Maria Janion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maria Janion

|

|

|---|---|

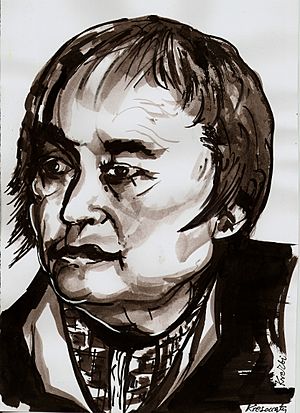

Maria Janion, portrait by Zbigniew Kresowaty

|

|

| Born | 24 December 1926 Mońki, Poland

|

| Died | 23 August 2020 (aged 93) Warsaw, Poland

|

| Occupation | literary critic |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | University of Warsaw |

| Academic work | |

| Notable works | The Project of Phantasmatic Criticism (1991) Romanticism, Revolution, Marxism (1972) |

Maria Janion (born December 24, 1926 – died August 23, 2020) was a famous Polish expert in literature. She was a professor and a literary critic, meaning she studied and wrote about books. Maria Janion was also a feminist, someone who believes in equal rights for women. She specialized in a style of literature called Romanticism. She was a respected member of important Polish academies and received a special honorary degree from Gdańsk University.

Contents

Life and Career Highlights

Maria Janion was born on December 24, 1926, in Mońki, Poland. She lived in Vilnius until 1945, where she finished high school. During World War II, she was a member of the Polish Scouting and Guiding Association. She worked as a liaison officer, helping to pass messages. After the war, her family moved to Bydgoszcz.

In 1945, she passed her Matura exam, which is a high school leaving exam in Poland. She then studied Polish language and literature at the University of Łódź. In 1946, she took a course on literary criticism, learning how to analyze and review books. She started publishing her own articles and reviews in 1947.

In 1948, Maria Janion began working at the Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences. She stayed there until she retired in 1996. She also taught at the Higher Pedagogical School in Gdańsk starting in 1957. In 1968, she became the head of the 19th-Century Literature Department.

However, after the 1968 Polish political crisis, she was removed from her teaching role. The communist government was worried about her growing influence on students. Her lectures focused on the revolutionary and free-thinking parts of Romanticism. This was different from the official way literature was taught. She encouraged her students to think bravely and originally about Polish literature.

In the 1970s, Janion joined groups that secretly worked against communism in Poland. She helped start an independent Society of Study Courses. In 1973, she became a full professor of humanities. She also joined the Polish Writers' Union in 1979.

Maria Janion became more critical of the official ideas about Polish literature and history. She questioned traditional views on war, heroes, and sacrifice. In 1976, she wrote about a book that showed war from an ordinary person's view, not a heroic one. This caused a lot of criticism, as some accused her of disrespecting Polish values. Her independent ideas made her popular with students but also a target for the government.

When the Solidarity movement began, Maria Janion supported the workers' strikes. She asked for peaceful actions. In 1981, she spoke at a cultural congress, urging the national movement to focus on intellectual efforts. This was interrupted by martial law in Poland.

In the 1990s, she continued to be active in various organizations. She joined the Society for Humanism and Independent Ethics. She also became a member of the Polish Writers' Association and the Polish PEN Club. In 1994, she received another special honorary degree from the University of Gdańsk.

From 1997 to 2004, she was a judge for the Nike Award, Poland's most important literary prize. She even led the jury for some of those years. She continued to give public lectures at the Polish Academy of Sciences until 2010. Maria Janion passed away in Warsaw on August 23, 2020, at the age of 93.

Romanticism: A New Way of Thinking

Maria Janion believed that Romanticism was a major change in how people thought. It offered new ways to understand history, nature, and people. She pointed out that Romanticism increasingly focused on feelings of the absurd and the strange, often shown through irony and melancholy.

She thought Romanticism began with the discovery of the modern "self." This meant people started exploring their own unique experiences and mysteries. The Romantic imagination brought out a new reality: an inner world of dreams and phantasms (imaginary things). Janion introduced the idea of the "subconscious human," showing hidden thoughts and feelings.

This Romantic freedom came from rejecting classicism, which had very strict and narrow ideas about tradition. Classicism limited imagination. Romanticism, however, looked at tradition in many different ways. This new, open perspective became the basis for a new cultural way of thinking. Yet, in her book The Romantic Fever, she showed that Romanticism itself couldn't stay fixed. Even its followers ended up making its contradictions stronger.

In her books, Maria Janion explored many parts of this new way of thinking. She wrote about the new Romantic hero and how Romanticism broke the death taboo. She also looked at how hidden and forgotten things were rediscovered, like vernacular cultures (especially folk culture, but also pagan, Slavic, Nordic, and Oriental cultures). She discussed the idea of nature as a guide and how creation and destruction, or life and death, were linked. She also explored history as a divine event and the dramatic philosophy of existence, from salvation to nothingness. She even looked at experiences that were often ignored, like those of children, people with mental illness, or women.

Uncanny Slavdom

In her book Niesamowita Słowiańszczyzna (which means "Uncanny Slavdom"), Maria Janion used ideas from Edward Said's book Orientalism. She argued that in the Middle Ages, Western Slavs were influenced and changed by Roman Catholicism.

Janion believed that when Poles entered the world of Latin influence, they lost touch with their older pagan traditions. She felt this caused a kind of trauma that still affects their shared identity today. However, some scholars, like Dariusz Skórczewski, have disagreed with this idea. They believe she might have used postcolonial theory incorrectly and misunderstood the role of Christianity in Poland.

Personal Life

Maria Janion was open about being a lesbian. She shared this in a book called Janion. Transe – traumy – transgresje. She strongly supported feminism in Poland. She was also known for speaking out against racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, and misogyny (hatred of women).

Awards and Honors

Maria Janion received many awards for her important work:

- Życie Literackie Award (1972)

- Polish Academy of Sciences Secretary Award (1977, 1979)

- Jurzykowski Prize (1980)

- Honorary degree at the University of Gdańsk (1994)

- Great Culture Foundation Award (1999)

- Kazimierz Wyka Award (2001)

- Amicus Hominis et Veritatis Prize (2005)

- Golden Medal for Merit to Culture – Gloria Artis (2007)

- Paszport Polityki Award (2007)

- Finalist of the Nike Award for Niesamowita słowiańszczyzna (2007)

- Splendor Gedanensis Award (2007)

- Award of the Minister of Culture and National Heritage (2009)

- "Hiacynt" LGBT Award from the Equality Foundation (2009)

- Special Award of the Congress of Women (2010)

- Ordre national du Mérite, France (2012)

- Jan Parandowski PEN Club Prize (2018)

Published Works

Maria Janion wrote many books, mostly in Polish. Here are some of her important works:

- Lucjan Siemieński, poeta romantyczny (1955)

- Zygmunt Krasiński, debiut i dojrzałość (1962)

- Romantyzm. Studia o ideach i stylu (1969)

- Romantyzm, rewolucja, marksizm ("Romanticism, Revolution, Marxism") (1972)

- Humanistyka: Poznanie i terapia (1974)

- Gorączka romantyczna ("Romantic Fever") (1975)

- Romantyzm i historia ("Romanticism and History"), with Maria Żmigrodzka (1978)

- Odnawianie znaczeń ("The Refurbishment of Meanings") (1980)

- Czas formy otwartej (1984)

- Wobec zła ("In View of Evil") (1989)

- Życie pośmiertne Konrada Wallenroda ("The Posthumous Life of Konrad Wallenrod") (1990)

- Projekt krytyki fantazmatycznej ("The Project of Phantasmatic Criticism") (1991)

- Kuźnia natury (1994)

- Kobiety i duch inności ("Women and the Spirit of Dissidence") (1996)

- Czy będziesz wiedział, co przeżyłeś (1996)

- Płacz generała. Eseje o wojnie (1998)

- Odyseja wychowania. Goetheańska wizja człowieka w "Latach nauki i latach wędrówki Wilhelma Meistra", with Maria Żmigrodzka (1998)

- Do Europy - tak, ale razem z naszymi umarłymi ("To Europe : Yes, but Together with our Dead") (2000)

- Purpurowy płaszcz Mickiewicza. Studium z historii poezji i mentalności (2001)

- Żyjąc tracimy życie: niepokojące tematy egzystencji ("Living to Lose Life") (2001)

- Wampir: biografia symboliczna ("Vampire: A Symbolic Biography") (2002)

- Romantyzm i egzystencja ("Romanticism and Existence"), with Maria Żmigrodzka (2004)

- Niesamowita Słowiańszczyzna (2006)

Some of her works have been translated into English:

- Hero, Conspiracy, and Death: The Jewish Lectures, translated by Alex Shannon (2014)

- "Poland Between the West and the East", translated by Anna Warso (2014), in Teksty Drugie, 1, pp. 13-33.

Images for kids

See also