Mangosuthu Buthelezi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Honourable Prince

Mangosuthu Buthelezi

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

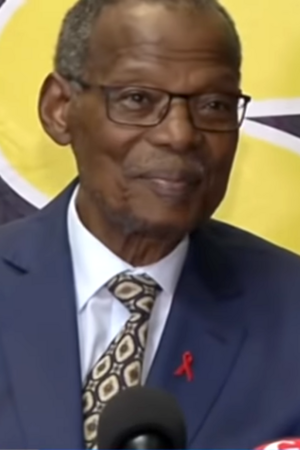

Buthelezi in 2019

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Home Affairs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 1994 – 13 July 2004 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Danie Schutte | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the National Assembly of South Africa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 29 April 1994 – 8 September 2023 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituency | KwaZulu Natal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the Inkatha Freedom Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 21 March 1975 – 25 August 2019 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Velenkosini Hlabisa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi

27 August 1928 Mahlabathini, Natal, Union of South Africa |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 9 September 2023 (aged 95) South Africa |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | IFP | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Irene Audrey Thandekile Mzila

(m. 1952; died 2019) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 8, including Sibuyiselwe Angela | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residences | Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Known for | Founder of the IFP (1975) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House | Zulu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Anglican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi (born August 27, 1928 – died September 9, 2023) was an important South African politician and a Zulu prince. He was a Member of Parliament and served as the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family from 1954 until his death. He was appointed to this role by King Cyprian Bhekuzulu, who was his cousin.

Buthelezi was also the Chief Minister of the KwaZulu bantustan (a special area set aside for black people) during the time of apartheid. He started the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) in 1975 and led it until 2019. After that, he became its President Emeritus. From 1994 to 2004, he was the Minister of Home Affairs for South Africa.

Buthelezi was a very well-known black politician during the apartheid era. He led the KwaZulu government from 1970 until it ended in 1994. He also held the title of Inkosi (chief) of the Buthelezi clan. He was the traditional prime minister to three Zulu kings. Buthelezi himself was born into the Zulu royal family. His great-grandfather was King Cetshwayo kaMpande, whom he played in the 1964 film Zulu.

While leading KwaZulu, Buthelezi helped make the Zulu monarchy stronger. He used it as a symbol of Zulu pride and identity. With support from the royal family and government resources, his political group, Inkatha (now the IFP), became one of the biggest in the country.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Mangosuthu Buthelezi was born on August 27, 1928. His birthplace was Mahlabathini, in the Natal province of South Africa. His father was Chief Mathole Buthelezi. His mother was Princess Magogo kaDinuzulu, who was the sister of King Solomon kaDinuzulu.

He went to Impumalanga Primary School from 1933 to 1943. Then he studied at Adams College from 1944 to 1947.

Mangosuthu attended the University of Fort Hare from 1948 to 1950. There, he joined the African National Congress Youth League. He met other future leaders like Robert Mugabe and Robert Sobukwe. He was later asked to leave the university after student protests. He finished his degree at the University of Natal.

Becoming a Leader

Buthelezi became the chief of the large Buthelezi tribe in 1953. He held this important position for the rest of his life.

In 1963 and 1964, he helped with the film Zulu. This movie was about the Battle of Rorke's Drift. Buthelezi also acted in the film. He played his own great-grandfather, King Cetshwayo kaMpande.

In 1970, Buthelezi was made the leader of the KwaZulu area. By 1976, he became the chief minister of the Bantustan of KwaZulu. Some people criticized him for working within the apartheid system. However, he always refused to accept full independence for KwaZulu. He waited until Nelson Mandela was released from prison. He also waited until the African National Congress (ANC) was allowed to operate again.

Founding the Inkatha Freedom Party

In 1975, Buthelezi started the Inkatha National Cultural Liberation Movement. He had the support of the African National Congress (ANC) at first. Oliver Tambo, the ANC leader in exile, encouraged him to restart this cultural movement.

However, by 1979, his relationship with the ANC became difficult. Inkatha and the ANC disagreed on how to fight apartheid. The ANC favored using military action, through its group called Umkhonto we Sizwe. Buthelezi and Inkatha preferred non-violent methods. A meeting in London between the two groups did not solve their differences.

In 1982, Buthelezi spoke out against the government's plan to give the Ingwavuma region to Swaziland. The courts agreed with him. They said the government had not followed its own rules. He also helped set up colleges for teachers and nurses in the 1970s and 1980s. He asked his friend Harry Oppenheimer to help create Mangosuthu Technikon in Umlazi.

Working for Peace and Change

On January 4, 1974, Buthelezi met with Harry Schwarz, a leader from the Transvaal. They signed the Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith. This agreement outlined a five-point plan for peace in South Africa.

The declaration called for talks involving all people. It aimed to create a new constitution. This constitution would protect everyone's rights with a Bill of Rights. It also suggested that a federal system would be best for South Africa. Most importantly, it stated that political change should happen peacefully.

This declaration was the first time black and white leaders in South Africa agreed on these ideas. It showed a commitment to peaceful change when many others were not seeking dialogue. Many people praised it as a big step forward in race relations. Other black homeland leaders also supported the declaration.

Negotiations to End Apartheid

Buthelezi played a complex role in the talks to end apartheid. He helped set the stage for these talks as early as 1974. During the Congress for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA), the IFP wanted a federal system. This would give strong powers to different regions and protect the status of Zulu traditional leaders.

However, this idea was not accepted. Buthelezi felt that the IFP and he were being left out of the talks. The African National Congress (ANC) and the white National Party government became the main negotiators. Buthelezi then formed a group with other conservative leaders. He pulled out of the talks and planned to boycott the 1994 general election. This was South Africa's first election where everyone could vote.

Despite fears that Buthelezi might stop the peaceful change, he and the IFP decided to join the election at the last minute. They also joined the Government of National Unity. This government was formed by the new President, Nelson Mandela. Buthelezi served as Minister of Home Affairs under Mandela and later under Thabo Mbeki. This happened even though there were often disagreements between the IFP and the ANC.

In later years, the IFP found it hard to gain support outside of KwaZulu-Natal. This province had absorbed KwaZulu in 1994. As the party's support decreased, Buthelezi faced challenges from rivals within his party. He remained the IFP's president until August 2019. He then chose not to run for re-election. Velenkosini Hlabisa became his successor. In the 2019 general election, Buthelezi was elected as a Member of Parliament for the IFP for the sixth time.

Key Roles and Positions

Buthelezi held many important positions throughout his life:

- Chief Executive Officer of the Zulu Territorial Authority (1970–1972).

- Chief Executive Councillor of the KwaZulu Government (1972–1977).

- President of the Inkatha Freedom Party (1975–2019).

- Chief Minister of the KwaZulu Government (1977–1994).

- Member of the National Assembly of South Africa (since 1994).

- South African Minister of Home Affairs (1994–2004).

- Chairman of the South African Black Alliance. This group included several political parties.

- Chancellor Emeritus of the University of Zululand.

- Member of the University of KwaZulu-Natal Foundation.

- Chairman of Traditional Leaders in the KwaZulu-Natal Legislature.

- Traditional Prime Minister of the Zulu Nation.

Awards and Recognition

Buthelezi received many awards for his leadership and work:

- King's Cross Award from King Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu (1989).

- Key to the City of Birmingham, Alabama (1989).

- Freedom of Ngwelezana (1988).

- Unity, Justice and Peace Award by Inkatha Youth Brigade (1988).

- Magna Award for Outstanding Leadership from Hong Kong (1988).

- Honorary Freedom of the City of Pinetown, Kwazulu-Natal (1986).

- Honorary LLD from Boston University (1986).

- Nadaraja Award by Indian Academy of SA (1985).

- Man of the Year by Financial Mail (1985).

- Newsmaker of the Year by Pretoria Press Club (1985).

- Honorary LLD from Tampa University, Florida (1985).

- Apostle of Peace (Rastriya Pita) by Pandit Satyapal Sharma of India (1983).

- George Meany Human Rights Award by the AFL-CIO (1982).

- French National Order of Merit (1981).

- Honorary LLD from University of Cape Town (1978).

- Citation for Leadership by District of Columbia Council, USA (1976).

- Honorary LLD by Unizul (1976).

- Knight Commander of the Star of Africa for Outstanding Leadership by President Tolbert of Liberia (1975).

- Newsmaker of the Year by SA Society of Journalists (1973).

- Man of the Year by Institute of Management Consultants of SA (1973).

Personal Life

Buthelezi married Irene Audrey Thandekile Mzila (1929–2019). They met in January 1949 and married on July 2, 1952. They had eight children: three sons and five daughters. At the time of Irene's death in 2019, three of their children were still alive.

Buthelezi was a member of the Anglican Church. He chose to have only one wife, following Christian beliefs. His traditional home was in kwaPhindangene in Ulundi. He enjoyed classical and choral music.

He passed away on September 9, 2023, at the age of 95.

See also

In Spanish: Mangosutu Buthelezi para niños

In Spanish: Mangosutu Buthelezi para niños