Luis Federico Leloir facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Luis Federico Leloir

|

|

|---|---|

An early photograph of Leloir in his twenties

|

|

| Born | September 6, 1906 |

| Died | December 2, 1987 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | |

| Alma mater | University of Buenos Aires |

| Known for | Galactosemia Lactose intolerance Carbohydrate metabolism |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry |

| Institutions | University of Buenos Aires Washington University in St. Louis (1943-1944) Columbia University (1944-1945) Fundación Instituto Campomar (1947-1981) University of Cambridge (1936-1943) |

Luis Federico Leloir (born September 6, 1906 – died December 2, 1987) was an amazing Argentine doctor and biochemist. He won the 1970 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He earned this prize for finding out how our bodies make and use carbohydrates (sugars and starches) for energy.

Even though he was born in France, Leloir studied mostly at the University of Buenos Aires. He became the director of a special research group called Fundación Instituto Campomar. He led this group until he passed away in 1987. His research on sugar, how the body uses carbohydrates, and kidney problems helped scientists a lot. His work led to big steps in understanding and treating a disease called galactosemia. Luis Leloir is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires.

Contents

Biography

Early life and interests

Luis Leloir's parents traveled from Argentina to Paris in 1906. His father was very sick. Sadly, his father died in August, and Luis was born a week later in Paris. In 1908, his family moved back to Argentina. He grew up with his eight brothers and sisters on a huge family property. This land was along the coast and is now a popular tourist spot.

As a child, Luis loved watching nature. His schoolwork and books showed him how science and biology were connected. He went to different schools, including one in England for a few months. He wasn't always the best student. He even tried studying architecture in Paris but soon realized it wasn't for him.

In the 1920s, Leloir invented "salsa golf" (golf sauce). He was having lunch with friends and wanted to make his prawns taste better. So, he mixed ketchup and mayonnaise. Later, when his lab had money problems, he would joke about it. He'd say, "If I had patented that sauce, we'd have a lot more money for research right now!"

Starting his career

In Buenos Aires

After returning to Argentina, Leloir became an Argentine citizen. He joined the Department of Medicine at the University of Buenos Aires. He wanted to get his doctorate degree. He found his anatomy exam quite challenging, needing a few tries to pass. He finally got his diploma in 1932. He then started working in hospitals. After some challenges in treating patients and working with others, Leloir decided to focus on laboratory research.

In 1933, he met Bernardo Houssay, a famous scientist. Houssay encouraged Leloir to study the suprarenal glands and how the body uses carbohydrates for his doctoral project. Houssay would later win the Nobel Prize himself in 1947. Leloir and Houssay became very close friends. They worked together on many projects until Houssay's death in 1971. Leloir later said that Houssay influenced his entire research career.

Studying in Cambridge

After only two years, Leloir's doctoral project was recognized as the best by the University of Buenos Aires. He felt he needed to learn more about physics, mathematics, chemistry, and biology. So, he kept taking classes part-time. In 1936, he went to England to study at the University of Cambridge. He worked with another Nobel Prize winner, Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins. Hopkins had won his prize for finding out how important vitamins are for health. In Cambridge, Leloir studied enzymes and how the body uses carbohydrates.

Time in the United States

Leloir came back to Buenos Aires in 1937. In 1943, he got married to Amelia Zuberbuhler. They later had a daughter, also named Amelia. However, his return to Argentina happened during difficult political times. His mentor, Houssay, had been removed from the University of Buenos Aires. This was because Houssay had signed a public letter against the military government.

Leloir then went to the United States. He worked at Washington University in St. Louis and later at Columbia University. He worked with other famous scientists there. Leloir later said that working with David E. Green made him want to start his own research lab in Argentina.

Leading his own research

Fundación Instituto Campomar

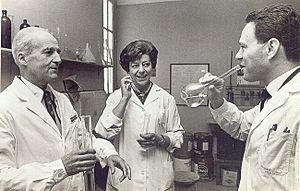

In 1945, Leloir returned to Argentina. He started working with Houssay again. In 1947, a businessman named Jaime Campomar helped create the Instituto de Investigaciones Bioquímicas de la Fundación Campomar. Leloir became its director.

At first, the institute was small, with only five rooms. They didn't have much money or expensive equipment. But Leloir and his team still did amazing experiments. They found out how sugar is made in yeast and how fats are used for energy in the liver. They even figured out how to study cells outside of a living body. This was a big deal! They didn't have a fancy machine to separate cell parts. So, they used a car tire filled with salt and ice to spin things around.

By 1947, Leloir had a great team. They studied why a kidney problem and a substance called angiotensin can cause high blood pressure. That same year, his colleague Ranwel Caputto discovered how carbohydrates are stored and turned into energy in the body.

Discovering sugar nucleotides

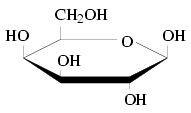

In 1948, Leloir and his team made a huge discovery. They found "sugar nucleotides." These are special molecules that are key to how carbohydrates are used in the body. This discovery made the Instituto Campomar famous worldwide. Leloir and his team also figured out how the body processes galactose, a type of sugar. This helped them understand the cause of galactosemia. This is a serious genetic disorder that makes people unable to properly digest lactose, the sugar in milk.

The next year, Leloir helped create a new Biochemical Institute at the University of Buenos Aires. This institute helped develop science programs in other Argentine universities. It also attracted scientists from many countries, including the United States, Japan, and England.

After Jaime Campomar died in 1957, Leloir's team needed money. They got funding from the National Institutes of Health in the United States. In 1958, the institute moved to a new, bigger building. It was a former all-girls school donated by the Argentine government. As Leloir's work became more well-known, they received more research money. The institute also became connected with the University of Buenos Aires.

Later years and legacy

In his later years, Leloir continued to study glycogen and other ways the body uses carbohydrates. He kept teaching at the University of Buenos Aires. He only took breaks to study in Cambridge and the United States. In 1983, Leloir helped start the Third World Academy of Sciences, now called the TWAS.

Winning the Nobel Prize

On December 2, 1970, Luis Leloir received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. The King of Sweden gave him the award. He was honored for his discoveries about how the body uses lactose and other carbohydrates. He was only the third Argentine to win a Nobel Prize at that time.

In his acceptance speech, he joked, "never have I received so much for so little." Leloir and his team reportedly celebrated by drinking champagne from test tubes. This was unusual for them, as Leloir was known for being humble and careful with money.

His lasting impact

Leloir wrote a short autobiography called "Long Ago and Far Away." He died in Buenos Aires on December 2, 1987, from a heart attack. He is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery.

A friend of Leloir, Mario Bunge, said that Leloir's biggest legacy was proving something important. He showed that top-level scientific research was possible even in a developing country with political problems. Leloir was very determined. When his lab had money troubles, he often made his own tools. Once, he even used waterproof cardboard to make gutters. This was to protect his lab's library from the rain!

Leloir was known for being humble, focused, and consistent. Many called him a "true monk in science." Every morning, his wife Amelia would drop him off at the lab. He always wore the same old gray overalls. He worked for decades sitting on the same straw seat. He encouraged his colleagues to eat lunch at the lab to save time. He would even bring enough meat stew to share with everyone. Even though he was very careful with money and dedicated to his research, he was a friendly person. He said he didn't like working alone.

The Fundación Instituto Campomar has since been renamed Fundación Instituto Leloir. It has grown a lot. It is now a large building with many researchers and staff. The Institute continues to do important research. This includes studies on diseases like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and multiple sclerosis.

Awards and distinctions

| Year | Distinction |

|---|---|

| 1943 | Third National Science Award |

| 1958 | T. Ducett Jones Memorial Award |

| 1960 | Elected an International Member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences |

| 1961 | Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences |

| 1963 | Elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society |

| 1965 | Bunge and Born Foundation Award |

| 1966 | Gairdner Foundation Award |

| 1967 | Columbia University's Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize |

| 1968 | Benito Juárez Award |

| 1968 | Honorary Doctorate from Universidad Nacional de Córdoba |

| 1968 | Argentina Chemistry Association's Juan José Jolly Kyle Award |

| 1969 | Honorary member of the English Biochemical Society |

| 1970 | Nobel Prize in Chemistry |

| 1971 | Legion de Honor “Orden de Andrés Bello” |

| 1972 | Elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1972 |

| 1976 | Grand Cross of the Order of Bernardo O'Higgins (Chile) |

| 1982 | Legion of Honour |

| 1983 | Diamond Konex Award: Science and Technology |

See also

In Spanish: Luis Federico Leloir para niños

In Spanish: Luis Federico Leloir para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |