Mary H. J. Henderson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary H J Henderson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1874 |

| Died | 6 November 1938 |

| Occupation | administrator with the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service |

| Known for | support for SWH and War Relief, social causes, including women's suffrage |

| Awards | Five medals |

Mary H J Henderson (born 1874 – 6 November 1938) was a brave woman who helped lead the Elsie Inglis's Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service during World War I. She worked in the Balkans and earned five medals for her service. Mary also started many groups led by women in Dundee, Aberdeen, and London. These groups helped with social issues, war relief, and getting women the right to vote. She was also a war poet, writing about her experiences.

Contents

Mary Henderson's Life Story

Mary Helen Jane Henderson was born in Old Machar in 1874. Her father, William Low Henderson, was an architect in Aberdeen. She had a twin brother and was related to Lady Dunedin. As a child, Mary lived near Queen Victoria's Balmoral Castle. She often played there with the royal grandchildren. Later, she wrote about meeting Queen Victoria, who gave her a photo in 1887. Mary also wrote about John Brown, the Queen's Scottish servant. She had also lived in Italy for several years.

Mary lived most of her life in Broughty Ferry, Dundee. She was a leader in many groups that helped women get the right to vote, supported war efforts, or worked to stop alcohol use. She also cared for women and children. Mary raised money for the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service. Later, she joined them as an administrator for a unit in Serbia. After the war, she shared her experiences through talks and poetry. She continued to create groups for women to be active citizens.

Mary died in 1938 after a car accident.

Helping Her Community

In 1913, Mary suggested that a woman should join the board of the Dundee Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Her idea was accepted. She also helped start the Dundee Infant Hospital. However, she was upset when women doctors were fired from the hospital in 1919. She felt it was unfair, as women had helped create the hospital. But after the war, men were often preferred for jobs, including in medicine.

Mary was one of three women who ran in the 1914 Dundee School Board elections. The newspapers showed her picture and mentioned her role in the women's suffrage society. Another woman who supported women's voting rights, Agnes Husband, won a seat. Mary got many votes but was not elected because of the voting system at the time.

Mary led the Dundee Women's Suffrage Society starting in 1913. She also joined the Dundee Women's War Relief Executive Committee in 1914. She became the secretary for the Scottish Women's Hospital for Foreign Service (SWH). In 1916, Dr. Elsie Inglis asked her to be the administrator for a new SWH unit. This unit would work with the Serbian Army in the war zone. Before leaving, Mary organized events for women and children whose husbands were away. She also arranged protests for temperance (asking to ban alcohol during the war). She even helped recruit more men to join the army. Mary also started a women's debating group called the Steeple Club. Later, she helped form the London Women's Forum. She was even presented to the King and Queen at Buckingham Palace for her war service. The King shared his sadness about the death of Dr. Elsie Inglis with her.

Working for Women's Right to Vote

In 1913, Mary was the honorary secretary of the Dundee Women's Suffrage Society. This group was peaceful and not linked to any political party. They gained 40 new members that year, reaching a total of 205. Mary believed that more public support would eventually help women get the right to vote. She felt that the national group, the NUWSS, needed to focus on educating political parties.

That year, Mary hosted a cafe chantant (a type of musical show). Suffragist Alice Crompton spoke there, explaining that the peaceful movement had grown to 60 branches and almost 40,000 members across Scotland. Lady Baxter also gave a supportive speech. In January 1914, Mary led a meeting between the Dundee NUWSS and the Independent Labour Party. She became the Parliamentary Secretary of the Scottish Women's Suffrage Societies. A speaker named Ethel Snowden captivated a large audience.

When World War I began, the more aggressive campaign for women's voting rights stopped. Mary wrote to the Lord Provost of Dundee. She offered the Dundee Women's Suffrage Society's members, buildings, and resources to help with war relief. She wanted to avoid mistakes that happened during the Boer War. They agreed to form the Dundee Women's War Relief Executive Committee (DWWREC), and Mary became its first secretary. In August 1916, she told the Dundee WSS that their branch had raised the most money for the Scottish Women's Hospitals out of any suffrage group in the UK. By March 1918, they had raised £3,641.

In 1916, Mary thought that people were ready to give women the vote. But she wondered if this feeling would last once it became a real political issue after the war.

Leading War Relief Efforts

As the first secretary of the Dundee Women's War Relief Executive Committee (DWWREC), Mary made sure each city area had its own local committee. She led a project to help women find jobs, including starting a toy factory that paid female workers. Her group also gave money to unemployed women. The Prince of Wales Fund Executive, led by the Lord Provost, made Mary's volunteer group an official committee. This happened after Mary Paterson, secretary of the Scottish Committee on Women's Employment, praised their work.

The paid work for women was seen as a start for a real industry that could employ unemployed girls. It offered training in typing and dressmaking, and the toys made were sold. Mary's volunteers collected and gave out comfort items to soldiers and sailors. They also organized clubs for local troops and social evenings for women. The popular newspaper The People's Journal reported that the women of Dundee had given many items to the Black Watch, RNVR, and other groups. Donations to the DWWRC grew throughout the war.

The Courier newspaper reported in October 1914 that Mary had announced 15,834 pairs of socks, over 200 shirts, and other items like cholera belts, mitts, cuffs, mufflers, and helmets had been sent to the front. She regularly updated the DWWREC on the total donations. By November 1916, over 148,000 items had been sent to comfort the troops.

Before Christmas 1914, Mary said that 36,000 items were being donated each month. They received thank-you letters from the front. The toys sold had raised £50. The Edinburgh Women's Emergency Corps even visited to learn how to make toys.

Her committee had another new idea for Primrose Day. They charged people to have a "charming girl" pin a "beautiful blossom" on their clothes. The money raised helped buy shirts, socks, and other comforts for soldiers. Mary also explained that some cash went to the Dundee and Tayport Red Cross. The group was also thinking about opening a "dry" (non-alcoholic) canteen.

Supporting Temperance During Wartime

Mary Henderson was a main speaker after thousands of women marched through Dundee. They were promoting temperance, asking for a ban on alcohol during the war. She said this would be a "patriotic act." Lady Baxter, the Salvation Army, Girl Guides, and other temperance groups led the parade with banners. They asked people to give up alcohol during the war. Mary, who didn't usually avoid alcohol herself, said she was convinced it was "best for the country" to ban alcohol sales and production during the war and for a time after. Mr. Mackay from Glasgow said that Dundee women had the right to ask for this. He said they had given their sons for freedom and had the right to ask the country to protect their sons in return.

Helping Families and Recruiting Soldiers

Mary was very interested in the well-being of mothers and children. She helped organize a social event for families at the Blackscroft Clinic in Dundee. Prizes were given for regular attendance and for taking good care of "delicate" children. She thanked the hosts and praised the mothers for their "true patriotism" in raising strong, healthy, and happy children.

In 1915, she led a musical show for Dundee troops at the opening of the Overgate soldiers' and sailors' canteen. She also joined the wives and daughters of troops at a new recruiting event. Two thousand women marched with flags and banners, encouraging young men to join the army, just like their own husbands and fathers had done.

Working with Scottish Women's Hospitals

In June 1915, Mary became the honorary secretary of the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service (SWH). She worked hard to raise money in many places. She encouraged groups to raise funds or to pay for specific hospital beds, like the "Broughty Ferry St. Margaret's School Bed" or the "Montrose Girls Club Bed" at SWH Royaumont in France.

After visiting SWH units in France, Mary gave talks with slides. She also hosted entertainment for the wives and children of soldiers. A large audience heard Mary explain why these "brave women" were treating Allied soldiers and not their own wounded. This was because the British Army and Red Cross had told Dr. Elsie Inglis that women were not needed. However, the women's hospital services were welcomed by the Belgian, French, and Serbian Allies. Mary reported that SWH had grown to 250 staff members and could care for 1,000 patients. She mentioned that French General Joffre had given 300 of 1,000 francs meant for French hospitals to the SWH. People from Dundee had raised £1,500. Some local people working at SWH included Dundee university graduates like Dr. Laura Sandeman, Dr. Lena Campbell in Serbia, and Dr. Keith Proctor in France. Miss Shepherd and the daughter of ex-Provost Lindsay from Broughty Ferry were also there.

Later that year, Mary spoke in Brechin and at the local suffrage society in Cupar. This group sponsored a "Cupar-Fife" bed in SWH Serbia. Dr. Inglis herself was a Scottish supporter of women's voting rights. In March 1916, Mary presented the "grand mission" of SWH at a well-attended fundraising concert. She also led an event where Dr. Alice Hutchison spoke about SWH in Serbia, filling in for Dr. Inglis in April 1916.

News of Mary leaving to join Dr. Inglis herself "disturbed" the DWWREC, as they would miss her hard work. But the public and national suffrage groups recognized that her skills would greatly help Dr. Inglis's unit. Before she left, Mary had founded the Dundee women's civic group, the Steeple Club. In August 2016, the Dundee Women's War Relief Executive Committee gave Mary gifts like an attaché case, a tartan blanket, pens, and paper, as well as flowers. She thanked them for praising her relief work, saying it was thanks to a good team.

Administrator in Serbia

Mary then worked as an administrator in Serbia and Russia with a new unit of Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service. She organized and worked in very dangerous conditions during the difficult retreat of the Serbians. She worked alongside Evelina Haverfield, who was the unit commandant. The unit sailed from Liverpool on August 30, 1916. Mary sent a postcard saying "all well" on October 21, 1916. In November 1916, Mary sent another postcard from Odessa.

A month later, she was home for a short break. In an interview with The Scotsman, she explained that 75 Scottish, English, and Irish women made up the hospital unit and the transport unit (ambulance drivers). She spoke of their calmness and cheerfulness despite the dangers and hardships, saying "the girls were splendid."

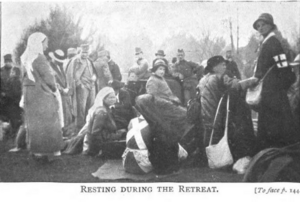

Mary described how quickly they set up a hospital. They were able to receive 100 patients less than a day after arriving. A week later, they moved to a field hospital (tents) closer to the front at Boulboulmink. But when the fighting got too close, the group moved again. They mixed with retreating Serbian and Rumanian troops and farmers with their animals. They traveled through snow, mud, and darkness, with bombs falling less than a mile away.

More details about Mary and SWH's difficult journey, their fear of being captured, and her responsibility for the women under her care were shared in Common Cause, a suffrage newspaper. This was the next part of her war stories.

Mary had left the main group with a small team to find Dr. Chesney's unit. But the women got separated from the Serbian forces. They slept outdoors before reaching "civilization" with the Russian authorities in Reni. Then they traveled by train with Dr. Inglis's group. Mary said the train was very crowded. She saw a Russian doctor stop a soldier with cholera from getting on the train. She called this the most "pathetic" thing she had seen, "that poor man put off the train and left in the darkness." The train was also almost bombed by enemy planes, but the quick-thinking driver saved them. They faced challenges crossing enemy-occupied land. Mary noted that even though the group was in great danger, very little equipment was lost. The next tent hospital at Boulboulja was exposed to enemy aircraft because it was on a wide, flat plain. Again, the women in the transport teams worked immediately after arriving to bring in the wounded for urgent care, even though they were very tired.

Mary's stories about the Serbian (Rumanian) retreat were featured in The People's Journal. She said that in their grey khaki uniforms and military manner, it was "almost impossible" for local farmers to tell their gender at first glance. She said Serbians and Rumanians "knew" the people from the Scottish Women's Hospital as "angels in disguise."

The Telegraph and The Guardian reported her return to London in 1917. They wrote about her experiences in Dobrudja and her struggles during the Serbian retreat. They mentioned she was in Constanza, a city full of wounded soldiers, and had left just one day before the Germans took over the city. Also, in Bucharest, hospitals were being emptied. The nurses were dealing with 1,000 to 3,000 injured people each day. Mary believed this showed the "success of the British Military Mission" in that area. She returned home to organize supplies after the retreat, traveling through Norway. In November 1917, Mary gave another lecture in Dundee. She "held the attention of a large audience" with her powerful descriptions and images of the hospitals' work. She stressed how important the allies in Belgium, Serbia, and Rumania were to the overall war effort. She said that out of 60,000 boys (over 11 years old) who left during the Serbian retreat, only 15,000 survived. 45,000 had died on the road or later from being exposed to the cold. She then spoke in Manchester in July 1917, to help raise money for the Rumanian Red Cross.

Writing About the War

Mary Henderson wrote about her experiences, just like some other women in the SWH. She kept war diaries and wrote poetry.

Her poems were described as showing "a vision of war seen from the inside" through a woman's mind. She called the nurses "her sisters." One critic said her poem The Cargo Boat, which described the everyday efforts of bringing supplies, was "worthy of Kipling at his best." In another poem, The Incident, she compared an injured soldier to Christ and his nurse to a mother. She wrote about a similar idea in A Young Serbian.

In another poem, she dedicated it "to the rank and file of the Elsie Inglis Unit." It was called Like That, based on a quote from the Prefect of Constanza: "No wonder Britain is so great if her women are like that." In this poem, written in November 1916, Mary wrote that the war nurses were as heroic as the men fighting:

I've seen you kneeling on the wooden floor,

Tending your wounded on their straw-strewn bed,

Heedless the while, that right above your head

The Bird of Menace scattered death around.

...

I've seen you, oh my nurses, 'under fire',

While in your hearts their burned but one desire -

What British men and women hold so dear -

To do your duty without any fear.

In Russia After the Revolution

Mary Henderson was in Petrograd on March 18, 1917, just days after the February Russian Revolution. She told a reporter from Dundee Courier that she was impressed by the "wonderful order" in the streets. Volunteers, all armed, kept the peace. She reported joyful singing of the Russian revolutionary song, the Marseillaise. She was also surprised to see "cartoons and caricatures of Emperor, the Empress and Rasputin" openly for sale. She shared her political opinion that "the strength of Russia" was in M. Kerensky, their Minister of War. She felt that the huge size of the country made it hard for the new government to form alliances. But she was sure that "the women do not fail" in understanding patriotism in its broadest sense.

After the War: Women Citizens Association

In 1918, the Representation of the People's Act gave some women the right to vote. This included women over 30 or those who owned certain property. Mary Henderson was one of the speakers at the first meeting of a branch of the Women Citizens Association in April 1918. Every seat was taken, and women from all backgrounds were there. Mary was elected to the committee. The group's goal was not just to involve "new voters" but to represent and encourage discussions among all women.

Mary said that "one of women's supreme privileges was the preservation of the race." In a later discussion with the Dundee Council about housing, she asked a very important question: What part of wages should be paid as rent? The councillors could not answer. This led Mary to ask the Women Citizens Association to research how much rent people were currently paying compared to their income. She also urged the city to create a permanent women's center instead of using temporary places. She argued that this would greatly increase the power of the city's women.

Starting Other Women's Groups

The Steeple Club, which Mary had formed before her SWH service, met on November 23, 1917. Mary shared her belief that "like-minded" women were "city mothers," just like there were "city fathers." She felt the group had proven its worth. She believed that "civic consciousness" or a sense of community was simply women's natural instinct to make a home, but expanded to include the home life of the city and the country. In its second year, the Steeple Club was a success. It held 58 meetings or events and an exhibition of women artists' work to raise money for the Dundee Prisoners of War Fund. In its third year, it held over 100 events. Mary was re-elected as president, even though she moved to London for a while. The newspapers reported that the Steeple Club had grown in its "sense of civic consciousness."

Mary Henderson was one of the founders of the Ladies' Forum Club in London. This club was owned and controlled by women. She served on the first committee with another Scottish woman, Janie Russell. It was noted that Mary "was well known and esteemed for her public service." She had served in Serbia and Russia at the Scottish Women's Hospitals and had crossed the North Sea four times in one year. Her poem Judith and Holofernes was considered a serious poem and praised by critics. She attended the opening event in uniform with Florence Haig, a suffragette activist.

In 1925, Mary was back in Scotland. She started and became the managing director of the Ladies' Town and County Club in Aberdeen. Now living in Lumsden, she became involved with the local hospital, the District Nursing Association, and the local Women's Rural Institute (W.R.I.). She was also a member of the Soroptomist Club.

Her Death

Mary Henderson was 64 years old when she died on November 6, 1938, at the Nicoll Hospital in Rhynie. She had served on the hospital's executive board. She had been seriously injured the day before in a car accident.

This accident happened in Strathdon as she was traveling home from Ballater. A passing driver found her lying injured near her overturned car. She was conscious at first and said "something went wrong."

When she died, her twin brother was living in Wales. Her nephew, Alexander Whyte Henderson, was a pall-bearer at her funeral in Clova chapel. A special church service was held before the funeral. Mary Henderson's five war medals were displayed at her funeral. Many local people attended, including representatives from groups she had helped, such as the WRI, the District Nursing Association, and the hospital.

She is buried in Auchindoir Churchyard. One of her poems, My Desire, says:

'Oh lay me where the morning mist

Lies softly on the hill,

Where the light and shade of summer cloud

Flits to and fro at will.'

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |