Massacre of Glencoe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Massacre of Glencoe |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Jacobite rising of 1689 | |||||

After the Massacre of Glencoe, Peter Graham |

|||||

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

| Clan MacDonald of Glencoe | |||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

Alasdair MacIain | ||||

| Strength | |||||

| 920 | Unknown | ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| None | About 30 killed | ||||

The Massacre of Glencoe (Scottish Gaelic: Murt Ghlinne Comhann) happened in Glen Coe in the Highlands of Scotland on 13 February 1692. About 30 members of the Clan MacDonald of Glencoe were killed by Scottish government soldiers. This happened because they were accused of not swearing loyalty to the new rulers, William III and Mary II.

By May 1690, a conflict called the Jacobite rising of 1689 was mostly over. But there was still unrest in the Highlands. This used up military resources that were needed for a bigger war in Flanders. In late 1690, the Scottish government offered Jacobite clans £12,000. This money was for them to promise loyalty to William and Mary. However, the clan chiefs argued over how to share the money. So, by December 1691, none of them had taken the oath.

The government wanted the deal to happen. Lord Stair, a high-ranking official, decided to make an example. This would warn others about what would happen if they delayed. The Glencoe MacDonalds were not the only ones who missed the deadline. The Keppoch MacDonalds also swore their oath in early February. The exact reasons why the Glencoe MacDonalds were chosen are still debated. It seems to be a mix of clan politics and their reputation for not following laws.

Such violent events were rare by 1692, so the massacre shocked people. It became a key reason why Jacobitism (support for the old kings) continued in the Highlands. It remains a powerful symbol even today.

Contents

Why the Glencoe Massacre Happened

Some historians believe the Scottish Highlands were more peaceful in the late 1600s than often thought. Clan chiefs could be fined for crimes their clansmen committed. But the area called Lochaber was an exception. Government officials and other chiefs saw it as a place for cattle thieves. Four clans in Lochaber were often named: the Glencoe and Keppoch MacDonalds, the MacGregors, and the Camerons.

These clans had been involved in conflicts before. They took part in a raid after Argyll's Rising in 1685. This raid caused problems in the central and southern Highlands. The government had to use soldiers to bring back order. Before James VII and II was removed from power in 1688, he declared the Keppoch MacDonalds outlaws. This was for attacking his troops.

When James tried to regain his kingdoms in 1689, some Highland clans joined him. This was part of a campaign in Scotland. The main Jacobite resistance ended in May 1690. But much of the Highlands was still not under government control. Policing this area used up soldiers needed for the Nine Years' War in Flanders. Also, unrest in Western Scotland often spread to Ulster in Ireland. So, controlling Lochaber was important for peace in both countries.

The Oath of Loyalty

After a battle called Killiecrankie, the Scottish government tried to make peace with the Jacobite chiefs. In March 1690, Lord Stair offered them £12,000. This was if they swore an Oath of allegiance to King William. The chiefs agreed in June 1691 at Achallader. The Earl of Breadalbane signed for the government. But the agreement did not say how the money would be divided. This caused arguments and delayed the oath. Breadalbane also wanted some money for damage done to his lands by the Glencoe MacDonalds.

A battle in Ireland in July 1691 ended the Jacobites' chances of winning there. On 26 August, the Scottish government announced a Royal Proclamation. It offered a pardon to anyone who took the oath before 1 January 1692. Those who did not would face severe punishment. Secret documents then appeared, saying the Achallader agreement would be cancelled if the Jacobites invaded. Lord Stair believed none of the chiefs planned to keep their word.

In early October, the chiefs asked James, the former king, for permission to swear the oath. They knew he could not invade before the deadline. James sent his approval from France on 12 December. Glengarry, a MacDonald chief, received it on 23 December. But he did not share it with other chiefs until 28 December. The reason for this delay is unclear. It might have been a power struggle within the MacDonald clan.

Because of this delay, MacIain of Glencoe did not leave to take the oath until 30 December. He went to Fort William to see its governor, Lieutenant Colonel John Hill. Hill was not allowed to accept the oath. So, he sent MacIain to Inverary with a letter for Sir Colin Campbell, the local judge. MacIain took the oath on 6 January, after the deadline.

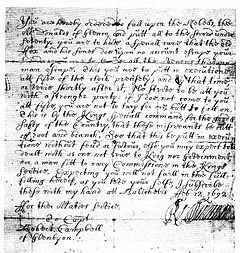

Even though Glengarry also swore late, only MacIain was excluded from the pardon. Lord Stair's letters show he decided to make an example before the deadline. He first planned a bigger operation to destroy several clans. But by 11 January, he focused on Glencoe. He wrote, "my lord Argile tells me Glenco hath not taken the oaths at which I rejoice...." This suggests the Glencoe MacDonalds became the target around this time.

The decision to target the Glencoe MacDonalds had many reasons. Stair was under pressure to make the peace deal work. Argyll, another powerful figure, was competing for influence. Glengarry was later pardoned and got his lands back. He also helped Jacobite officers escape to France.

What Happened During the Massacre

In late January 1692, about 120 soldiers from the Earl of Argyll's Regiment of Foot arrived in Glencoe. Their commander was Robert Campbell of Glenlyon. He was a local landowner whose niece was married to one of MacIain's sons. Campbell's orders were for "free quarter." This meant the soldiers would stay in the homes of the Glencoe MacDonalds without paying. This was a common practice at the time. The Glencoe MacDonalds had also done this to the Campbells in the past.

Most of the soldiers in the regiment came from areas damaged by earlier raids. On 12 February, Colonel Hill ordered Lieutenant Colonel James Hamilton to take 400 men. They were to block the northern exits from Glencoe. Meanwhile, another 400 men under Major Duncanson would join Glenlyon's group. They would sweep through the glen, killing people, taking property, and burning houses.

On the evening of 12 February, Glenlyon received his orders from Duncanson. The orders were very strict. They warned him to carry out the plan without mercy. Captain Thomas Drummond, a senior officer, delivered the orders. His presence was to make sure Glenlyon followed them. Witnesses later said Drummond shot two people who asked Glenlyon for mercy.

Lord Stair's letters show he wanted the plan kept secret. He feared the MacDonalds would escape if warned. A soldier named James Campbell said they did not know about the plan until the morning of 13 February. MacIain was killed, but his two sons escaped. The number of people killed varies in different accounts. Hamilton's men, who were far away, said 38 died. The MacDonalds themselves claimed about 25 were killed. Modern research estimates around 30 deaths. Claims that others died from exposure cannot be proven.

Major Duncanson arrived late, at 7:00 am. He joined Glenlyon after most of the killings had happened. Then, they moved through the glen, burning houses and taking livestock. Hamilton's men did not reach their position until 11:00 am. Two of his lieutenants were said to have broken their swords rather than follow orders. But this is unlikely, as they arrived hours after the killings.

After the massacre, the Argyll regiment was sent to England and then to Flanders. They served there until 1697. No one involved was punished. Glenlyon died of disease in 1696. Duncanson was killed in Spain in 1705. Drummond survived and took part in another Scottish disaster, the Darien scheme.

The Investigation and Aftermath

On 12 April 1692, a newspaper in Paris published a copy of Glenlyon's orders. This caused a lot of criticism of the government. But many people still thought the MacDonalds deserved punishment. The main reason for investigating the massacre was political. Lord Stair was not popular with either side of the government.

Colonel Hill claimed most Highlanders were peaceful. He said lawlessness was encouraged by leaders like Glengarry. He also said ordinary people never benefited from it. A commission in 1693 tried to use law to solve problems like cattle theft. But clan chiefs undermined this, as it reduced their control over their people.

The issue seemed settled until May 1695. Then, many political pamphlets were published in London. One of these was by a Jacobite writer, Charles Leslie. It focused on King William's alleged involvement in other deaths, with Glencoe as a secondary charge.

A new commission was set up to investigate. They looked into whether the massacre broke a 1587 law called "Slaughter under trust." This law was for murders committed in "cold blood." For example, when peace had been agreed, or hospitality accepted. The commission did not question if the orders were legal. Instead, they looked at whether the soldiers had gone beyond their orders. They concluded that Stair and Hamilton had a case to answer. But they left the final decision to King William.

Stair was removed from his job as Secretary of State. However, he returned to government in 1700. He was later made an earl by Queen Anne. The survivors of the massacre asked for money, but their request was ignored. They rebuilt their homes. They also took part in later Jacobite uprisings in 1715 and 1745. A recent study in 2019 showed Glencoe was lived in until the Highland Clearances in the mid-1700s.

Glencoe Today

The brutality of the Glencoe Massacre shocked Scottish society. It became a symbol for Jacobites of how badly they were treated after 1688. In 1745, Prince Charles had Leslie's pamphlet reprinted. The massacre then largely faded from public memory until 1850. At that time, a historian named Thomas Macaulay wrote about it. He tried to clear King William's name. He also suggested the massacre was part of a feud between the MacDonalds and Clan Campbell.

During the Victorian era, Scotland developed a strong sense of Scottish identity. Glencoe became part of a focus on the emotional side of Scottish history. This included things like "bonnie Scotland," the Jacobites, and tartan.

After Scottish history became a proper subject to study in the 1950s, Leslie's ideas still influenced views. William's reign was seen as bad for Scotland. The massacre was just one of several bad events. Others included the Darien scheme and the Union of 1707.

The massacre is still remembered today. The Clan Donald Society holds an annual ceremony. This started in 1930. It takes place at the Upper Carnoch memorial. This is a Celtic cross put up in 1883. Another memorial is the Henderson Stone. This granite boulder was once called the "Soldier's Stone." In the late 1800s, it was renamed "Henry's Stone." This was after a man believed to be MacIain's piper.

Recent Archaeological Discoveries

After the massacre, the Glencoe MacDonalds rebuilt their homes. A military survey from 1747 to 1755 shows seven settlements in the glen. Each had between six and eleven buildings. In 2018, archaeologists from the National Trust for Scotland began studying areas related to the massacre. They plan to publish detailed findings.

In the summer of 2019, they focused on a settlement called Achadh Triachatain, or Achtriachtan. This was at the far end of the glen. About 50 people lived there. Digs show it was rebuilt after 1692 and still lived in during the mid-1700s. So far, no items directly from the massacre have been found.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |