Marie-Antoine Carême facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Antonin Carême

|

|

|---|---|

Carême, by Charles de Steuben

|

|

| Born |

Marie-Antoine Carême

8 June 1783 or 1784 Paris

|

| Died | 12 January 1833 Paris

|

| Occupation | Chef and author |

Marie-Antoine Carême (8 June 1783 or 1784 – 12 January 1833), known as Antonin Carême, was a famous French chef. He lived in the early 1800s and is known as one of the first celebrity chefs.

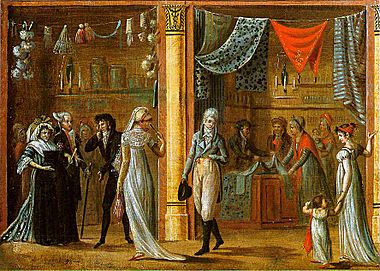

Carême was born in Paris into a family that didn't have much money. As a child, he started working in a simple restaurant. Later, he became an apprentice to a top Parisian pastry chef. He quickly became known for his amazing skills with pastries. He loved architecture and was famous for his large pièces montées. These were huge table decorations made from sugar, shaped like classical buildings.

Carême worked with other leading chefs of his time. He learned all parts of cooking. He became the head chef for important people. These included Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, Tsar Alexander I of Russia, and the Prince Regent in Britain. He helped create and simplify classic French cooking. He always used the best and most expensive ingredients. People thought he was the best chef of his time.

Carême wrote many books with beautiful pictures. He wanted to share his cooking skills with other chefs. These books taught how to make grande cuisine for rich and important people. His ideas stayed popular after he died. Chefs like Jules Gouffé and Auguste Escoffier continued his style.

Contents

Life and Career of a Chef

Early Years and Beginnings

Marie-Antoine Carême, known as Antonin Carême, was born in Paris. His exact birth date is not known for sure. Most people agree it was 8 June, either in 1783 or 1784. He was one of many children born to Marie-Jeanne Pascal and Jean-Gilbert Carême. His father was a construction worker. The family lived in a very simple home, like a shack, in a poor part of Paris.

The French Revolution started in 1789. This stopped a lot of building work in Paris. Carême's father found it hard to feed his family. So, Carême started working at a very young age. He worked at a gargote, which was a very basic and cheap restaurant.

There are different stories about how this happened. Carême himself said his father sent him away in 1792. His father told him to find a place that would take him in. One story says he found a humble cookshop. There, he got his first cooking lessons. Other people think his family simply arranged for him to work there.

Stories also differ about what happened next. Some say he stayed at the gargote for over five years. He swept, washed, ran errands, and served food. Later, he helped prepare meals. Another story says he left after a few months. He then worked for a baker named Père Ducrest. This baker was on the rue Saint-Honoré. People said Carême would hurry through the streets delivering baked goods. At night, he slept in Ducrest's kitchen. It is also said that Ducrest's children's tutor taught Carême to read and write.

Becoming a Pastry Apprentice

Carême's life is better known from 1798. This is when he started an apprenticeship at Sylvain Bailly's pastry shop. It was also a restaurant on the rue Vivienne. This was a big step up for his career. After the French Revolution, making pastries was the most respected cooking art. Bailly was one of the best pastry chefs. Important people like the French foreign minister, Talleyrand, were his customers.

Bailly's shop was near the busy Palais-Royal. One of Carême's first jobs was to go there. He would encourage visitors to come to his employer's restaurant. As a pastry apprentice, Carême started as a tourier. This meant he worked with dough. He would fold and roll it many times to make perfect puff pastry. He became very skilled at this. Later, he used this skill for two famous pastries: the vol-au-vent and the mille-feuille.

Bailly had a famous cake called gâteau de plomb. Carême suggested how to make it lighter. He also invented new decorations for it. He slowly became more responsible. Bailly let him have two afternoons off each week. Carême used this time to visit the old royal library. It was across the road from the restaurant. He read many books. He read cookbooks from different countries and times. He also read about his other big interest: architecture. He later wrote about his love for architecture. He said he couldn't become an architect because he didn't have enough money.

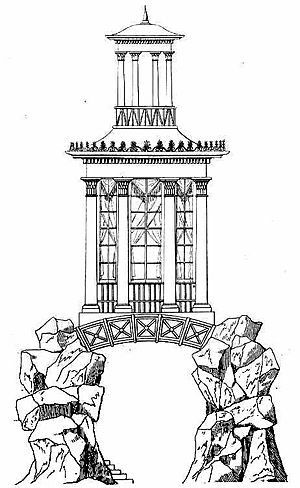

Bailly wanted new ideas to attract customers. He wanted amazing pièces montées in his windows. These were fancy pastry displays. Sculpting with sugar paste was popular before the revolution. But it had been forgotten. Carême helped bring this art back. He made croquembouches and grand showpieces. These were based on the ancient buildings he studied in the library. He is famous for saying, "The fine arts are five in number: music, painting, sculpture, poetry and architecture − of which the principal branch is confectionery". His creations had Greek columns, Chinese pagodas, and Egyptian pyramids. They got a lot of attention. Sometimes, he mixed different styles and eras in one pièce montée.

Moving Up in the Cooking World

After three years with Bailly, Carême joined another famous pastry chef, Gendron. Gendron's shop was on the rue des Petits-Champs. Carême liked working for Gendron. His skills were valued by important customers. These included the finance minister, the marquis de Barbé-Marbois. Gendron also let Carême work on his own for special events. Carême catered for important banquets.

In 1803, Carême opened his own shop on the rue de la Paix. He ran it for ten years. While running his shop, he also had a very successful career. He worked as a pastry chef and later as a head chef. He cooked for big imperial, social, and government parties. In October 1808, Carême married Henriette Sophy Mahy de Chitenay. They did not have children together.

Carême became skilled in all areas of cooking, not just pastries. He learned from earlier cooks and food writers. He studied books like Le cuisinier moderne (1736) and Soupers de la cour (1758). He worked with top Parisian chefs. He later wrote that he learned about sauces from the famous sauciers of the house of Condé. He learned about cold buffet cooking at the Hôtel de Ville. He learned about modern cooking and running a big kitchen at the Élysée Napoléon.

From 1803 to 1814, Carême worked as a pastry chef for Talleyrand. This was at the Hôtel de Galliffet. He continued to learn about all kinds of cooking. He was hired to cater for special events. These included the weddings of Jérôme Bonaparte to Catharina of Württemberg (1807) and Napoleon to Marie-Louise of Austria (1810). Carême was old enough to be called into the army. But he was not. Talleyrand might have helped him avoid it.

The Peak of His Career

After Napoleon lost in 1814, the British and Russians took over Paris. Talleyrand wanted to be friends with them. He invited Tsar Alexander I to stay with him. Talleyrand asked Carême to make sure the tsar had amazing meals every day. One writer, Marie-Pierre Rey, said that Talleyrand's good food helped the tsar feel positive towards France.

The tsar stayed with Talleyrand for some weeks. Then he moved to the Élysée Palace. He asked Carême to be his head chef there. This job put Carême at the very top of his profession. He was already a famous pastry chef. Now he was the head chef for the most powerful man in Europe. He showed his employer's importance with his grand cooking. The next year, after Napoleon's brief return and final defeat at Waterloo, Alexander came back to Paris. He again asked Carême to cook for him.

The tsar gathered his troops for a big review at Châlons-sur-Marne. Carême had to prepare three banquets for 300 people each. This was very hard because of the supplies. There was little food nearby. Food, wines, tablecloths, glasses, and even animals had to be brought from Paris. That was over 80 miles away. Carême also had to deal with the tsar's preference for Russian service. This meant serving one dish at a time. This was different from the French way. In French service, many dishes were put on the table at once. Carême thought French service was more elegant. But service à la russe slowly became popular across Europe.

In 1815, Carême published his first books. Le Pâtissier royal parisien was a two-volume book of recipes for skilled pastry chefs. Le Pâtissier pittoresque focused on piéces montées. It had over 100 of Carême's drawings of designs. It also had instructions on how to make them.

In 1816, Carême became the chef for the Prince Regent in London. He worked at Carlton House and the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. This was Carême's first time working outside France. He was paid a very high salary. The prince loved his food. But Carême was not happy. He hated the English weather, especially the fog. This made his breathing problems worse. He had these problems from working in smoky kitchens for years. He also found the prince's staff unfriendly. He later wrote that he was very bored and homesick. He went back to France in late 1817.

Travels to St Petersburg, Paris, and Vienna

Tsar Alexander returned to Paris in 1818. He was on his way to a meeting in Aix-la-Chapelle. Carême's friend Muller, who managed the tsar's household, convinced Alexander that having Carême cook would make his group look better. He asked Carême to cook for the tsar at Aix. Then he asked him to travel to Russia. Carême agreed to go to Aix. He got a good salary and a big budget. But he said no to going to Russia.

After working briefly in Austria and England for Lord Stewart, Carême decided to accept the tsar's offer. He traveled by sea to St Petersburg in mid-1819. The timing was not good for him. As he arrived, the tsar left for a long visit to Archangel. While the tsar was away, Carême explored St Petersburg. He found its buildings inspiring. He called it "the most beautiful city in the world". But by the time the tsar returned, Carême was not happy with Russia. He didn't like the food or the way things were run at the court. He left at the end of August.

When he returned to Paris, Carême became the head chef for Princess Catherine Bagration. She was a distant cousin of the tsar. She was also the widow of a famous general. Carême enjoyed working for the princess. She lived in style and loved good food. But she didn't entertain on a large scale because of her health. This meant Carême, a top chef, wasn't fully busy. Lord Stewart then asked Carême to work for him again.

While working for Stewart, Carême introduced something that became a symbol for chefs: the toque hat. Before this, chefs usually wore loose caps. Carême thought these caps looked like something for sick people. He felt a chef should look healthy. The toque hat quickly became popular with chefs in Vienna, Paris, and other places.

Carême kept writing books. In 1821, he published two books about architecture. Projets d'architecture dédiés a Alexandre 1 had drawings of his ideas for new buildings in St Petersburg. The second book, Projets d'architecture pour l'embellisement de Paris, did the same for Paris. The next year, he wrote about catering in Le maître d'hotel français. He compared old and new cooking styles. He also showed seasonal menus he had made in Paris, St Petersburg, London, and Vienna. The title showed Carême's strong belief. He thought the head chef should control not only the cooking but also how the food was served.

Final Years of a Master Chef

Carême's last paid job started in 1823. He became the chef for the banker James Rothschild and his wife Betty. Rothschild was the richest man in France. Carême was happy to work for a rich employer, just like royalty. The Rothschilds paid Carême a lot of money. They also gave him plenty of time off to write his books. He published Le Cuisinier parisien in 1828. With Carême in charge of the food, the Rothschilds' home became a center for Paris high society. Carême's name was often in the newspapers.

By the late 1820s, Carême's health was getting worse. The Rothschilds offered him land to retire on their country estate. But he wanted to stay in Paris. He said no to a final offer from the former Prince Regent, now George IV, to come back to England. He retired to his house in Paris, near the Tuileries.

In retirement, Carême worked on his last big project. It was called L'Art de la cuisine française au XIX siécle. It was meant to be a five-volume work with many pictures. He finished the first three volumes. His student, Armand Plumerey, added the last two volumes that Carême had planned.

Carême died at his Paris home on 12 January 1833. He was 48 or 49 years old. He was mentally sharp until the end. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery.

Carême's Impact and Legacy

Carême was known as "the king of chefs and the chef of kings". He is still the most famous French chef of the 1800s. Some people see him as a great genius of haute cuisine. They see him as an example of how a poor apprentice could become a top chef. Others think he was too proud. They found his writing not elegant. They also thought his menus were "pretentious and heavy". They saw his piéces montées as a waste of food. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle.

Carême is famous for organizing the main sauces. These are called the mother sauces, or grandes sauces. They are the base for classic French haute cuisine. His recipes for Velouté, Béchamel, Allemande, and Espagnole became standard for French chefs. Later chefs, like Auguste Escoffier, kept his ideas. The idea of mother sauces is still used by cooks today.

Carême's cooking was for the very rich and important people. He advised people with less money not to try his fancy cooking. He said it was "Better to serve a simple meal, well-prepared". He didn't like some old cooking habits. For example, putting fish with meat. He also invented or improved several French cooking items. These include choux pastry, vol-au-vents, profiteroles, and mille-feuilles.

Carême's influence lasted after his death. His style was continued by chefs like Jules Gouffé and Urbain Dubois. It was made strong again by Escoffier. This style of cooking continued until nouvelle cuisine and simpler styles became popular in the late 1900s.

Books by Carême

| Year | Title | What it's about | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1815 | Le Pâtissier royal parisien | A guide to old and new pastry making, with notes on improving the art. It also reviews big parties from 1810 and 1811. | Dentu, Paris |

| 1815 | Le Pâtissier pittoresque | Focuses on piéces montées (fancy sugar sculptures). It starts with a section on the five orders of architecture. | Didot, Paris |

| 1821 | Projets d'architecture, dédiés à Alexandre 1er, empereur de toutes les Russies | Architectural designs for new buildings in St Petersburg. | Didot, Paris |

| 1821 | Projets d'architecture pour l'embellissement de Paris | Architectural designs for making Paris more beautiful. | Didot, Paris |

| 1822 | Le Maître d'hôtel français | Compares old and modern cooking. It details seasonal menus used in Paris, St Petersburg, London, and Vienna. | Didot, Paris |

| 1828 | Le Cuisinier parisien | About the art of French cooking in the 19th century. | Didot, Paris |

| 1833–1847 | L'art de la cuisine française au dix-neuvième siècle | The art of French cooking in the 19th century. Volumes 1–3 by Carême; Volumes 4–5 by his student Plumerey. | Dentu, Paris |

|

See also

In Spanish: Marie-Antoine Carême para niños

In Spanish: Marie-Antoine Carême para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |