Matilda Coxe Stevenson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Matilda Coxe Stevenson

|

|

|---|---|

circa 1870

|

|

| Born |

Matilda Coxe Evans

May 12, 1849 |

| Died | June 24, 1915 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Miss Annable's Academy; private study of law with her father, Alexander H. Evans; of chemistry and geology with Dr. N. M. Mew of the Army Medical School, Washington, D.C.; of ethnology with her husband, James Stevenson, of the USGS |

| Spouse(s) | James D. Stevenson (m. 1872) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Ethnologist |

| Institutions | Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution |

Matilda Coxe Stevenson (born Evans) (May 12, 1849 – June 24, 1915) was an important American ethnologist, explorer, and activist. She also wrote under the name Tilly E. Stevenson. Matilda supported women in science and helped start the Women's Anthropological Society in Washington D.C.

She was the first woman hired by the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE). Her job was to research Indigenous people in the American Southwest. She wrote many books and articles about the Zuni people. Matilda faced challenges as a woman scientist in her time. She was very determined and worked hard to achieve her goals.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Matilda Coxe Evans was born in San Augustine, Texas, on May 12, 1849. She was the third of four children. Her parents, Maria Matilda Coxe Evans and Alexander Hamilton Evans, moved a lot. They lived in Texas, Washington D.C., and Pennsylvania.

Matilda's education was special for a girl back then. Most girls were taught to be wives and mothers. But Matilda also studied science, math, history, and geography. She went to Miss Anabel's English, French, and German School in Philadelphia. When she returned to Washington, she continued learning from her father, who was a lawyer. She also studied chemistry with William M. Mew, a chemist at the Army Medical Museum. Most colleges were only for men at that time. Matilda wanted to be a mineralogist, someone who studies minerals. But her plans changed when she met James Stevenson. He was a geologist and ethnologist.

Starting Her Career

Matilda married James Stevenson on April 18, 1872. Soon after, James left for an expedition to study geology in several states. Matilda's marriage made her more brave and eager for adventure. James always supported her work as a scientist.

In 1878, Matilda learned about ethnographic studies. This is a way to study cultures and people. She and James studied the Ute and Arapaho people. Matilda mostly taught herself how to do this research.

In 1879, the U.S. government created the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE). Matilda Stevenson became a "volunteer assistant in ethnology." The BAE believed that Native American cultures were disappearing. They wanted scientists to study and record these cultures. Matilda shared this view throughout her career. She went with James on his BAE trips to the Southwest. She was his official assistant but did not get paid for this work.

Matilda spent 13 years exploring the Rocky Mountains with her husband. In the 1880s, the Stevensons became the first husband-wife team in anthropology. During these trips, Matilda met the Zuni people. She would write most of her work about them. Matilda often focused on women and family life in her studies. She became known as a "vigorous and devoted scientist."

She also studied Zuni children and their traditions. For example, her essay The Religious Life of the Zuni Child looked at a boy's initiation ceremony. Her work on women and children was seen as suitable for a woman at the time. This allowed her to study many different topics beyond just family life.

During this time, Matilda became a skilled ethnographer. She was very good at collecting information. She did not rely on just one source, which was common at the BAE. She and her colleagues wanted to save Zuni and other Indigenous cultures. However, by visiting and interacting with the Zuni, they also changed their world. They spoke English, encouraged buying manufactured goods, and provided access to government schools. These actions, even if well-intended, altered Zuni life. Matilda believed that white people, especially women, had a duty to "civilize" Indigenous peoples.

Matilda became known for being very direct and determined. She would push to enter sacred ceremonies or spaces to get information. This approach was common among male ethnologists at the time. The BAE wanted to "save" Indigenous cultures, which led to such attitudes. Over the years, the Stevensons, Frank Cushing, and Stewart Culin collected many items from the Zuni. These included ceremonial objects, pottery, and clothes.

In 1881, Matilda met We'wha, a lhamana from the Zuni. We'wha became Matilda's lifelong friend. We'wha helped Matilda connect with the Zuni people until We'wha's death.

In 1885, Stevenson helped create the Women's Anthropological Society of America (WASA) in Washington D.C. She was elected its first President. Many WASA members were wives of politicians at first. Later, important women scientists like Anita Newcomb McGee and Maria Mitchell joined. WASA was important because women were often not allowed in men's professional groups. Being part of WASA helped these women feel like serious scholars.

Matilda invited We'wha to visit Washington. We'wha's visit helped Matilda get funding for future trips. It also made the Stevensons more important in Washington. In June 1886, Matilda and We'wha met President Cleveland and his wife. President Cleveland even talked with Matilda about how important ethnology was.

Later Professional Work

James Stevenson passed away on July 25, 1888. Matilda was determined to continue his work and her own. In 1890, John Wesley Powell hired her as an assistant ethnologist at the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution. She was the first woman hired for this role. She first organized James's notes. Later, she took on a bigger role and led her own research.

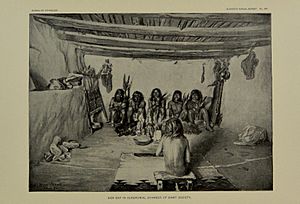

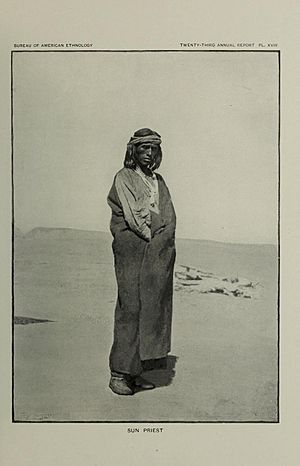

Because it was unusual for a woman to work alone, Powell assigned Matilda an assistant, May S. Clark. Clark stayed with Matilda until Matilda's death. Clark took many of the photos for Matilda's main book, The Zuñi Indians: Their Mythology, Esoteric Fraternities, and Ceremonies (1904). Powell encouraged using cameras to record ethnology. Matilda used photos to capture the Zuni and other Indigenous groups. However, her photography sometimes interrupted ceremonies. Matilda continued to study Indigenous peoples in the Southwest U.S.

Matilda still faced challenges. Even though she was paid by the BAE, it was less than men earned. Things slowly changed in the 1890s. More women were allowed into professional groups. Matilda joined the Anthropological Society of Washington (ASW) in 1891. She also joined the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1892.

In 1893, the Chicago's World Fair had exhibits on Native American peoples. Matilda was a judge for the American Ethnology section. She also gave speeches in the Women's Building. In 1896, Matilda returned to the Zuni people to work on her book. Between 1897 and 1902, she had some health problems. Her book, The Zuñi Indians, was supposed to be finished in 1897, but it was delayed.

John Powell became frustrated with the slow progress on her book. He advised that Matilda take a break from work. There are different ideas about why this happened. Some think Powell wanted to remove staff who were slow to publish. Others believe it was common to try and remove successful women from government jobs using health as an excuse. Regardless, Matilda fought to keep her job. This was a very difficult time for her.

In 1904, she finally finished her book. She was able to continue studying different tribes. From 1890 to 1907, Matilda did a lot of fieldwork. She explored ancient ruins in the Zuni River Valley in western New Mexico. She then studied all the other Pueblo tribes in that state. From 1904 to 1910, she did a special study comparing many tribes. These included the Zia, Jemez, San Juan, Cochiti, Nambe, Picarus, Tesuque, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Taos, and Tewa Native Americans.

In 1907, Matilda bought a ranch near San Ildefonso. This became her base for fieldwork. She kept noticing how the Pueblo peoples were changing. In 1911, she wrote a letter to [Frederick Webb] Hodge. She said, "The more I study the Pueblos the vaster the field becomes, and the gradual changing of these people render[s] it of vast importance for students to work continuously while it [sic.] is yet time, for the younger generation perform their rituals with but slight understanding of the ancient beliefs of their people." Matilda Stevenson died in Maryland on June 24, 1915.

Legacy

Items collected by Matilda and James Stevenson are now in the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution. Matilda Stevenson's papers are kept in the Institution's National Anthropological Archives.

One of Stevenson's students was John Peabody Harrington.

Works

Matilda Stevenson wrote these books:

- Zuñi and the Zuñians (1881)

- The Religious Life of the Zuñi Child (1888)

- The Sia (1894)

- The Zuñi Indians: Their Mythology, Esoteric Fraternities, and Ceremonies (1904)

Images for kids

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |