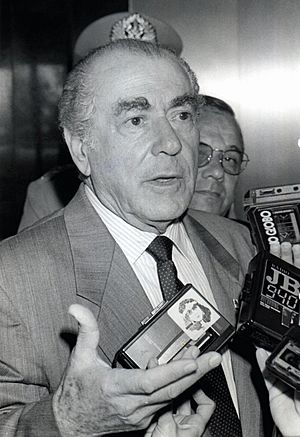

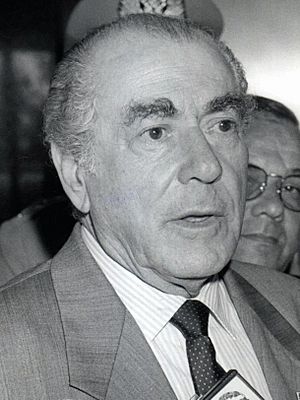

Leonel Brizola facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Leonel Brizola

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Governor of Rio de Janeiro | |

| In office 15 March 1991 – 1 April 1994 |

|

| Vice Governor | Nilo Batista |

| Preceded by | Moreira Franco |

| Succeeded by | Nilo Batista |

| In office 15 March 1983 – 15 March 1987 |

|

| Vice Governor | Darcy Ribeiro |

| Preceded by | Chagas Freiras |

| Succeeded by | Moreira Franco |

| Federal Deputy for Guanabara | |

| In office 14 May 1963 – 9 April 1964 |

|

| Governor of Rio Grande do Sul | |

| In office 29 March 1959 – 25 March 1963 |

|

| Preceded by | Ildo Meneghetti |

| Succeeded by | Ildo Meneghetti |

| 26th Mayor of Porto Alegre | |

| In office 1 January 1956 – 29 December 1958 |

|

| Vice Mayor | Tristão Sucupira Viana |

| Preceded by | Martim Aranha |

| Succeeded by | Tristão Sucupira Viana |

| Federal Deputy for Rio Grande do Sul | |

| In office 1 February 1955 – 1 January 1956 |

|

| State Deputy of Rio Grande do Sul | |

| In office 10 March 1947 – 31 January 1955 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Leonel de Moura Brizola

22 January 1922 Carazinho, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil |

| Died | 21 June 2004 (aged 82) Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Political party | PDT (1979–2004) Independent (1964–1979) PTB (1945–1964) |

| Spouse |

Neusa Goulart

(m. 1953; died 1993) |

| Relations | João Goulart (brother-in-law) |

| Children | 3 (José Vicente, João Otávio and Neusinha) |

| Alma mater | Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul |

| Profession | Civil engineer |

Leonel de Moura Brizola (born January 22, 1922 – died June 21, 2004) was an important Brazilian politician. He was the only person to be elected governor of two different Brazilian states. These states were Rio Grande do Sul and Rio de Janeiro.

Brizola started his political journey with the help of former Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas. He was trained as an engineer. He helped create the youth group of the Brazilian Labour Party. He also served as a state representative and mayor of Porto Alegre.

In 1958, he became governor of Rio Grande do Sul. He played a big role in stopping a military attempt to take over the government in 1961. This attempt tried to prevent João Goulart from becoming president. Later, in 1964, when a military dictatorship began in Brazil, Brizola wanted to fight back. However, Goulart did not want a civil war, so Brizola went into exile in Uruguay.

After the dictatorship ended in 1979, Brizola returned to Brazil. He founded a new political party called the Democratic Labour Party (PDT). This party focused on ideas like democratic socialism and nationalism. He called his unique approach socialismo moreno ("tanned socialism"). In the 1980s, he was elected governor of Rio de Janeiro twice. He also ran for president in 1989 but came in third place. Brizola is remembered as a very important figure in Brazil's left-wing politics.

Contents

Early Life and Political Start (1922–1964)

Leonel Brizola's father, José Brizola, was a small farmer. He died fighting in a local civil war in 1923. Leonel was originally named Itagiba. But he later chose the name Leonel, inspired by a rebel leader.

Brizola left home at age eleven. He worked many odd jobs, like delivering newspapers and shining shoes. With help from a Methodist minister's family, he got a scholarship. This allowed him to finish high school and go to college in Porto Alegre. He earned a degree in engineering. However, he never worked as an engineer.

Instead, he entered politics in his early twenties. He joined the youth group of the Brazilian Labor Party (PTB) in 1945. In 1946, while still a student, he was elected to the Rio Grande State Legislature. The Labor Party was created to support former President Getúlio Vargas. Brizola became friends with Vargas's family, which helped him meet Vargas himself.

In 1950, Brizola married Neusa Goulart, who was João Goulart's sister. Vargas was their best man at the wedding. This marriage helped Brizola become a wealthy landowner and a regional leader in his party.

Brizola quickly took on many roles. He served two terms in the Rio Grande State Legislature. He was also State Secretary for Public Works and a federal congressman. From 1956 to 1958, he was the Mayor of Porto Alegre. In 1958, he resigned to run for State Governor. During Goulart's presidency (1961-1964), Brizola became a key national supporter of his brother-in-law.

As governor of Rio Grande do Sul (1959–1963), Brizola became known for his social policies. He quickly built many public schools in poor areas, which were nicknamed brizoletas. He also supported policies to help small farmers and landless rural workers. He helped create an organization called MASTER for these workers.

Brizola gained national attention in 1961. When President Jânio Quadros resigned, military leaders tried to stop Vice-President Goulart from becoming president. They claimed Goulart had ties to communism. Brizola got support from a local army commander. He used radio stations in Rio Grande do Sul to create a "legality broadcast." This broadcast called on citizens to protest against the military's actions.

Brizola even prepared to give firearms to civilians if needed. After twelve days of tension, the coup attempt failed. Goulart was then able to become president.

Nationalizing Public Services

Brizola also became known internationally for his nationalist policies. As governor, he wanted to quickly industrialize his state. This led him to take control of American-owned public service companies in Rio Grande. These included ITT and Electric Bond & Share.

Brizola explained that these foreign companies were not investing enough. They were also charging high prices for services. He believed they were not helping the state's long-term industrialization plans. He offered ITT a chance to join a new company, but they refused.

Many people, including some American scholars, later agreed with Brizola's reasons. They noted that even the military government that exiled Brizola later had to nationalize Brazil's telecommunications system. This was done to develop necessary infrastructure.

Brizola's actions caused diplomatic problems with the United States. The U.S. government was trying to help Brazil financially. Brizola's nationalizations were seen as a challenge. President Goulart eventually agreed to pay compensation to the American companies. Brizola saw this as Goulart giving in to foreign pressure.

Brizola became a major figure in Brazilian politics. He even hoped to become president himself. However, Brazilian law at the time did not allow close relatives of the president to run for the next term. Between 1961 and 1964, Brizola pushed for major social and political changes. He was seen as a strong and direct leader. In 1962, he won a huge election to become a representative for the state of Guanabara (Rio de Janeiro).

Strong Leadership and Disagreements with Goulart

In 1963, a public vote restored Goulart's full power as head of government. Around this time, Brizola started his own weekly radio show. He used it to share his ideas across the country. He also planned to create small groups of armed men, called "elevensome" Grupos de Onze. These groups were meant to support his reform ideas. Brizola was very good at using strong, clear language in his speeches.

Some people saw Brizola as too extreme. They believed his strong ideas made it hard for the government to find solutions. For example, the U.S. ambassador to Brazil, Lincoln Gordon, compared Brizola's methods to those of Joseph Goebbels. Many American media and thinkers also disliked Brizola.

In late 1963, Brizola tried to become the Minister of Finance. He wanted to use this position to push his radical plans. He said, "if we want to make a revolution, we must have the key to the safe." But he did not get the job. This made the political situation in Brazil even more tense.

A disagreement grew between Brizola and Goulart. Brizola believed Goulart might try to stop the political changes. He thought the only way to prevent this was a revolution led by the people. Many historians believe Brizola's strong views made it harder for Goulart's government to find common ground. Some say Brizola was too focused on his own goals. Others argue that Brizola was simply pushing for important changes that the powerful classes did not want.

Exile and Return (1964–1979)

In April 1964, a coup d'état (a sudden takeover of government) removed Goulart from power. Brizola was the only major political leader to support Goulart. He tried to gather army units in Porto Alegre to fight back. Brizola gave a passionate speech, urging soldiers to "occupy barracks and arrest the generals." This made him a lasting enemy of the new military government.

After a month of trying to resist, Brizola fled to Uruguay in May 1964. Goulart was already there in exile. Brizola spent most of the next ten years alone in Uruguay. He managed his wife's property and kept up with news from Brazil. He refused to join other opposition groups that wanted to pressure the military government. He also broke ties with his brother-in-law, João Goulart, during this time.

Rescue from Uruguay and Exile in the U.S. and Europe

Brazilian intelligence closely watched Brizola during his exile. In the late 1970s, a military government also took power in Uruguay. This allowed the Brazilian and Uruguayan militaries to work together to capture Brizola. This was part of a secret plan called Operation Condor, where Latin American dictatorships cooperated to hunt down opponents.

However, U.S. policy towards Latin America had changed. The Jimmy Carter administration was trying to stop human rights abuses. This intervention helped save Brizola. He was very grateful to Carter for this help. This event also changed Brizola's political views, which surprised some of his leftist friends.

Between 1976 and 1977, several prominent Brazilian political figures died under mysterious circumstances. This made Brizola feel unsafe in Uruguay. He sought help from the American Embassy in Uruguay. Despite some opposition, he was given a special visa. In mid-1977, Brizola was deported from Uruguay. He then traveled to the United States and was granted asylum there.

Brizola's rescue is seen as a success for Carter's human rights efforts. After arriving in New York, Brizola met with U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy. Kennedy helped him get permission to stay in the U.S. for six months. From his hotel, Brizola connected with other Brazilian exiles and American academics who wanted to end military rule in Brazil.

Later, Brizola moved to Portugal. There, he joined the Socialist International group. He supported a plan for a democratic Brazil after the dictatorship. While in the U.S., Brizola also met an Afro-Brazilian activist. This meeting influenced his later political ideas about identity groups. In a political statement from Lisbon, he said that Black and Native Brazilians faced more severe exploitation. He believed they needed special help. He also sought to help people from Northeastern Brazil, marginalized children, and women. This showed his party wanted to appeal to many different groups.

In the late 1970s, the Brazilian military dictatorship was weakening. In 1978, many exiles were quietly given passports to return. But Brizola was still blacklisted as a "public enemy number one." Finally, in 1979, a general amnesty was declared. This allowed Brizola to end his exile and return to Brazil.

Later Political Career (1979–2004)

When Brizola returned to Brazil, he wanted to bring back the Brazilian Labour Party. But new movements had emerged, like the metalworkers' unions led by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Brizola was not allowed to use the old party name. Instead, he founded a new party, the Democratic Labour Party (PDT). In 1986, the PDT joined the Socialist International. Its symbol became the fist and rose.

Brizola quickly regained his political influence in Rio Grande do Sul. He also became very strong in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Instead of focusing on organized labor, he sought support from the urban poor. He connected traditional nationalism with a style of populism that appealed to the less organized. For his supporters, Brizola aimed to empower the poorest working classes. He adopted a Christian message of friendship to all people.

In 1982, Brizola ran for governor of Rio de Janeiro. This was the first direct election for governor in that state since 1965. He chose candidates for Congress who were not traditional politicians. These included a Native Brazilian leader and an Afro-Brazilian activist. Brizola called his ideology Socialismo Moreno ("Socialism of Color" or "mixed-race socialism"). He focused his campaign on education and public safety.

To ensure his victory in 1982, Brizola publicly spoke out against what he believed was an attempt to rig the vote. A company hired to count ballots was giving out slow results from areas where Brizola was losing. Brizola exposed this alleged fraud in press conferences and on live television. His actions prevented the scheme from succeeding, and he was officially declared the winner.

As governor of Rio (1983–1987), Brizola continued to be a visible political figure. He launched a big education program. This involved building large high schools called CIEPs ("Integrated Centers for Public Education"). These schools, designed by Oscar Niemeyer, were meant to be open all day. They would provide food and activities for students. Brizola also worked to provide public services and legal housing for people living in shanty towns (favelas). He believed that favelas were part of the solution, not the problem. He thought that if people had property rights and basic services, they could improve their own homes.

Brizola also changed police policy in the favelas. He ordered the state police to stop random raids. He also cracked down on vigilante groups that included police officers. Some people criticized these policies, saying they allowed organized crime to grow. Others argued that the military dictatorship had made crime worse by putting criminals and political prisoners together.

Brizola's policies were sometimes criticized for being disorganized and spending too much public money. However, they also helped him gain the support needed to run for president in 1989.

In the 1989 presidential election, Brizola's strong leadership faced challenges. He finished third in the first round, narrowly losing the second spot to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Lula's Workers' Party had more organized activists and support from social movements. Fernando Collor de Mello eventually won the election. Brizola won big in his home states of Rio Grande do Sul and Rio de Janeiro. But he received very few votes in São Paulo. Lula, however, gained many new voters in the Northeast. Lula beat Brizola by a very small margin to go to the runoff election.

Brizola strongly supported Lula in the 1989 runoff election. He famously said that politics is "the art of swallowing toads." He meant that forcing the Brazilian elite to accept Lula as president would be like making them "swallow the Bearded Toad," referring to Lula. Brizola's support was very important in helping Lula gain votes in Rio de Janeiro and Rio Grande do Sul.

Later Years and Passing (1989–2004)

After the 1989 election, Brizola still hoped to become president. Some of his advisors suggested he run for the Senate to gain national attention. But Brizola chose to run for governor of Rio de Janeiro again in 1990. He won a second term with a large majority.

Brizola's second term as governor was difficult. It was marked by disorganized management and his tendency to centralize power. He also supported the Collor government, which later faced impeachment.

Without strong national support and abandoned by some close allies, Brizola ran for president again in 1994. This was during the success of Fernando Henrique Cardoso's economic plan. Brizola's campaign was not successful, and he finished in fifth place. Cardoso was elected president in the first round. This marked the end of Brizola's political movement as a major national force.

During Cardoso's first term, Brizola criticized his policies of privatizing public companies. In 1995, he warned that if there was no civilian reaction to privatization, there would be a military one. Four years later, when Cardoso ran for re-election, Brizola ran as Lula's vice-presidential candidate. They both lost to Cardoso.

In his final years, Brizola's relationship with Lula and the Workers' Party changed. He did not support Lula in the first round of the 2002 presidential election. Instead, he supported Ciro Gomes and ran for a Senate seat. Gomes finished third, and Brizola lost his Senate bid. Lula was elected president. Brizola supported Lula in the second round of the 2002 election.

In his last public appearances, Brizola criticized Lula. He felt Lula was adopting policies that were not aligned with traditional left-wing values.

Leonel Brizola passed away on June 21, 2004, from a heart attack. He had been planning to run for president in 2006.

On December 29, 2015, a law was approved by President Dilma Rousseff. This law added Brizola's name to the Book of Heroes of the Motherland. This book officially recognizes Brazilians who have shown exceptional commitment and heroism for their country.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Leonel Brizola para niños

In Spanish: Leonel Brizola para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |