Kingdom of Albania (medieval) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Albania

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1272–1368 | |||||||||||||||

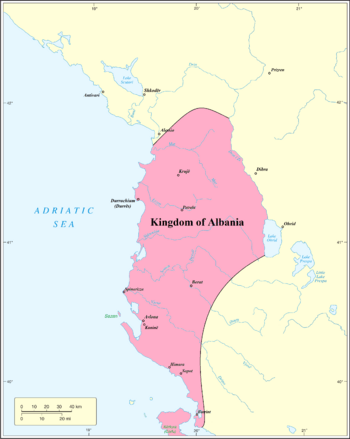

Kingdom of Albania at its maximum extent (1272-1274)

|

|||||||||||||||

| Status | Personal union with the Angevin Kingdom of Sicily/Naples / Kingdom of Albania (medieval) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Durazzo (Dyrrhachium, modern Durrës) | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| King, Lord and later Duke | |||||||||||||||

|

• 1272–1285

|

Charles I | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1366–1368

|

Louis | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | ||||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

1272 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1368 | ||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | AL | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Albania was a medieval state. It was created by Charles of Anjou in February 1272. He took control of Albanian lands from the Byzantine Empire. These lands were located around Durazzo (modern Durrës) and stretched south along the coast to Butrint.

Charles tried to expand his kingdom towards Constantinople. However, his efforts failed during the Siege of Berat (1280–1281). The Byzantines then fought back, pushing Charles's forces out of the inner parts of Albania by 1281. An event called the Sicilian Vespers further weakened Charles's power. His kingdom in Albania shrank to a small area around Durazzo. The Angevins held onto Durazzo until 1368. That year, Karl Thopia captured the city. Later, in 1392, Karl Thopia's son gave the city to the Republic of Venice.

Contents

History of the Kingdom

How the Kingdom Started

In 1253, during a conflict between the Despotate of Epirus and the Empire of Nicaea, a local lord named Golem of Kruja first sided with Epirus. He tried to stop Nicaean forces from entering Devoll. However, the Nicaean leader, John Vatatzes, convinced Golem to switch sides. A new agreement promised Golem's lands would remain independent.

Later, the Nicaeans took control of Durrës in 1256. They tried to rule the area of Arbanon directly, which went against their promises. This made local Albanian leaders angry, and they revolted. Michael II, the ruler of Epirus, also broke his peace treaty with Nicaea. He attacked cities like Dibra and Ohrid with Albanian help.

Meanwhile, Manfred of Sicily saw an opportunity. He invaded Albania, capturing Durrës, Berat, Vlorë, and other coastal areas. Michael II then made peace with Manfred and became his ally. Manfred respected the local Albanian nobles and even included them in his government. He appointed Philippe Chinard as the general-governor of his Albanian lands.

Charles of Anjou Takes Control

After Manfred's defeat in 1266, Charles of Anjou gained rights to Manfred's lands in Albania. Local nobles refused to give these lands to Charles.

After the Eighth Crusade failed, Charles focused on Albania again. He contacted local Albanian leaders through Catholic priests. In February 1272, Albanian nobles and citizens from Durrës met Charles. He signed a treaty with them and was declared King of Albania. He promised to protect them and respect their old rights. This created the Kingdom of Albania, linked to Charles's Kingdom of Sicily.

Charles then sent supplies to Durrës and Vlorë, planning to attack Constantinople. This worried the Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos. Michael tried to convince Albanian nobles to stop supporting Charles. However, Charles's plans were put on hold by Pope Gregory X, who wanted peace to unite the churches and start a new crusade.

Charles of Anjou soon imposed strict military rule in Albania. He took away the promised independence and added new taxes. Lands were taken and given to his own nobles. Albanian nobles lost their government roles. To ensure loyalty, Charles even took sons of local nobles as hostages. This made many Albanians unhappy, and some started talking with the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII, who promised to restore their old rights.

Byzantine Empire Fights Back

Since Charles's plans were stopped by the Pope and there was unrest in Albania, Michael VIII seized the chance. In late 1274, Byzantine forces, helped by local Albanian nobles, captured the important city of Berat and later Butrint. By November 1274, Durrës was under siege. The Byzantines also captured the port of Spinarizza. This left Durrës, Krujë, and Vlora isolated, only able to communicate by sea. Charles still held the island of Corfu.

Michael VIII also made a deal with the Pope to unite the churches in 1274. This made Pope Gregory X forbid Charles from attacking Michael VIII. So, Charles had to sign a truce with the Byzantines in 1276.

Angevin Counterattack

The Byzantine presence in Butrint worried Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas, the ruler of Epirus. He allied with Charles of Anjou. In 1278, Nikephoros I's troops captured Butrint. In March 1279, he became Charles's loyal follower and gave him the castles of Sopot and Butrint. Nikephoros I even sent his own son as a hostage to Charles.

Charles also started making alliances with the kings of Serbia and Bulgaria. He tried to get support from local Albanian nobles. He even released some Albanian nobles from prison who had been accused of helping the Byzantines. Among them was Gjin Muzaka, whose family lands were near Berat. They were freed but had to send their sons as hostages to Naples.

In August 1279, Charles appointed Hugo de Sully as his main commander in Albania. A large counterattack was planned. Many supplies and soldiers were sent to de Sully, who made Spinarizza his base. The main goal was to retake Berat. However, Pope Nicholas III stopped Charles from attacking the Byzantine Empire. But when Pope Nicholas III died in August 1280, Charles saw his chance. In December 1280, Angevin forces surrounded Berat and began to besiege its castle.

Byzantine Empire Fights Back Again

The Byzantine Emperor hoped the Pope would stop Charles. After Pope Gregory X died, later Popes continued to support church unity, limiting Charles's actions. However, in February 1281, Charles managed to get a French Pope elected. This new Pope blessed Charles's attack as a new crusade.

Despite this, Michael VIII sent help to Berat. The Byzantine army arrived in March 1281. They avoided direct battles, focusing on ambushes. They captured the Angevin commander, Hugo de Sully, in an ambush. This caused panic among his troops, leading to their defeat. The Angevin army lost most of its forces. The Byzantines continued to advance, besieging Vlorë, Kaninë, and Durrës, but they couldn't capture them. Albanian nobles in the Krujë region allied with the Byzantine Emperor, who gave them special rights.

Charles's Plans and the Sicilian Vespers

Treaty of Orvieto

The failure at Berat convinced Charles that a land invasion of the Byzantine Empire wouldn't work. He decided to plan a sea attack. In July 1281, he allied with Venice through the Treaty of Orvieto. The goal was to remove Michael VIII from power and bring the Greek Orthodox Church under the Pope's control. The real aim was to bring back the Latin Empire under Charles's rule and restore Venice's trade rights in Constantinople.

The treaty stated that Charles and Philip of Courtenay (the Latin emperor) would provide 8,000 soldiers and ships. Venice would provide forty warships. The invasion fleet was to sail from Brindisi by April 1283.

Sicilian Vespers

On March 30, 1282, a major uprising against French forces began in Sicily. This event is known as the Sicilian Vespers. The violence lasted for weeks, and Charles's fleet, gathered for the Byzantine invasion, was destroyed in Messina harbor. Charles tried to stop the revolt, but when Peter III of Aragon landed in Sicily in August 1282, it was clear Charles could no longer attack Byzantium. By September 1282, the Angevin family lost Sicily forever. Charles's son, Charles II of Naples, was captured by the Aragonese. Charles I died in January 1285, leaving his lands to his imprisoned son. Charles II was released in 1289.

The Kingdom Shrinks and Recovers

The Angevins held onto Kaninë, Durrës, and Vlorë for a few more years. However, Durrës fell to the Byzantines in 1288. In the same year, Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos renewed special rights for Albanians in the Krujë region. Kaninë castle was probably the last to fall to the Byzantines around 1294. Corfu and Butrint remained under Angevin control until at least 1292. In 1296, the Serbian king Stephen Milutin took Durrës.

Durrës is Retaken

Even though the Angevins lost most of their Albanian lands, they still claimed rights to the Kingdom of Albania. Charles II inherited these rights after his father's death in 1285. In 1294, Charles II gave his rights to his son, Philip I, Prince of Taranto. Philip married the daughter of the Epirote ruler, renewing an old alliance. His plans to regain lands were paused when he was captured in 1299.

After his release in 1302, Philip claimed his rights again. He gained support from local Albanian Catholics, who preferred a Catholic ruler over Orthodox Serbs and Greeks. He also had the support of Pope Benedict XI. In 1304, the citizens and nobles of Durrës expelled the Serbs and submitted to Angevin rule. Philip and his father, Charles II, restored the old rights promised to Durrës. In 1305, Charles II granted more tax breaks to the people of Durrës.

The Kingdom of Albania under Philip of Taranto was mostly limited to the area around modern Durrës District. There were talks to trade the Kingdom of Albania for other lands, but these failed in 1316.

Duchy of Durazzo

When Philip of Taranto died in 1332, his lands were divided among the Angevin family. The rights to the Duchy of Durazzo (Durrës) and the Kingdom of Albania went to John of Gravina. After John's death in 1336, his son Charles, Duke of Durazzo inherited these lands.

During this time, different Albanian noble families grew stronger. One important family was the Thopia family in central Albania. The Serbs were pushing into the area, so Albanian nobles found allies in the Angevins. Alliances with Albanian leaders were very important for the safety of the Kingdom of Albania. The Thopias and the Muzaka family were key allies. Charles had some success against Serb forces in central Albania in 1336–1337.

Final Years

The pressure from the Serbian Kingdom grew, especially under Stefan Dušan. By 1346, most of Albania was under Dušan's rule. In 1348, Charles, Duke of Durazzo, was executed. His cousin, Philip II, Prince of Taranto, inherited his rights to Albania.

After Dušan's death, his empire broke apart. In central Albania, the Thopia family, led by Karl Topia, claimed rights to the Kingdom of Albania. Karl Thopia took Durrës from the Angevins in 1368 with the support of its citizens. In 1376, Louis of Évreux, Duke of Durazzo briefly recaptured the city, but Thopia took it back in 1383.

In 1385, Durrës was captured by Balša II. Thopia asked for help from the Ottomans, and Balša's forces were defeated in the Battle of Savra. Thopia recaptured Durrës that same year and held it until his death in 1388. His son, Gjergj, Lord of Durrës, inherited the city. In 1392, Gjergj surrendered Durrës and his lands to the Republic of Venice.

How the Kingdom Was Governed

The Kingdom of Albania was separate from the Kingdom of Naples. It had its own government in Durrës, focused on military matters. The main leader was the captain-general, who acted like a viceroy (a ruler acting for the king). These officials were called capitaneus et vicarius generalis and led the army. Local forces were commanded by a marescallus in partibus Albaniae.

Money from royal sources, especially from salt production and trade, went to the kingdom's treasurer (thesaurius). The port of Durrës and sea trade were very important. The port was managed by a prothontius, and the Albanian fleet had its own captain. Other government jobs were created under the viceroy.

As the kingdom's territory shrank, the captain-generals lost power. They became more like governors of Durrës than representatives of the king.

Local Albanian lords became more important to the kingdom's survival. The Angevins included them in their military. When Philip of Taranto returned in 1304, an Albanian noble, Gulielm Blinishti, was made head of the Angevin army in Albania. Later, Andrea I Muzaka took this role. From 1304 onwards, the Angevins also gave Western noble titles to local Albanian lords.

Even though the Angevins tried to create a strong central government, they allowed Albanian cities a lot of freedom. In 1272, Charles of Anjou himself recognized the old rights of the Durrës community.

Religion in the Kingdom

The area of the Kingdom of Albania had a mix of religious influences. Both Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy were present. The creation of the kingdom strengthened the influence of Catholicism. This led to more people converting to the Catholic faith, not just in Durrës but also in other parts of the country.

The Archbishopric of Durrës was a very important religious center. After the Great Schism in 1054, it remained under the Eastern Orthodox Church. However, after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1204, things changed. A Catholic archbishop was chosen for Durrës in 1208. Later, after Manfred captured the city in 1258, it became a Catholic center again.

The new Catholic kingdom in 1272 helped the Pope's plans to spread Catholicism in the Balkans. Helen of Anjou, who was married to the Serbian King Stefan Uroš I and was Charles of Anjou's cousin, also supported this. She helped build about 30 Catholic churches and monasteries in North Albania and Serbia. New Catholic bishoprics were created, especially in North Albania, with her help.

Durrës became a Catholic archbishopric again in 1272. Other areas of the kingdom also became Catholic centers. Butrint in the south, Vlorë, and Krujë also became Catholic once the kingdom was formed.

Many new Catholic churches and monasteries were built. Different religious groups, like the Dominicans and Franciscans, came to the country. Papal missionaries also arrived. Many Albanians who were not Catholic converted, and many Albanian priests and monks went to Catholic schools in Dalmatia.

However, in Durrës, the Byzantine (Orthodox) way of worship continued for a while. This mix of religions sometimes confused people. One visitor described Albanians as "neither entirely Catholic nor entirely schismatic." To fix this, in 1304, Pope Benedict XI ordered Dominicans to teach locals the Latin (Catholic) way. Dominican priests were also appointed as bishops in Vlorë and Butrint.

Krujë became a key center for Catholicism. Its bishopric had been Catholic since 1167 and was directly under the Pope. Local Albanian nobles had good relations with the Pope, and their influence grew so much that they started nominating local bishops.

The spread of Catholicism faced challenges when Stefan Dušan ruled Albania. The Catholic faith was called "Latin heresy," and Dušan's laws had strict rules against Catholics. However, persecutions of local Catholic Albanians began even before 1349. This made the relationship between local Catholic Albanians and the Pope very close.

Between 1350 and 1370, Catholicism in Albania reached its peak. There were about seventeen Catholic bishoprics, which helped spread Catholic reforms and missionary work in nearby areas.

Society and Daily Life

The Angevins brought a Western style of feudalism to Albania. Before, the Byzantine Pronoia system was common. In the 13th and 14th centuries, landholders (pronoiars) gained many special rights. They took power from the central government. They started collecting land taxes themselves and even acted as judges for minor and then serious crimes.

By the 14th century, land ownership became like feudal property. It could be passed down, divided, and sold. These lands were less and less used to provide soldiers for the state. Besides pronoiars, there were other landowners who had large areas worked by farmers. Citizens of Durrës, Shkodër, and Drisht also owned land.

Feudal lands in Albania, like in the West, had two parts: land for peasants and land directly owned by the lords. The peasants' land was spread out in small plots. The lords' land grew as the nobles became more powerful.

Religious groups like monasteries and bishoprics also owned a lot of land. In the 14th century, they had collected large amounts of land. Their income came mainly from farming, but also from crafts. They also collected taxes in goods and money. Sending money to Rome or Constantinople sometimes caused problems between local clergy and the Pope or Patriarch.

To get more money, especially during wars, the government put high taxes on people. Most people in society were farmers. Some were "free" farmers, others were "foreign" farmers who had no land and worked for wages. Eventually, they received small plots of land and paid duties, becoming like other farmers.

The duties of peasants varied by region. Payments in goods or cash also changed. As nobles gained more power in the 13th century, cash payments increased. Feudal control spread from plains to mountainous areas. Common lands like forests and pastures also came under noble control. This happened as the Byzantine Empire declined, turning the pronoia system into something very similar to Western feudalism.

Most people living under lords were farm workers. Records show that in many parts of Albania, villagers became serfs (tied to the land). A traveler in 1308 noted that farmers in areas like Këlcyrë and Tomorricë worked their lords' lands and vineyards, gave them products, and did household chores. The historian Kantakouzenos said that the power of these lords mainly came from their large numbers of livestock.

Cities and Urban Life

In the 13th century, many Albanian cities changed from being just military forts to busy urban centers. They grew beyond their walls, forming new neighborhoods called proastion or suburbium. These areas became important for trade, with shops and workshops. Eventually, these new parts were also walled for protection. To get water, people used cisterns (tanks) to collect rainwater. Sometimes, water came from nearby rivers.

By the early 14th century, city populations grew a lot. Durrës, for example, is thought to have had 25,000 people. Cities attracted people from rural areas, including farmers who often had to pay a fee or work for the city. Nobles from surrounding areas also moved to cities, either permanently or to manage their businesses. Many owned property, stores, and houses in the city. Nobles becoming city citizens and taking government jobs became common.

Architecture and Buildings

The spread of Catholicism influenced the style of religious buildings. A new Gothic style appeared, mainly in Central and North Albania. These areas had stronger ties to the Catholic Church and Western Europe. In Durrës and nearby areas, both Catholic and Orthodox churches operated, so both Western and Byzantine building styles were used. Western architecture was also found in areas controlled by Western rulers.

Churches built in this period in Upper and Central Albania often had a long East-West layout with round or rectangular apses (curved ends). Important buildings from this time include the Church of Shirgj Monastery near Shkodër, the Church of Saint Mary in Vau i Dejës (both 13th century), and the Church of Rubik (12th century). Most churches from this period were decorated with murals (wall paintings).

Rulers of the Kingdom

Kings of Albania

- Charles I (1272–1285)

- Charles II (1285–1294)

Charles II gave his rights to Albania to his son Philip in 1294. Philip then ruled as Lord of the Kingdom of Albania.

Lords of the Kingdom of Albania

- Philip (1294–1331)

- Robert (1331–1332)

Philip died in 1331, and his son Robert took over. Robert's uncle, John, did not want to be loyal to Robert for his lands. So, Robert gave John the rights to the smaller Kingdom of Albania in exchange for money and other lands. John then took the title of Duke of Durazzo.

Dukes of Durazzo

- John (1332–1336)

- Charles (1336–1348)

- Joanna (1348–1368)

- Louis (1366–1368 and 1376), ruling with his wife

In 1368, Durazzo was captured by Karl Topia, who was recognized by Venice as Prince of Albania.

Captains and Vicars-General of the Kingdom of Albania

- Gazo Chinard (1272)

- Anselme de Chaus (May 1273)

- Narjot de Toucy (1274)

- Guillaume Bernard (September 23, 1275)

- Jean Vaubecourt (September 15, 1277)

- Jean Scotto (May 1279)

- Hugues de Sully le Rousseau (1281)

- Guillaume Bernard (1283)

- Guy of Charpigny (1294)

- Ponzard de Tournay (1294)

- Simon de Mercey (1296)

- Guillaume de Grosseteste (1298)

- Geoffroy de Port (1299)

- Rinieri da Montefuscolo (1301)

Marshals of the Kingdom of Albania

- Guillaume Bernard

- Philip d'Artulla (Ervilla)

- Geoffroy de Polisy

- Jacques de Campagnol

- Andrea I Muzaka (1279)

- Gulielm Blinishti (1304)

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Albania (medieval) para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Albania (medieval) para niños