their names together, Philo+Sophia, mean "philosophy."

First Dialogue: Love and Desire

The first dialogue is called "Philo and Sophia on Love and Desire." It explores the differences between love and desire. Sophia believes love and desire are separate. But Philo argues that they mix in things we enjoy. He says desire wants to unite with its object, and love enjoys that union. When love and desire meet, objects can be useful, pleasant, or good. Useful objects are not loved and desired together. Pleasant objects are loved and desired at the same time. Good objects have no limit to love and desire.

Sophia then asks Philo to explain the difference between loving God and loving friends. Philo says God is the source of all good in the world. But as humans, we cannot fully understand or love God completely.

The next topic is happiness. They decide that happiness comes not from having things, but from wisdom and virtue. Wisdom is not knowing everything, but it can be found in knowing God.

Sophia then asks Philo to explain knowledge and love of God. He says wisdom comes from loving God and is the source of human happiness. Philo then tries to define his love for Sophia. He says that physical closeness can increase love. He adds that love comes from Reason, which drives us to seek the beloved. Philo suggests they end the discussion for the night, but Sophia wants to continue.

Second Dialogue: Universality of Love

The second dialogue, "Philo and Sophia on the Universality of Love," suggests that love is a main force in all life. It describes how love works in human lives.

Sophia asks Philo to explain where love comes from and how it is everywhere.

Third Dialogue: Origin of Love

The third and longest dialogue, "Philo and Sophia on the Origin of Love," discusses God's love. It explains how God's love covers everything, from the smallest creatures to the heavens. It is the "cohesion of the universe." This dialogue also talks about beauty and the soul, using ideas from Plato. It is considered the most important part of the book for its artistic beauty.

In this dialogue, Philo and Sophia meet again. Philo apologizes for not recognizing Sophia because her beauty amazed him. He then compares the soul and the intellect. The intellect is purely spiritual. The soul is partly spiritual and partly physical, always moving between the body and mind.

Philo then explains that love must have been created, because it needs both a lover and a beloved. The first love and cause of the universe is God's love for Himself. So, love was born when the universe was created.

The birthplace of love, he says, was the angelic world. This world is the most perfect of all created things. It has the most perfect knowledge of the divine beauty it lacks.

Philo also answers who the parents of love were. He talks about the story of Cupid and the ancient idea of Androgynous beings. He also mentions the creation of Adam and Eve. The universal father of all love is beauty, and the universal mother is knowing beauty along with lacking it. Beauty is necessary for all love. God is the most beautiful, and His wisdom is the highest beauty. The goal of all love is pleasure, which is the desire for union with the beloved. The goal of the universe's love is union with divine beauty.

However, Philo points out that his own love brings him only sadness. This is because Sophia will not return his feelings. She only believes in the love of the intellect. She asks him to tell her about the effects of love, wanting to know the dangers he might lead her into. The lovers then part, and their next meeting is not described.

Dialoghi d'amore was an important work in Spanish culture. It brought new ideas from the Renaissance to Spain. It showed how human love can be spiritual, connecting it to divine love. It suggested that people should go beyond physical union to connect minds and souls.

Miguel de Cervantes mentions Dialoghi d'amore in the introduction to his famous book, Don Quixote.

See also

In Spanish: León Hebreo para niños

In Spanish: León Hebreo para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |