Getúlio Vargas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Getúlio Vargas

|

|

|---|---|

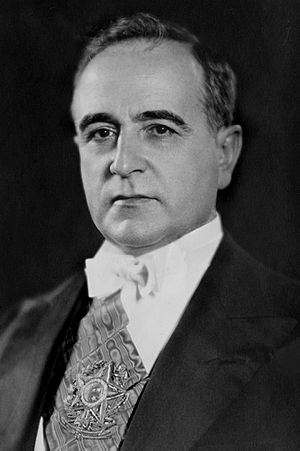

Official portrait, 1930

|

|

| President of Brazil | |

| In office 31 January 1951 – 24 August 1954 |

|

| Vice President | Café Filho |

| Preceded by | Eurico Dutra |

| Succeeded by | Café Filho |

| In office 3 November 1930 – 29 October 1945 |

|

| Vice President | None |

| Preceded by | Military Junta (interim) |

| Succeeded by | José Linhares (interim) |

| Senator for Rio Grande do Sul | |

| In office 5 February 1946 – 31 January 1951 |

|

| Preceded by | Simões Lopes |

| Succeeded by | Camilo Mércio |

| President of Rio Grande do Sul | |

| In office 25 January 1928 – 9 October 1930 |

|

| Vice President | João Neves |

| Preceded by | Borges de Medeiros |

| Succeeded by | Osvaldo Aranha |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 15 November 1926 – 17 December 1927 |

|

| President | Washington Luís |

| Preceded by | Aníbal Freire |

| Succeeded by | Oliveira Botelho |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 26 May 1923 – 6 November 1926 |

|

| Constituency | Rio Grande do Sul |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of Rio Grande do Sul | |

| In office 20 September 1917 – 26 May 1923 |

|

| Constituency | At-large |

| In office 20 September 1909 – 6 October 1913 |

|

| Constituency | At-large |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas

19 April 1882 Santos Reis Farm, São Borja, Rio Grande do Sul, Empire of Brazil |

| Died | 24 August 1954 (aged 72) Catete Palace, Rio de Janeiro, Federal District, Brazil |

| Resting place | XV de Novembro Square, São Borja, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil |

| Political party | PTB (1946–1954) |

| Other political affiliations |

PRR (1909–1930) Independent (1930–1946) |

| Spouse |

Darci Sarmanho

(m. 1911) |

| Children | 5, including Lutero and Alzira |

| Parents | Manuel do Nascimento Vargas Cândida Francisca Dornelles |

| Alma mater | Free Faculty of Law of Porto Alegre |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1898–1903 1923 |

| Rank | Sergeant Lieutenant Colonel |

| Unit | 6th Infantry Battalion 25th Infantry Battalion 7th Provisional Division |

| Battles/wars | Acre War 1923 Revolution |

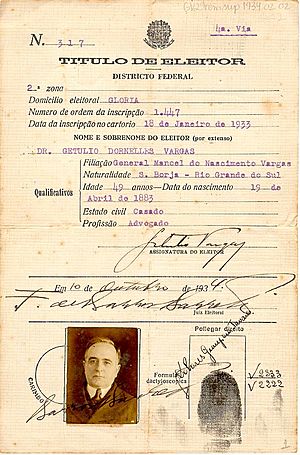

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas (born April 19, 1882 – died August 24, 1954) was a Brazilian lawyer and politician. He served as the 14th and 17th president of Brazil. His first time as president was from 1930 to 1945. His second time was from 1951 to 1954. Many historians believe he was the most important Brazilian politician of the 20th century. This is because he was in power for a long time and made many changes.

Vargas was born in São Borja, Rio Grande do Sul. His family was powerful in the area. He was in the Army for a short time before studying law. He started his political career as a district attorney. Then he became a state deputy. After a break, he returned to the state Legislative Assembly. Vargas even led troops during a civil war in Rio Grande do Sul in 1923.

He entered national politics as a member of the Chamber of Deputies. Later, he became Minister of Finance under President Washington Luís. He then became the state president (governor) of Rio Grande do Sul. During this time, he was very active and introduced many new policies.

In 1930, Vargas lost the presidential election. But he came to power after an armed revolution. He became a provisional president. In 1934, he was elected president under a new constitution. Three years later, he took more power. He claimed there was a risk of a communist uprising. This started the eight-year Estado Novo dictatorship. In 1942, he led Brazil into World War II on the side of the Allies. This happened because Brazil was caught between Nazi Germany and the United States.

There was opposition to his government. Major revolts happened, like the 1932 Constitutionalist Revolution. Also, there was the Communist uprising of 1935 and the Integralist Uprising. But Vargas stopped all of them. He used different ways to deal with his opponents, from peaceful talks to putting them in jail. Vargas was removed from power in 1945 after fifteen years. But he returned to the presidency in 1950 after winning a democratic election. His second time as president ended when he died in 1954.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Family Background and Childhood

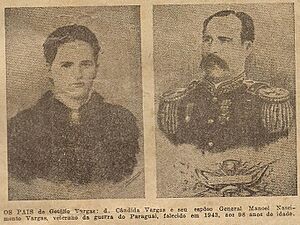

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas was born on April 19, 1882. He was born in São Borja, Rio Grande do Sul. He was the third of five sons. His parents were Manuel do Nascimento Vargas and Cândida Dornelles Vargas. São Borja was a town near Brazil's border with Argentina. It was known for smuggling and conflicts. The Vargas family was part of this history. In 1919, people complained about the Vargases' "forceful" actions.

Vargas's mother, Cândida, was described as "short and pleasant." Her family came from the Azores. They helped found Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul. Vargas's father, Manuel, was a respected military general. He fought in the Paraguayan War. He was also a local leader for the Rio-grandense Republican Party. His family also had roots in the Azores and São Paulo. During the Federalist Revolution, his parents' families were on opposite sides. Their marriage brought these two groups together.

Vargas had a happy childhood. His mother was respected in town because she was connected to both political sides. Vargas went to a private school in São Borja. But he did not finish there. He was sent to a school in Minas Gerais. Vargas traveled by boat from Buenos Aires. He hurried overland because of a yellow fever outbreak in Rio de Janeiro. At school, other students made fun of him. They called him xuxu (chayote) because he was short and round. Vargas and his older brothers had to leave the school. This happened after his brother Viriato shot another student.

Military Career and Law School

Like his father, Vargas joined the military. He joined the Army in 1898. He was a private in the 6th Infantry Battalion. In 1899, he was promoted to sergeant. He also studied at a military college until 1901. Vargas and other students had to leave the college after protesting about a lack of water. They were later allowed to return.

Vargas was then transferred to Porto Alegre. He joined the 25th Infantry Battalion. He wanted to leave the Army to study law. But his discharge was delayed. He was sent to Corumbá because of a border problem between Bolivia and Brazil in 1903. Vargas did not have to fight. The problem was solved before he arrived. He later said that living in tough conditions taught him to understand others. He asked for a discharge again. He was able to get papers that falsely said he had epilepsy.

Vargas was accepted into law school in Porto Alegre. He fit in easily with the other students. He became active in the students' republican group. He also worked as an editor for the school newspaper. Vargas and his friends were inspired by a politician named Júlio Prates de Castilhos. They created a group to keep his ideas alive. Vargas was the top student in his class. He lived in boarding houses where he met future president Eurico Gaspar Dutra. Vargas spoke to President Afonso Pena in 1906. He said that education was key for a democratic government. Vargas graduated in 1907.

Early Political Career

Attorney and State Deputy

After law school, Vargas joined the Rio-grandense Republican Party. He could either teach at his law school or become a state attorney. Vargas chose to be a state attorney. His father helped him get this job. He was named the Rio Grande do Sul state attorney general. Vargas stayed in this role until 1908.

As state attorney, Vargas gained important experience. He became known for being loyal and smart. In 1909, he was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Rio Grande do Sul. He was only in his twenties, but he became known for his ability to handle difficult situations. He was well-liked. The Legislative Assembly met for only two months a year. The pay was low, so Vargas needed other ways to earn money. He started a legal career as a public prosecutor in Porto Alegre.

Personal Life and Political Break

Vargas did not stay a prosecutor for long. In March 1911, he married fifteen-year-old Darci Lima Sarmanho. She was thirteen years younger than him. They were married for 47 years until Vargas died in 1954. Darci was the daughter of Antonio Sarmanho, a friend of Vargas's father. She became an orphan at fourteen. Darci mostly stayed out of the public eye. She managed their homes and later worked on public charity projects when Vargas became president.

They had five children: Lutero, Jandira, Alzira, Manuel, and Getúlio. Alzira later became a lawyer and was Vargas's favorite child. Vargas's father gave him land and money to start a home and law practice in São Borja. Having both a political and legal job was common in Latin America. Vargas became a problem-solver and advisor. He took on many cases that dealt with social issues. This experience helped him later with his social reforms.

From 1913 to 1917, Vargas took a break from politics. He had a disagreement with the state president, Borges de Medeiros. Vargas left the Assembly. Historian Richard Bourne said Vargas left in a smart way. He made it clear he should be taken seriously, but did not cause a big fight. This made it possible for him to return later.

Political Rise

Return as a Legislator and the 1923 Civil War

Medeiros still needed the support of the powerful Vargas family. In late 1916, Medeiros offered Vargas the job of state police chief. Vargas turned it down. Instead, he successfully ran for reelection as a state deputy. He served two terms. During this time, he was called the "mathematician of the party." He became the party leader. Vargas was responsible for making sure Medeiros was reelected. He also led a group that checked election results. His opponents said he was involved in electoral fraud. Later in his term, Vargas was in charge of the state budget.

During the 1923 civil war in Rio Grande do Sul, Vargas was asked to lead a military unit. He organized the Seventh Provisional Division. When other Republican leaders were under attack, Vargas led 250 soldiers. He marched 100 miles at night to Uruguaiana. He wanted to "defend the ideas of his party." Halfway there, he found the railway cut. There were no horses for his soldiers. Vargas was determined and quick. He ordered his troops to leave the town. He made them get on river barges. Vargas ignored warnings about low water levels to help the Republicans. He said he would do everything possible to help his comrades.

Before he could lead any real fighting, President Medeiros sent Vargas a message. Vargas had been named a federal deputy. Deputies could only command troops with permission from the National Congress. Vargas gave his command to his cousin. He immediately left for Rio de Janeiro. He now had a more important job: to bring back the power of Rio Grande do Sul in national politics.

National Politics

In May 1923, Vargas became a national deputy. He was Medeiros's trusted man during a difficult time. His goal was to reduce federal involvement in the state civil war. He gave a speech saying the state government had the situation under control. In truth, this was not entirely true. Medeiros had to get private loans from Uruguay to pay for war costs. Vargas also had to lead his group of deputies from Rio Grande do Sul. They were discouraged after a newspaper called for accepting the new president, Arthur Bernardes. In 1924, Vargas became the official leader of the Rio Grande do Sul group in Congress. That same year, he had to take his daughter Alzira out of school. This happened after a warship fired on Rio de Janeiro as part of the tenente rebellions.

According to historian Levine, Vargas's biggest achievement as a congressman came in 1925. He was part of a group studying changes to the constitution. He argued for more government power. Vargas knew that a politician from São Paulo would follow Bernardes as president. So, Vargas built relationships with the São Paulo group during Bernardes's presidency. When Washington Luís was elected president in 1926, he chose Vargas to be his Minister of Finance. Vargas had almost no experience with money matters. He had even refused to join a finance committee in Congress. This appointment was a thank you to Medeiros for helping Luís become president. It was also part of a political deal to divide cabinet jobs among important states.

The economy was good from 1926 to 1928. But it depended only on coffee. Within a month, Vargas presented a money reform bill to Congress. It aimed to make the Brazilian currency stable. It worked at first, but then failed after the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Vargas introduced a tax on consumption. This was to make the country less dependent on taxes from imports. He also held meetings where up to a hundred people could present their requests and complaints. These people ranged from regular citizens to congressmen. Vargas only served two years as Finance Minister. He returned to Rio Grande do Sul to become its president (governor) in 1928. But he gained important recognition and experience at the national level.

President of Rio Grande do Sul

In 1928, Medeiros was finishing his long time as president of Rio Grande do Sul. Vargas was careful. He even stopped a journalist from writing about his public meetings. He thought it would look like he was trying to become president. Medeiros had a lot of control over who would follow him. He could have stopped any choice. But Vargas had many things in his favor. These included Medeiros's debt, Vargas's national achievements, his distance from state arguments, and his popularity among young party members. He was also good at solving difficult situations.

Medeiros chose Vargas as his successor. Vargas then resigned from Luís's cabinet in late 1927. There was no strong opposition. The Republican political machine made sure Vargas would win. He became the president of the state. His term was set to end in 1932.

Vargas was very active during his two years in office. Once, he stopped dishonest election results that favored his own party. In another case, he helped create a ceasefire between two fighting groups in his state. He successfully ended decades of conflict. He also made peace with other groups in the state. He gave some things to the Liberationists. Levine said, "As governor, Vargas achieved bipartisan support for his government, for the first time in generations."

With Osvaldo Aranha, who managed his economic plans, Vargas gave money to cattle ranchers. He created groups to bring in resources and lower export prices for farm products. Vargas started the Banco do Rio Grande do Sul (Bank of Rio Grande do Sul). This bank lent money to farmers. He also worked on education, mining, farming, and roads. People supported him as he encouraged planting wheat and created a department of agriculture. Vargas doubled the number of primary schools in the state. He oversaw the building of bridges and roads. He also changed the railroad contract between Rio Grande do Sul and the federal government to benefit the state. Despite this, he remained loyal to Luís's government. He kept his connections to the federal government. Vargas also supported the VARIG airline and improved law courts.

Becoming President

Presidential Nomination and Campaign

During most of the First Brazilian Republic (1889–1930), Brazilian politics were controlled by an alliance. This was known as coffee with milk politics. It joined politicians from the powerful states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais. Starting in the 1910s, many people were unhappy with the Republic. There was a general strike in 1917. Several military revolts by unhappy junior officers also failed in the 1920s.

In October 1929, world coffee prices crashed. This also crashed the Brazilian economy. Amid unrest and economic collapse, President Luís broke the coffee and milk agreement. He chose Júlio Prestes from São Paulo as his successor. This went against the four-decade-old agreement. Vargas spoke about his views on the Old Republic on October 4, 1930:

The people are starving and oppressed. The government has been destroyed by powerful groups and politicians. Cruelty, violence, and wasting public money are seen everywhere in Brazilian politics.…

President Luís choosing a São Paulo politician led to a political crisis. The Liberal Alliance was formed. It included Minas Gerais, Rio Grande do Sul, and Paraíba. This group opposed Prestes. They nominated Vargas for president. Vargas led a wide group of middle-class business owners, farmers from outside São Paulo, and the tenentes. Support for Vargas was very strong in the states of the alliance. During the campaign, Vargas was careful not to upset landowners. But he did support some social reforms and economic nationalism. The Liberal Alliance also pushed for agricultural schools, industrial training, and better health in the countryside. They wanted workers' vacations, a minimum wage, and political reforms. Vargas would later put many of these ideas into action.

The Revolution of 1930

Julio Prestes was declared the winner of the 1930 election. Many people claimed there was electoral fraud. Both sides had cheated. Voting machines produced votes in all Brazilian states, including Rio Grande do Sul. Vargas won 298,627 votes there, but Prestes won overall with 982,000. Many in the opposition thought about planning a coup. But Vargas said they did not have enough power to challenge the election. It seemed the coup would not happen.

However, Vargas's running mate, João Pessoa, was killed for personal reasons. After this, the opposition decided it was time to fight. Vargas agreed. The president was elected in March but was not to take office until November. This gave Luís time to hand over power to Prestes. Vargas and his co-conspirators planned to overthrow the government. This revolution, known as the Revolution of 1930, began on October 3.

Railway workers went on strike. The capital of Pernambuco, Recife, was taken over by its citizens. They invaded government buildings and a telephone station. Revolutionaries quickly took control of the Northeast. A big military fight was expected in São Paulo. But it never happened. Luís resigned on October 24, 1930. The military and a cardinal urged him to do so. This cleared the way for a short-lived military group to take charge. This group was made up of Brazil's military leaders.

The revolutionary leaders were surprised that the President was removed without their knowledge. Vargas traveled by train to São Paulo. He continued toward Rio de Janeiro, which was the capital at the time. He sent a message to the military group on October 24, 1930:

I am on the São Paulo border with thirty thousand men perfectly armed and acting in combination with the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Paraná, Santa Catarina, Minas Gerais and the north, not to depose Washington Luis, but to realise the program of the revolution… I am merely a transitory expression of the collective will. Members of the junta of Rio de Janeiro will be accepted as collaborators but not directors, since these elements joined the revolution at the time when its success was assured. Under these conditions, I will enter with the southern forces into the state of São Paulo, which will be occupied by troops I can trust. We will arrange the trip to Rio [de Janeiro] later. It is unnecessary for me to say that the march upon São Paulo and the subsequent military occupation is merely to guarantee military order. We have no desire to antagonise or humiliate our brothers from this state, who deserve only our esteem and appreciation. Before beginning our march for São Paulo tomorrow I want to hear any proposals that the junta may wish to make.

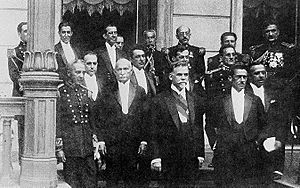

Vargas arrived in Rio de Janeiro in a uniform and a wide hat. There were 3,000 soldiers in the city ready for his arrival. The military group stepped down. They made Vargas "interim president" on November 3, 1930.

Provisional Government (1930-1934)

Taking Power

Vargas's provisional presidency started on November 3, 1930. He took "unlimited power" after the 1930 Revolution. He gave a speech outlining his 17-point plan. He put his main political opponents in jail. Instead of following the old constitution, Vargas chose a "revolutionary solution." He took emergency powers with a provisional government. He had told Aranha about this plan earlier. Even the poorest Brazilians had hope in Vargas. This pushed him to achieve his goals. For a while, Brazilians lived under a government that had no political parties and ruled by decree. They accepted this. Vargas also liked the idea of a corporatist state.

The old political formula, stressing the rights of man, appears to be decadent. Instead of individualism, synonym for an excess of liberty, and of communism, a new mentality for slavery, the perfect co-ordination of all initiatives should prevail, circumscribed within the orbit of the State; and class organisations should be recognised as collaborators in public administration.

Through his provisional government, Vargas clearly tried to centralize his power. He dissolved state and city legislatures, as well as the National Congress. Vargas took all power to make laws and decisions. He could also appoint and remove public officials as he wished. However, the court system was allowed to stay, with some changes. To ensure support, Vargas appointed federal "interventors" to run the Brazilian states. These interventors replaced the state presidents (governors). The only exception was Minas Gerais, where the president was allowed to stay. Almost all these actions were put into one decree on November 11, 1930.

Coffee Policy

Since the start of the Great Depression, there was no demand for Brazil's farm products. Farmers faced financial ruin. Unemployment in cities grew. Money from other countries decreased. And paper money that could be exchanged for gold was no longer used. For example, coffee prices were 22.5 cents per pound in 1929. But this dropped to only eight cents in 1931. Vargas encouraged growing different crops, especially cotton. But he also knew he could not abandon the coffee industry. Brazil depended heavily on it.

So, Vargas's government took steps to help the coffee industry. On February 10, 1933, Vargas created the National Coffee Department (DNC). In March 1931, Vargas issued a decree. It stopped imports of machinery for industries that were producing too much. Still, Vargas's government faced a big problem. Large amounts of coffee had no buyers in the world market. In July 1931, the government used money from export taxes to buy extra coffee. They then destroyed some of it. This helped keep coffee prices up and reduced the supply. This plan lasted many years, ending only in 1944. By then, Vargas's government had destroyed 78.2 million sacks of coffee. This was equal to the world's coffee use for three years.

Labor Policy

Historians Boris and Sergio Fausto said that Vargas's labor policy was very clear. Between 1930 and 1945, it changed several times. But from the start, it was new compared to what came before. Its main goals were to stop city workers from organizing outside government control. It also aimed to bring workers into the government's group of supporters. To do this, Vargas created the Ministry of Labor, Industry, and Commerce in November 1930. He named Lindolfo Collor as the first Minister of Labor.

Laws were passed to protect workers. A decree in March 1931 brought unions under government control. Vargas's government also set up Bureaus of Reconciliation and Arbitration. These groups helped solve problems between workers and bosses. To protect Brazilian workers, the government limited immigration. It also required that at least two-thirds of all workers in any factory had to be Brazilian. The President gained a lot of support from organized labor. His government started building promised housing for workers in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. However, these homes were not enough for the growing population. He also started taking strong actions against leftist groups, especially the Brazilian Communist Party.

The economic rules Vargas put in place were still being avoided as late as 1941. Large businesses in big towns could not avoid minimum wage laws. But the minimum rural salary of 1943 was often not followed by employers. In fact, many social policies never reached rural areas. Each state was different. Social laws were enforced less by the government and more by the kindness of employers and officials in distant parts of Brazil.

Vargas's laws helped industrial workers more than the larger number of farm workers. Even so, only a few industrial workers joined the unions the government encouraged. The state-run social security system was not very good. The Institute for Retirement and Social Welfare did not achieve much. People were unhappy about these problems. This was shown by the growing popularity of the National Liberation Alliance, a leftist group, in 1935. Also, the Faustos said, "The nation's financial situation became very bad in mid-1931." Payments on Brazil's foreign debt stopped in September of that year. The Bank of Brazil was again given the only right to exchange currency. This rule had been put in place by President Luís's government but was removed by Vargas's provisional government.

Religion and Education

Brazil had a close relationship between the church and the state when Vargas took power. This cooperation mostly started in the 1920s. Vargas made this relationship even closer. This was clear when the statue of Christ the Redeemer was unveiled on October 12, 1931. Vargas and his ministers were there. Cardinal Leme, who helped remove President Luís, declared Brazil "the most holy heart of Jesus."

Vargas's government took special steps to help the church. The church supported the new government. In April 1931, a decree allowed religion to be taught in public schools. Vargas himself was not religious, though his wife Darci was Catholic. He even named his first son Lutero, which is not a Catholic name. His goal for joining the church and state was to gain popular support for his government. He wanted to use religious feelings to support the state.

Vargas's government also wanted to improve education. They immediately introduced new plans. Like religion, education reform was first tried in the 1920s at the state level. But Vargas's new government wanted to centralize education. They created the Ministry of Education and Health in November 1930. The plans were based on "authoritarianism." They combined strict values with Catholic traditions. But it was never seen as "fascist teaching." Big changes also happened in higher education. Vargas's government created good conditions for universities.

However, Vargas's reforms were limited. Even though his laws existed, they were not always enforced well. In 1948, Anísio Teixeira, a famous Brazilian education reformer, looked at education reform in Bahia. He gave a speech on April 16, 1948. He said that most education efforts were done by primary school teachers in cities or rural areas. In rural areas, there were often no school buildings, only temporary classrooms. There were almost no teaching materials. He also noted that there were few state-funded high schools. Despite these problems, there were still many dedicated teachers.

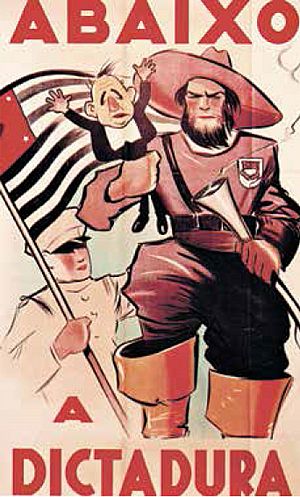

Resistance to Change

The change from the Old Republic to a new system was hard, even with Vargas's reforms. A rebellion broke out in Recife in May 1931. Vargas's advisors suggested declaring martial law. Vargas told them to rewrite it. One advisor said Vargas had a "passive resistance" that was frustrating. Vargas gained more support from senior army officers. But bloody riots happened in Recife in October 1931. In February 1932, the Democratic Party of São Paulo joined forces with Republicans. They formed a united front against Vargas. There was even a group in Vargas's home state of Rio Grande do Sul. They pushed for individual rights, freedom of the press, and a new election. At this point, some foreign diplomats doubted Vargas was in control. They saw division among revolutionary leaders and unrest in the country.

The difficult change was most clear in the 1932 Constitutionalist Revolution. This was a three-month civil war in Brazil. It lasted from July 9 to October 2, 1932. São Paulo fought against the federal government. São Paulo was unhappy because its interests were lost. They wanted a free constitution. Also, São Paulo was upset that Vargas had replaced their state presidents with his own "interventors." São Paulo's interventor, João Alberto Lins de Barros, was very unpopular. He was forced to resign in July 1931 after a small rebellion. Three different interventors followed him until mid-1932.

São Paulo believed Minas Gerais and Rio Grande do Sul would join them. They hoped for a coup. But this did not happen. Vargas felt sad during the crisis. Both his daughter Alzira and a close friend noted he was going through a difficult time. Federal forces defeated the revolutionaries. But a new constitution was created two years later. Vargas, however, gave easy peace terms. He ordered the federal government to pay half of the rebels' debt. He refused to bomb or invade the city of São Paulo. Instead, fighting was limited to the city's edges. Vargas was always at risk of being removed by groups in his government. Rumors of coups from both left and right sides spread during his provisional presidency.

Electoral Reform and the 1934 Constitution

Under Vargas's rule, the government was responsible for protecting the secret vote in elections. Many voting changes were made. These included creating the Electoral Justice. This group organized and watched over elections. Women's suffrage was also introduced, giving women the right to vote. The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18. These changes reduced fraud.

Before the São Paulo revolt, Vargas promised to hold elections. He made this promise in a speech in May 1932. In the same speech, he talked about the achievements of his provisional government. These included education reform and a balanced budget. He compared Brazil's situation to England and France. He said emergency powers were needed during an economic crisis. Vargas kept his promise. In May 1933, elections were held for a National Constituent Assembly. More people voted, and political parties became better organized. The Communist Party was banned. Many parties appeared in different states. There were no national parties, except for the right-wing Brazilian Integralist Action.

The Constituent Assembly was elected under Vargas's provisional presidency. It met from 1933 to 1934. After months of discussion, they created a new Constitution for Brazil. It was the third in the country's history. It guaranteed a fair court system, government responsibility for the economy, and general welfare. Like the Constitution of 1891, it set up a federal republic in Brazil. It was based on Germany's Weimar Constitution. The new constitution reflected Vargas's earlier reforms. It dealt with minimum wage, workers' rights, and free primary schools. It also included religion classes (optional in public schools) and national security. The constitution became law on July 14, 1934. The Constituent Assembly then elected Vargas on July 15. He was elected to a four-year term to continue as president. His constitutional presidency was set to end on May 3, 1938. Historian Thomas Skidmore said about Vargas's change to a new system: "It looked as if Brazil was finally going to be allowed an experiment in modern democracy."

Towards a Dictatorship

Authoritarian Direction

Vargas had offered Luís Carlos Prestes a military leadership position in 1930. But Prestes refused. He chose to lead the Brazilian Communist Party. The Communist Party had a problem. Their ideas focused on city workers. But Brazil was still a farming society. Many city workers came from rural areas and did not want to join. Workers who did join were hard to organize. Still, politicians and generals were afraid. Strong actions were taken against communists. On January 19, 1931, Vargas ordered that any communists be arrested and their property taken.

Communists held marches and street fights, similar to what was happening in Europe. The Communist Party hoped a military coup would overthrow the Brazilian government. They thought this would weaken the United States and the United Kingdom. It would also strengthen the Soviet Union. In November 1935, there were uprisings at military bases in Natal, Recife, and Rio de Janeiro. This led to the communist uprising of 1935. The Communist International believed they had enough people in the army to help Prestes with the coup. But Vargas's forces "crushed" all the revolts. In reality, the uprising helped Vargas. The Communist Party did not know they were being watched by Brazilian police. Their attack gave proof of a "Bolshevik threat."

Skidmore said that Vargas's government used the revolt for propaganda. They spread greatly exaggerated stories about loyal officers being shot in their beds. These stories were later proven false by military records. Right after the revolt, Vargas convinced Congress to declare a state of emergency. During this time, he stopped civil rights. He jailed trade union members and his opponents. He increased presidential powers and police powers. For the next two years after the 1935 revolt, Vargas kept convincing Congress to renew the state of siege every 90 days. During this time, the government had special police powers. There were growing worries that Vargas was planning to take full power himself. Prestes was also jailed in 1936. He was sentenced to over 16 years in prison. He was later released in 1945 and supported Vargas's policies that same year.

Coup of 1937

Fears that Vargas would take full power grew. His top generals, Pedro Aurélio de Góis Monteiro and Minister of War Eurico Gaspar Dutra, were authoritarian and admired Germany. Vargas became more dependent on the military for support. Political attention turned to the 1938 presidential elections. Vargas's opponents began to support Armando Salles de Oliveira. He was a member of the São Paulo elite. Skidmore said they were "now trying to gain through the vote what they had failed to gain by arms in 1932." Vargas's government supported a writer from the Northeast, Jose Americo de Almeida. But the São Paulo group was confident. They sought and received support from those against Vargas.

All the while, Vargas's power was weakening. Political discussions allowed some strict rules to be loosened. Three hundred people were released from prison by order of the Minister of Justice. Vargas and his government did not trust any of the three candidates. One government observer even thought Brazil was at risk of a civil war, like Spain. Leading up to the coup that would make Vargas a dictator, he was somewhat sad. He never seemed to admit he enjoyed his power. However, after a meeting with Monteiro and J. S. Maciel Filho, the President became reenergized. This was clear from his journal entries, though he was still saddened by the upcoming elections. One week before the coup, Vargas celebrated the seventh anniversary of his rise to power. He spent the evening in a "long" conversation with Monteiro.

The reason given for the coup was the Cohen Plan. This was a document found in September 1937 at the Ministry of War. It described plans for a violent communist uprising. In reality, the document was a clear fake. After the Cohen Plan was revealed, the coup happened on November 10, 1937. All but one cabinet member signed the new constitution as Vargas requested. Military troops surrounded the National Congress and stopped congressmen from entering. The 1937 Constitution, which was corporatist and totalitarian, was now in force. The 1938 presidential elections were canceled. Brazil became a dictatorship called the Estado Nôvo, or New State, led by Vargas. The National Congress agreed after some congressmen were jailed. Eighty lawmakers went to see Vargas to show support on November 13. Meanwhile, life in Brazil went on as usual. The people accepted the change calmly.

Establishing the Dictatorship

Vargas's main opponents were either arrested or sent out of the country. Censorship hid information from the media. The police were given more power. The public became quiet. Just like when he first took office, Vargas ruled by decree. The Integralists first supported the coup. They liked the move towards right-wing politics. They expected their leader, Plínio Salgado, to be offered a cabinet job, especially Minister of Education. But the opposite happened. Vargas's government put new limits on their activities. In response, a group of Integralists tried to overthrow the government themselves.

From May 10 to 11, 1938, armed Integralists and disloyal palace guards attacked the presidential palace. They tried to remove Vargas from power. They started shooting at the building where Vargas was sleeping. This led to a siege lasting many hours, with Vargas and his daughter Alzira inside. Federal reinforcements arrived to help Vargas. Four attackers were killed, and the rest were jailed. Salgado went into exile in Portugal. This incident caused a temporary cooling in relations between Germany and Brazil.

Most of the constitution was written by one man, Francisco Campos. He was against liberalism and communism. He later became Vargas's Minister of Justice. The new constitution was very detailed. Campos had worked quickly. For example, Article II said there should be only one flag, song, and motto across the country. Campos later held a press conference. He announced the creation of the National Press Council. This group was made to "perfectly coordinate with the government in controlling news and political material." In general, the new era included parts of European fascism. But the President relied on the army for support, not political parties. Being against liberalism was also very clear.

Vargas outlawed all political parties on December 2, 1937. A public vote to approve the new government was canceled. The planned congress never met. Vargas's term was extended by six years. Personally, Vargas told foreign reporters that the Estado Nôvo was democratic at heart. But it promoted authoritarianism at home. When Alzira asked him about the public vote, Vargas replied that the coup was meant to avoid elections. Industrial growth happened, and support for coffee decreased. Campos had suggested a totalitarian party. The Minister of Education asked for a fascist youth program. Vargas showed little interest in both ideas and stopped them. "Brasilidade" led to changes in Portuguese spelling. Foreign language schools and newspapers were closed. German and Italian communities were the main targets. But it never reached the level of Nazi Germany. When it came to important issues, Vargas's personal power was the deciding factor. Trust between the President and his ministers grew. Between March 1938 and June 1941, there were no changes in ministers.

Nationalism and Domestic Policy as Dictator

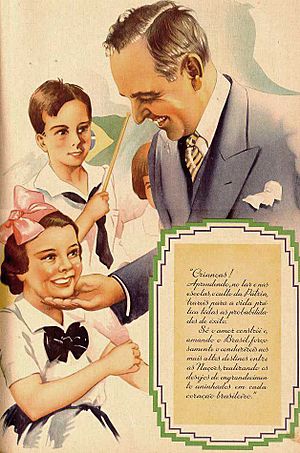

Historian Teresa Meade said that Vargas's major social reforms helped him gain the loyalty of city workers. These reforms included a minimum-wage law and combining all labor reforms since 1930 into one labor act. These labor laws also focused on corporatism. Vargas's image as the "workers' guardian" became strong. This was clear at events like the May Day celebration, where many people gathered. He used the radio to connect workers and the government. The labor minister gave weekly radio speeches.

From 1930 to 1938, the wage index rose from 230 to 315 points. However, the cost of living also increased. It went from 290 to 490 points. The cost of living doubled in Rio de Janeiro and almost tripled in São Paulo. But Brazil recovered from the Great Depression faster than the United Kingdom or the United States. This recovery was helped by World War II production, American technology, and Brazilians buying from Brazilian producers when shipping was interrupted. Starting in 1935, business owners wanted to build oil refineries in Brazil. Companies like Standard Oil (1936) and Texaco (1938) built large refineries. But these were taken over by the Brazilian government in April 1938. The President also stopped paying the national debt right after the coup. He said Brazil could either modernize its military and transportation or pay the debt.

Popular culture was also important during Vargas's dictatorship. In 1941, his government created the National Sport Council. Skidmore said Vargas was one of the first politicians to see the political benefit of supporting sports. Another example was the Rio Carnival. Vargas's government was the first to support samba schools and Rio parades at the federal level. Both became symbols of Brazilian culture. This led to two good things: economic benefit (tourism) and a stronger national identity. Also, Vargas's government started a big project to restore old buildings, sculptures, and paintings. In Petrópolis, the Imperial Museum of Brazil was restored. The Ministry of Education and Culture building in Rio de Janeiro was designed by a French architect. A darker side of Vargas's national identity work was to protect the country from those seen as "un-Brazilian." This included Japanese Brazilians or Jewish Brazilians. There was official and unofficial discrimination. This was mainly limited to closing "foreign" newspapers, schools, and organizations. But it never reached the level of Nazi Germany.

Wartime Leader and Fall

Foreign Policy Before the War

In Europe, Nazi Germany saw Brazil as a key trading partner. From 1933 to 1938, trade between Germany and Brazil grew a lot. Germany mainly bought Brazilian cotton. In return, Brazil received German industrial goods. The United Kingdom lost out on this trade. Germany hoped to bring Brazil into its political and military influence. They sold weapons to Brazil and offered training. The 1937 coup was praised in Germany and Italy. However, the U.K. also played a big role in helping Vargas's police and intelligence. British agents gave information on foreign threats. They also helped Brazil during the 1935 communist uprising.

After the 1937 coup, the United States immediately asked Brazil's ambassador, Aranha, for an explanation. The U.S. knew Brazil's important location on the Atlantic coast. It could play a key role in controlling air and sea travel. The American military worried the coup would bring Brazil closer to Nazi Germany. They knew Vargas's advisors, especially Dutra and Monteiro, had pro-German views. The U.S. had been trying to influence Brazil but struggled. The large German-speaking population in Southern Brazil increased American fears about Vargas's dictatorship. Under U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the United States started the Good Neighbor policy towards Latin America. This was like a modern Monroe Doctrine. Similar to before World War I, the U.S. State Department also spoke out against German trade policy. The military tried to offer weapons and training to counter German offers, but they failed. Vargas had actually tried to get U.S. military equipment first. But the United States Congress, which wanted to stay out of foreign conflicts, refused. They even made foreign arms sales illegal.

In 1937, Vargas offered U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt the use of Brazilian coastal bases. But the offer was refused. This was likely because Roosevelt had to follow Congress or go against them. Accepting the offer would have looked like he was preparing for war. In 1938, Vargas sent Aimée de Heeren to Paris as a secret agent. She was to investigate the situation in Europe. Through Helmuth James von Moltke, she got secret information about Hitler's plans for the Jewish population. This made her use "all her influence" on the President to move Brazil away from the Axis powers. In 1939, at the start of World War II, Vargas and Roosevelt both stayed neutral. But Vargas continued to build relations with the Axis powers. By 1941, Vargas still kept his options open. He approved a plan to modernize airports in North and Northeast Brazil. This was done by Pan American Airways under a contract with the U.S. army.

World War II and the End of the First Presidency

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States, it became clear that Brazil's military chances were better with the Allies of World War II. This was made stronger by Germany's terrible 1941 Invasion of Russia and their losses in the Atlantic. Also, the U.S. was already forming alliances with Brazil. An important trade deal in 1939 and the sale of 90 six-inch guns to Brazil in March 1940 focused foreign policy on the U.S. With this, Brazil declared war on Italy and Germany on August 21, 1942. This followed torpedo attacks on Brazilian ships and the sinking of a Brazilian submarine that year. Brazil provided the allies with raw materials and its important coastline. Siding with the allies led to Monteiro and Dutra offering to resign. But the President refused their resignations. Vargas also made a good deal. In exchange for raw materials, the U.S. military provided equipment, technical help, and money for a Brazilian steel mill at Volta Redonda. This was finalized in July 1940.

Vargas wanted Brazil to be clearly on the Allied side. He offered three Brazilian army divisions to fight the Germans in the Mediterranean. This was to highlight Brazil's role in the war and boost Brazilian pride at home. Also, a group from the army fought important battles in the Italian campaign in 1944. This further increased war pride and anti-fascism. Vargas insisted that every state be represented in the army. His government now had even more power. This was because essential goods needed to be rationed, and centralization continued in Brazil.

When World War II ended, there was growing unhappiness in Brazil. This was despite the government defending democracy abroad. People were unhappy with Vargas's authoritarian policies. Growing political movements and democratic protests forced Vargas to end censorship in 1945. He released many political prisoners. He also allowed political parties to form again, including the Brazilian Communist Party, which supported Vargas. University students started protesting against Vargas in 1943. Strikes, which were banned, began again due to war inflation. Even Aranha supported a move towards democracy. Vargas himself gained support after creating the Brazilian Labour Party. He also found help from the left.

Vargas added an Additional Act to the constitution. This act set a 90-day period to announce the date for elections. Exactly 90 days later, the new election rules were issued. They set December 2, 1945, for the election of the president and a new assembly. State elections were set for May 6, 1946. Vargas also said he would not run for president. The military feared Vargas was about to take absolute power. This fear grew after he removed João Alberto from police chief and replaced him with Vargas's brother Benjamin on October 25, 1945. So, the military forced Vargas to resign. They removed him from power on October 29, ending his first presidency.

Between Presidencies

In the 1945 elections, Vargas showed he still had popular support. He won elections as a senator for São Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul. He also became a member of the chamber of deputies from nine different states. He accepted the senate seat for Rio Grande. But he mostly went into semi-retirement. In 1950, he returned as a major political force. He ran for president as the candidate of the Brazilian Labor Party. He won the election and took office on January 31, 1951.

Second Presidency (1951–1954)

When Vargas left the Estado Novo presidency, Brazil had a large economic surplus. Its industry was growing. However, after four years, the pro-U.S. President Dutra wasted a lot of money protecting foreign investments. Most of these were North American. Dutra moved away from Vargas's ideas of nationalism and modernizing the country. Vargas returned to politics in 1951. He was re-elected president through a free and secret vote.

His presidency was difficult due to an economic crisis. This crisis was largely caused by Dutra's policies. Vargas followed a nationalist policy. He focused on Brazil's own natural resources and moved away from relying on other countries. As part of this policy, he founded Petrobras (Brazilian Petroleum). This was a large oil company. The Brazilian government was its main owner.

Death

Vargas's political enemies created a crisis. This led to the murder of an Air Force officer, Major Rubens Vaz. Lieutenant Gregório Fortunato, Vargas's personal guard, was involved in the crime. This made the military angry at Vargas. The generals demanded his resignation. Vargas called a special cabinet meeting on the night of August 24. But rumors spread that the military officers would not change their minds.

At 8:45 AM on Tuesday, August 24, 1954, at the Catete Palace, Vargas shot himself in the chest with a pistol. He could not handle the situation.

His death note was found. It was read on the radio within two hours of his son finding the body. The famous last lines said, "Serenely, I take my first step on the road to eternity. I leave life to enter History." That same day, riots broke out in Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre.

The Vargas family refused a state funeral. But his successor, Café Filho, declared official days of mourning. Vargas's body was shown to the public in a glass-topped coffin. Tens of thousands of Brazilians lined the route as his body was carried from the Presidential Palace to the airport. The burial and memorial service were in his hometown of São Borja, Rio Grande do Sul.

The Museu Histórico Nacional (MHN) received the furniture from the bedroom where Vargas died. A museum gallery recreates the scene. It is a place for remembrance. His nightshirt with a bullet hole is on display in the Palace. The public's anger caused by his death was strong. It supposedly stopped the plans of his enemies for several years. These enemies included right-wing groups, anti-nationalists, pro-U.S. groups, and even the pro-Prestes Brazilian Communist Party.

Legacy

Many historians see Vargas as the most important Brazilian politician of the 20th century. He was also the first to gain wide support from ordinary people. He fought against the influence of the elite. Vargas led Brazil through the Great Depression. He was called "the Father of the Poor" because of his economic reforms.

See also

In Spanish: Getúlio Vargas para niños

In Spanish: Getúlio Vargas para niños

- History of Brazil (1930–1945)

- History of Brazil (1945–1964)

- Fundação Getúlio Vargas

- Brazilian Integralism

- Tonelero Street

- Vargas diamond

Images for kids

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |