Meeker Massacre facts for kids

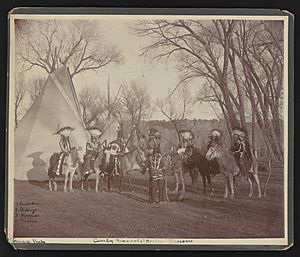

Quick facts for kids Meeker Massacre, leading to White River War / Battle of Milk Creek |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

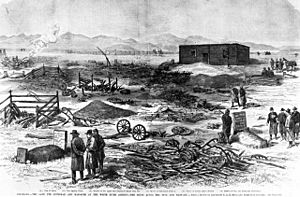

An etching that appeared in the December 6, 1879 edition of "Frank Leslie's Weekly" depicts the aftermath of the Meeker Massacre. Meeker grave at lower left; W.H. Post grave at lower right |

|||||

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

| Ute | |||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Chief Douglas Nicaagat (Jack) |

|||||

| Strength | |||||

| ~700 | ~250 | ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| 24 killed 44 wounded |

19–37 killed 7 missing |

||||

The Meeker Massacre (also known as the Meeker Incident, White River War, or Ute War) happened in Colorado in 1879. It involved a conflict between the Ute Indians and the United States.

On September 29, 1879, a group of Ute Indians attacked the Indian Agency on their reservation. They killed Nathan Meeker, the Indian agent, and ten of his male workers. Five women and children were taken as hostages. Meeker had been trying to change the Utes' way of life. He wanted them to become farmers and Christians, instead of living their traditional nomadic lifestyle.

On the same day, U.S. Army troops were on their way to the Agency. They were led by Major Thomas T. Thornburgh. The Utes attacked these troops at Milk Creek, about 18 miles north of what is now Meeker, Colorado. Major Thornburgh and 13 soldiers were killed. More troops were sent, and the Utes eventually scattered.

This conflict led to the Utes losing most of the land they had been promised by treaty in Colorado. The White River Utes and Uncompahgre Utes were forced to move from Colorado. The Southern Utes also lost some of their land. The Utes' removal opened up millions of acres of land for white settlers.

Contents

Background of the Conflict

In 1879, the Ute Reservation covered most of western Colorado. A treaty in 1868 had given this land to the Utes for their "absolute and undisturbed use." The treaty also said the U.S. government would stop anyone from entering Ute lands without permission.

However, during the 1870s, miners started moving onto the Ute Reservation. The U.S. government did little to stop them. From 1875 to 1879, only a few Army troops were near the Reservation. By 1879, most of these troops were fighting Apaches in New Mexico.

In 1878, Nathan Meeker became the U.S. Indian Agent at the White River Ute Indian Reservation. This was near the present-day town of Meeker, Colorado. Meeker had no experience with Native Americans. He tried to force the Utes to change their customs.

Meeker wanted the Utes to become farmers and Christians. The Utes were used to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, hunting bison and moving with the seasons. They did not want to settle on one piece of land. Meeker made the Utes angry by plowing a field they used for grazing and racing horses.

Also, Frederick Walker Pitkin, the new Governor of Colorado, had promised to make "The Utes Must Go!" a reality. The Governor and other local leaders made exaggerated claims against the Utes. They wanted to remove the Utes from Colorado.

The Conflicts Begin

Attack at White River Agency

Nathan Meeker had a heated argument with a Ute chief. This happened after Meeker insisted the Utes change their way of life. Meeker then asked for military help. He claimed an Indian had attacked him and injured him.

On September 29, 1879, the Utes attacked the Indian Agency. They killed Meeker and ten men who worked there. The dead included Nathan Meeker, Frank Dresser, Henry Dresser, George Eaton, Wilmer E. Eskridge, Carl Goldstein, W.H. Post, Shaduck Price, Fred Shepard, Arthur L Thompson, and Julius Moore.

Ute warriors took some women and children as hostages. They used these hostages to try and get a better deal from the government. The hostages were held for 23 days. Two of the captives were Meeker's wife, Arvilla, and his daughter, Josephine. Josephine had just finished college and was working as a teacher and doctor.

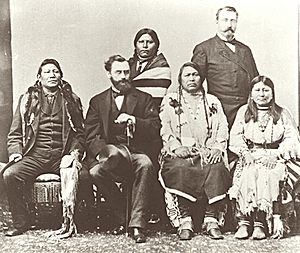

Chief Ouray of the Uncompahgre Utes was not involved in the fighting. He tried to keep the peace after the attacks. Chief Ouray and his wife, Chipeta, helped negotiate the release of the women and children hostages.

Attack on U.S. Army Troops at Milk Creek

Major Thomas Tipton Thornburgh led 153 soldiers and 25 militiamen. They left Fort Steele on September 21, 1879. They were going to the White River Indian Agency to help Nathan Meeker. His force included soldiers from the 3rd Cavalry, 5th Cavalry, and 4th Infantry.

On September 29, 1879, Ute warriors attacked Thornburgh's troops at Milk Creek. This happened at the same time as the attack on Meeker's Agency. Ute warriors, led by Chief Colorow, ambushed Thornburgh's forces. This was on the northern edge of the reservation, about 18 miles from the Agency.

Within minutes, Major Thornburgh and 13 men were killed. This included all his officers above the rank of captain. Another 28 men were wounded. Most of their horses and mules were also killed. The surviving troops dug in for defense behind their wagons and the bodies of the animals. One soldier rode quickly to get help.

The U.S. forces held out for several days. Chief Colorow joked with his warriors about the smell of dead animals the troops had to endure. On October 2, 35 African-American cavalrymen, known as Buffalo Soldiers, arrived to help. They were from the 9th Cavalry at Fort Lewis. Captain Francis Dodge and Sergeant Henry Johnson were among these reinforcements.

Over the next three days, 38 of the 42 animals Captain Dodge brought were killed. The other four were wounded. Dodge focused on securing the camp and getting drinking water. Henry Johnson was in charge of the guards. He checked on his men in the outposts under heavy fire. Some stories say the Utes would not shoot at the black soldiers when they got water from the creek.

Troops Rescued at Milk Creek

Larger U.S. Army relief groups were sent from Fort Steele and Fort D.A. Russell in Wyoming. Colonel Wesley Merritt led five groups of troops from the 5th Cavalry Regiment, about 350 soldiers. They traveled by train and then marched to Milk Creek. They reached the surviving forces on October 5.

By the time Colonel Merritt arrived, the Utes had already left. The 9th Cavalry later returned to New Mexico to fight Chief Victorio. The other regiments stayed at the site of the former Indian Agency for the winter. In the spring, the U.S. Army built a camp on the White River. The Army stayed there until 1883. A few buildings from the Army Camp still remain. Some Utes escaped and spent the winter in North Park. Their traditional homes, called wickiups, can still be seen there.

Aftermath of the Conflict

Meeker and his ten associates were killed. The army and militiamen lost 13 dead and 44 wounded. Most of these losses happened in the first 24 hours of the battle. Eleven soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their bravery. About thirty others were also honored for their heroic actions. These included Sergeant Henry Johnson and Captain Francis Dodge. Chief Jack estimated that 19 Ute warriors were killed and seven were missing. Other sources say the Utes lost 37 killed in total.

Increased Hostility

After the Milk Creek and White River incidents, there was strong anger toward the Utes. This was true both in Colorado and within the American army. There was growing pressure to remove the Utes entirely from the state, or even to wipe them out. People had wanted to move the Utes off their land even before the war. So, the fighting just made these feelings stronger.

Early Peace Talks

Treaty talks happened because Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz stepped in. He stopped any military action against the Utes until the hostages were safely released. Charles Adams, a former Indian agent, managed to get the White River Utes to release the hostages. Talks began in November 1879 at the Los Piños Indian Agency.

Ute Removal Act

When these talks did not work, Congress called everyone to Washington in 1880. A treaty was agreed upon. The White River Utes agreed to move to the Uintah Reservation in Utah. The Uncompahgre Utes, who had not been part of the uprising, were supposed to stay in Colorado on a smaller piece of land.

Later, this plan changed. The Uncompahgre Utes were also moved to Utah. The Ute Removal Act took away 12 million acres of land that had been promised to the Utes forever. Congress insisted that the Utes be forced to leave Colorado and move to eastern Utah. The Southern Ute were also supposed to move. However, it was hard to find them land in nearby states. They ended up staying on a reservation along the border of Colorado and New Mexico.

After their removal, the Uncompahgre Utes named their new land reserve the Ouray Reservation. This was named after Chief Ouray, who died in August 1880. The Uncompahgres were moved on August 28, 1881, with the army escorting them. The army forced the Utes to move, but it also protected them from angry settlers who followed them.

The White River Utes were harder to move. The Indian Bureau encouraged them to go to the Uintah Reservation. They did this by sending their food and land payments there. The White River Utes remained mostly nomadic. They were still seen as a threat to return to Colorado. Because of this, the army planned a military post next to the Utah reservations.

When Chief Jack and the White River Utes fled back to Colorado, the army found them on April 28, 1882. Soldiers killed Chief Jack while he was trying to avoid capture and being forced back to the Uintah Reservation. The removal of the Utes from most of their lands in Colorado marked the end of the White River War.

|

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |