Karoo Ashevak facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Karoo Ashevak

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1940 Kitikmeot Region

|

| Died | October 19, 1974 (aged 33–34) |

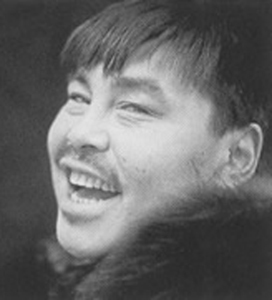

Karoo Ashevak (Inuktitut: ᑲᕈ ᐊᓴᕙ) (1940 – October 19, 1974) was an Inuk sculptor. He lived a traditional hunting life in the Kitikmeot Region of the central Arctic. In 1960, he moved to Spence Bay, which is now Taloyoak, Nunavut.

Karoo started his art career in 1968. He joined a government-funded program that taught carving. He mainly used fossilized whale bone for his sculptures. During his life, he made about 250 pieces of art. His work often showed themes of shamanism and Inuit spirituality. He created fun sculptures of people, angakuit (shamans), spirits, and Arctic animals.

In 1970, Karoo's sculptures won third prize in a big competition in Yellowknife. He became a well-known artist after his own art show in New York in 1973. Unlike other Inuit carvings, Karoo's art looked more modern. It appealed to many different people, not just those who collected Inuit art.

Karoo's sculptures were shown in galleries all over the world. These included places like Washington, D.C., Montreal, Winnipeg, and Toronto. His art was also bought and sold a lot at auctions. Karoo died in October 1974 in a house fire. Even though his career was short, he helped Inuit sculpture grow. He showed an amazing world of spirits and shamanistic ideas through his art.

Contents

Karoo Ashevak's Early Life

Karoo Ashevak was born in 1940 in the Kitikmeot Region of the central Arctic in Nunavut. Like many young Netsilik people, he lived a traditional Inuit life. He learned hunting skills to support himself. But Karoo grew up when new settlements were changing the Inuit way of life.

In the past, Netsilik people lived in small groups. They moved around as hunters. When they moved to Spence Bay, they had to change their way of life. They started living in houses and having steady jobs. Karoo and his wife Doris moved to the settlement in 1968.

Around this time, people in Ottawa became very interested in Inuit carvings. So, the government started a carving program in Spence Bay. A sculptor named Algie Malauskas was hired to teach Inuit people how to carve. Karoo joined the program because hunting no longer provided enough money. Carving was a good way to earn a living.

Karoo officially started his art career in 1970. He entered the Centennial competition in Yellowknife. His sculptures, Bird and Drum Dancer, won third prize and an honorable mention. In 1972, Avrom Isaacs gathered Karoo's works. He put on a solo show at the Inuit Gallery in Toronto. This show was very successful. About 30 of Karoo's sculptures were popular and sold well.

However, this show did not make Karoo famous everywhere. His reputation grew strong after his exhibition at the American Indian Art Centre in New York in 1973.

Karoo Ashevak's Art Career

In 1968, Karoo Ashevak settled in Taloyoak. His art career began with a government-sponsored arts and crafts program. By the early 1970s, his art style became known as "expressionistic" in the Kitikmeot area. His works were inspired by stories his father told him as a child.

Many of his sculptures have wide noses, open mouths, and uneven eyes. People admire his art for being so original and unique. Some people loved his work, while others found it a bit strange. Most of his art was created between 1971 and 1974.

During this time, he was not yet famous in the art world. Still, he had several shows where his art was popular and sold a lot. He was first noticed in Yellowknife in 1970. This was when he entered the Centennial competition. It was organized by the Canadian Eskimo Art Council.

Karoo did not become widely known until later in his career. He is now seen as an important artist in Canadian Inuit art. In the spring of 1972, Avrom Isaacs used Karoo's sculptures. He put on a solo show at the Inuit Gallery in Toronto. This show was successful, but it did not make him famous outside of Inuit art circles.

Finally, in January 1973, his show at the American Indian Art Centre in New York made him famous. This show built his reputation in eastern U.S. and Canada. This was the peak of his career, just one year before he passed away.

Materials Karoo Ashevak Used

In the 1970s, Karoo Ashevak mostly used old whale bones for his art. During his time as an artist, whale bones were brought to his community by plane. This was because whale bone was hard to find there. Many other carvers also wanted this material for their art.

Long ago, people in Taloyoak used bones to make tools and weapons. But when carving became popular, whale bone became the main material for sculptures. Both the ancient Thule people and later European whalers left behind many whale bones. These old bones had been exposed to the harsh Arctic weather for a long time. This changed their qualities, like how dense they were and their color.

Whale bones needed to be aged for about 50 to 100 years before they were good for carving. If the bone was too new or not fully dry, it might smell or shrink while being carved.

Whale bone comes in many colors, from white to cream, brown, or almost black. It can also be very dense or very fragile. The material might even change its density, which meant artists needed great skill. Sometimes, bone could become so hard it was almost impossible to carve. Whale bone might also crack or split before, during, or after carving. Cracks that happened while carving could be part of the finished art. But splits that appeared later often ruined the piece.

Karoo might have chosen whale bone because other materials were limited. Or he might have preferred lighter materials over heavy ones like stone or ivory. Even though he mainly used fossilized whale bone, Karoo often added other local materials. These included stone, caribou antler, baleen, and walrus ivory.

Karoo would first think of an idea for a sculpture. Then he would choose the material to use. He used the natural shapes of the bone. He changed the material to fit his ideas and the theme of his art. He also often rearranged bones from different parts of the whale. He cared more about his design than sticking to one piece of bone. For example, Karoo often used whale baleen to make the eyes and mouths of his sculptures.

Karoo Ashevak and the Art World

According to Leon Lippel, people loved Karoo Ashevak's sculptures when they first saw them. Between 1972 and 1974, Karoo had several successful art shows. His works sold very well in the art market. Karoo's sculptures had a message that everyone could understand. This was very different from most Inuit art. Max Wheitzenhoffer from the Gimpel-Wheitzenhoffer gallery said he "never looked at Ashevak’s pieces as Eskimo art."

Most Inuit sculptures told stories. They showed legends, events, or daily life that Inuit communities knew well. But Karoo's sculptures were different. Each of his pieces showed a unique being. They did not refer to specific myths or stories. Because of this, Karoo's art could connect with people who knew nothing about Inuit culture. It attracted people just for its beauty.

Karoo's early shows had two special features. First, his sculptures were very popular with people who did not usually collect Inuit art. Second, people were amazed by Karoo's work. They reacted with great excitement right away. Karoo became well-known in Canada and the United States. This happened soon after his shows at the Inuit Gallery of Toronto (1972) and the American Indian Arts Centre in New York (1973). Usually, it takes time for people to like a new art style. But they loved Karoo's work right away.

Works and Shamanism

Karoo Ashevak's sculptures show a fantasy world of spirits and supernatural beings. These figures are full of strong feelings. His sculptures often have wide eyes, open mouths, unusual body shapes, and carved lines. These features are directly linked to Inuit religion (shamanism).

Angakuit (shamans) are people with special powers. They can act as a link between the human world and the spirit world. Shamanism is based on the idea that a spirit can exist in every living thing. These spirits can take different forms. Some spirits are kind to humans. They help angakuit do special tasks. Other spirits are evil. They might attack humans and bring bad luck to the community. Angakuit could protect people from evil spirits. They did this by getting help from spirits often seen as polar bears, birds, and walrus. Karoo showed many helping spirits in animal forms. Examples include Bear (1973), Flying Walrus (1972), and a strange four-legged creature with wings.

Birds were another favorite subject for Karoo's sculptures. Some birds in his art have prey in their mouths. Others have unusual features, like human arms (1972). Some even show a human changing into a bird. Birds are connected to the angakkuq's magical flights. In the Netsilik tradition, angakuit could turn into birds. They could travel to all parts of the universe. During these magical journeys, angakuit would fly into the sky, to the land of the dead, and even to the homes of ancient Inuit gods. Karoo showed these shamanistic flights in his sculptures Flying Figure (1971) and Shaman (1973). In these works, the angakuits’ bodies are shown in a flying position.

Karoo did not give titles to most of his works. But one of the few sculptures that had a title was about shamanism. In Inuit culture, a person needs to train to become an angakkuq. The person learns from an elder. This training helps them gain the skills and powers needed for their future role. At the end of the training, an elder angakkuq would pass on their power. They would place their hands on the young shaman's head. Karoo's work, Coming and Going of the Shaman (1973), shows this transfer of powers. This sculpture has two heads of different sizes that share one body. The angakkuq with the larger head is fading away. He is passing his powers to the angakkuq with the smaller head.

Karoo's ideas for his art also came from dreams, childhood stories, and hunting scenes. Dreams were very important in Inuit culture, especially in the Netsilik community. Karoo's sculpture, Drum Dancer, was inspired by his dream of a man with three arms. Other visual ideas in Karoo's art included eyes of different sizes and shapes. In shamanistic belief, certain spirits acted as the angakkuq's eyes. They could fly far away and tell the angakkuq what they had seen. Also, Karoo's use of carved lines was linked to the Thule culture. In his sculptures Bird from 1970 and 1971, carved lines show the birds' skeletons. This is a common feature in shamanism.

Karoo Ashevak's Personal Life

Karoo Ashevak was known for being very open about his feelings. This was unusual for Inuit adults. They valued Ihuma, which meant being able to control emotions. Ihuma was an important part of their personality. Adults showed Ihuma by hiding their joy or anger in public. However, Karoo freely showed his emotions. Sometimes, he even showed strong or angry behaviors.

Karoo loved making carvings. He was very proud of his work. He knew how much his sculptures were worth. He set their prices fairly himself. Carving was Karoo's main way to earn money. But money was not the only reason he kept creating. Karoo's favorite part of sculpting was adding the final touches. These details made each piece special. Karoo respected the uniqueness of carvings. He got upset when other sculptors copied his work. He did not know how to deal with people who imitated his art.

In August 1974, Karoo's life took a sad turn. His adopted son, Lary, died. On October 19 of the same year, Karoo and his wife Doris both died in a fire that destroyed their home.

Karoo Ashevak's Achievements

Karoo Ashevak became very well-known in his community and nearby areas. His art inspired many carvers in the Kitikmeot region. Even though he made only about 250 sculptures in his short career, his works have been in many shows. They are still widely collected and sold today. His art is also found in many company and museum collections.

He had solo art shows in Toronto, Montreal, and New York. When he was first officially noticed in 1970, he won third prize and an honorable mention. This was for his sculptures Bird and Drum Dancer at the Centennial competition in Yellowknife. This was the start of his successful career.

Karoo's early shows between 1972 and 1974 were very successful. Many of his works were wanted and sold, even though he was not yet famous. Two things made these shows special. One was the type of buyers. The sculptures were popular with both Inuit and non-Inuit art collectors. They also appealed to people who did not usually buy art. The other special thing was how the audience reacted. People were immediately amazed by his work. This was especially true at the Inuit Gallery in Toronto and the American Indian Arts Centre in New York.

Max Weitzenhoffer, a theater producer, called Karoo one of the best Canadian sculptors of his time. He saw Karoo's work as special and different from other Inuit artists. He believed Karoo's art was accepted by everyone and appealed to many people. Scholar George Swinton compared Karoo to Henry Moore. Moore is a famous English artist known for his sculptures.

Exhibitions

- 1972: "Eskimo Fantastic Art", University of Manitoba, Winnipeg

- 1973: "Cultures of the Sun and the Snow: Indian and Eskimo Art of the Americas", Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Quebec

- 1973: "Karoo Ashevak: Spirits", at the American Indian Arts Centre, New York City

- 1973: "Karoo Ashevak Whalebone Sculpture", Lippel Gallery, Montreal

- 1973: "Spirits", Franz Bader Gallery, Washington, D.C.

- 1977: "Karoo Ashevak", Winnipeg Art Gallery, Manitoba

- 1977: "White Sculpture of the Inuit", Simon Fraser University Art Gallery, Burnaby, B.C.

- 1977: "Karoo Ashevak (1940-1974): Sculpture", Upstairs Gallery, Winnipeg

- 1978: "The Coming and Going of the Shaman: Eskimo Shamanism and Art", Winnipeg Art Gallery, Manitoba

- 1980: "Whalebone Carvings and Inuit Prints", Memorial University of Newfoundland Art Gallery, St. John's

- 1983: "Inuit Masterworks: Selections from the Collection of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada", McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinberg, Ontario

- 1985: "Uumajut: Animal Imagery in Inuit Art", Winnipeg Art Gallery, Manitoba

- 1986: "Contemporary Inuit Art", National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- 1988: "Building on Strengths: New Inuit Art from the Collection", Winnipeg Art Gallery, Manitoba

- 1988: "In the Shadow of the Sun: Contemporary Indian and Inuit Art in Canada", Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec

- 1990: "Arctic Mirror", Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec

- 1990: "Inuit Art From the Glenbow Collection", Glenbow Museum, Calgary

- 1994: "Transcending the Specifics of Inuit Heritage: Karoo in Ottawa", at the National Gallery of Canada

- 1999 – 2000: "Carving and Identity: Inuit Sculpture from the Permanent Collection", National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- 1999: "Iqqaipaa: Celebrating Inuit Art, 1948 - 1970", Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec

Collections

Museums and galleries that permanently display his works:

- Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto)

- Canadian Museum of Civilization (Gatineau, Quebec)

- Glenbow Museum (Calgary, Alberta)

- Heard Museum (Phoenix, Arizona)

- McMichael Canadian Art Collection (Kleinburg, Ontario)

- Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Quebec), Museum of Anthropology (University of British Columbia, Vancouver)

- Museum of Inuit Art (Toronto, Ontario)

- Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre (Yellowknife, Northwest Territories)

- Quebec Museum of Fine Arts (Quebec City)

- Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian (Washington, D.C.)

- University of Alberta (Edmonton, Alberta)

- Winnipeg Art Gallery (Manitoba)

- National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa)

- Lorne Balshine Inuit Art Collection at the Vancouver International Airport (Vancouver, B.C.)

- TD Gallery of Inuit Art at the Toronto-Dominion Centre (Toronto, Ontario)

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |