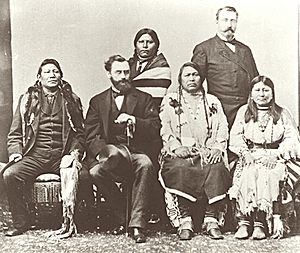

Ouray (Ute leader) facts for kids

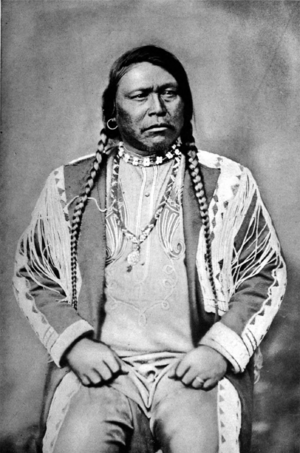

Ouray (born 1833 – died August 24, 1880) was an important Native American chief. He led the Tabeguache (Uncompahgre) band of the Ute tribe. This tribe lived in what is now western Colorado.

The U.S. government recognized Ouray as a key Ute leader. He often traveled to Washington, D.C. to talk about his people's future. Ouray grew up in Taos, a town with many cultures. He learned to speak several languages. This skill helped him greatly in his negotiations. He met with Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and Hayes. People called him the "man of peace" because he worked hard for treaties with settlers and the government.

After the Meeker Massacre in 1879, Ouray went to Washington, D.C. again in 1880. He tried to get a treaty so the Uncompahgre Ute could stay in Colorado. However, the next year, the U.S. government forced the Uncompahgre and White River Ute to move. They were sent to reservations in what is now Utah.

Contents

Ouray's Early Life

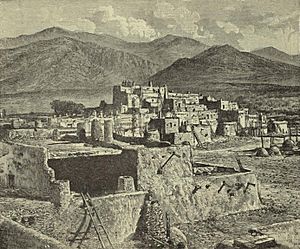

Ouray was born in 1833 near the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. His father, Guera Murah, was a Jicarilla Apache who joined the Ute tribe. His mother was Uncompahgre Ute.

Ouray had a brother named Quench. Their mother died soon after Quench was born. Their father remarried. Around 1843 or 1845, Ouray and his brother lived with a Spanish-speaking couple. Their father went back to Colorado. He became a leader of the Tabeguache Ute band.

Ouray stayed in Taos and received a Catholic education. He learned many languages, including Ute, Apache, Spanish, and English. He also learned sign language. These skills were very useful when he talked with both white settlers and other Native American tribes. He spent his youth working with Mexican sheepherders. He also helped transport wood and supplies on the Santa Fe Trail.

In 1850, Ouray and his brother joined their father in Colorado. Their father died shortly after. Ouray was known as the best rider, hunter, and fighter in his band. He became an enforcer, like a police chief, and then a sub-chief. He fought against the Kiowa and the Sioux tribes.

Chief and Negotiator

Becoming a Chief

In 1860, Ouray became the chief of his band when he was 27 years old. That year, he explored the Uncompahgre and Gunnison River valleys. He was worried by how many white miners and settlers were moving onto Ute lands. Ouray understood that fighting the settlers would not stop them. Instead, he believed that making treaties was the best way to protect his people's interests.

Working for Peace

Ouray was known as the "White man's friend." He was very important to the government in negotiating with his tribe. The Utes kept all the treaties he made. Ouray protected his people's interests as much as he could. He also showed them how to live a more settled life.

Ouray wanted peace between different groups. He believed that war with white settlers could destroy the Ute tribe. However, some Utes thought he was a coward for always wanting to negotiate. In 1874, his brother-in-law tried to attack him with an axe. This happened because he was upset by the treaties Ouray made.

Treaty of Conejos (1863)

Colorado Territory was created in 1861. In 1862, Ouray convinced the Utes to negotiate a treaty with the government. This treaty was meant to protect their traditional lands. Kit Carson noticed that settlers were mining and living in Ute hunting grounds. This made game scarce. Carson helped Ouray write a treaty. Ouray was part of the Ute group and acted as a translator. He met with Governor John Evans. Then, he traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet President Abraham Lincoln.

Ouray helped negotiate the Treaty of Conejos in 1863. This treaty reduced Ute lands by half. They lost all their lands east of the Continental Divide. This included healing waters at Manitou Springs and sacred land on Pikes Peak. The treaty guaranteed them the western one-third of Colorado. The Utes agreed to allow roads and military forts on their land. To encourage farming, they were promised sheep, cattle, and $10,000 in goods over ten years. However, the government often did not provide these promised items. Since game was scarce, many Utes continued to hunt on their old lands. They were later moved to reservations in 1880 and 1881.

Treaty of 1868

Around 1866, some Native Americans stole livestock and caused problems for new settlers. After an uprising by Chief Kaniatse, Colonel Kit Carson helped negotiate a treaty with Ouray and other Ute leaders in 1867. Meanwhile, the government wanted more Ute land. Ouray was hesitant to give up more land because the government had not kept its promises to provide supplies. However, many Native Americans were in great need. So, Ouray agreed to be part of another delegation.

In 1868, Ouray, Nicaagat, and Kit Carson helped negotiate a new treaty. This treaty created a reservation for the Ute in western Colorado. It included Indian Agencies with a school, blacksmith shop, sawmill, and warehouse. The Utes lost a small amount of land. But Ouray hoped that having a government presence would protect their remaining lands. Forty-seven Ute chiefs signed this treaty.

Brunot Treaty of 1873

Silver was discovered in the San Juan Mountains in 1872. The government wanted to negotiate for more land again. Ouray was very sad because his five-year-old son had been taken during a Sioux attack years earlier. U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Felix Brunot used Ouray's grief. He brought a 17-year-old orphan to meet Ouray and Chipeta in Washington, D.C. This was an attempt to make Ouray give up mining land. The boy was not Ouray's son. He did not speak Ute and did not want to go with Ouray. This meeting was upsetting for Ouray.

In 1873, with Ouray's help, the Brunot Agreement was approved. The United States gained the valuable mining land they wanted. In return, the Native Americans were supposed to receive supplies over time. Ouray was given land and a house in the Uncompahgre Valley. However, the government was again slow to provide the promised supplies. Ouray's negotiations for this treaty included a meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant.

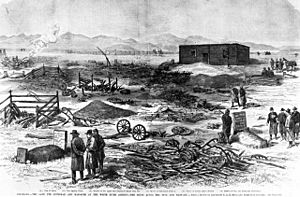

Meeker Massacre and Its Aftermath

Tensions grew after the Meeker Massacre in 1879 at the White River Indian Agency. Nathan Meeker, the agent, did not understand the Utes' love for horses. He plowed their race track and tried to force the nomadic Utes to farm. Meeker also asked for military help. A group of Ute men, led by Chief Douglas, tried to make peace with Meeker. But a fight broke out. This made it very hard to negotiate peace between Native Americans and white settlers. Local settlers demanded that the Utes be moved.

When Ouray learned about the massacre, he acted as the head of the Utes. He asked the warriors to stop fighting and release the hostages to him. The hostages, including Josephine Meeker, were brought to Ouray's house. His wife, Chipeta, cared for them there.

Final Treaty and Relocation

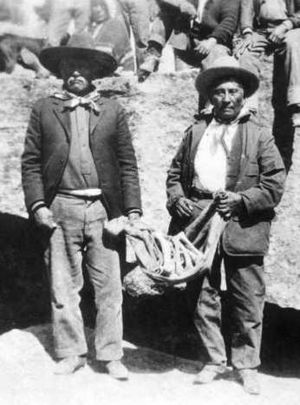

The U.S. government formed a group to decide where the Utes would live. Ouray and Chipeta went to Washington, D.C. in 1880 for the final treaty talks. President Rutherford B. Hayes met Ouray in Washington, D.C. He said Ouray was "the most intellectual man I've ever conversed with."

When Ouray returned to Colorado, he was very ill with Bright's disease. He still traveled to the Ignacio Indian Agency office. He wanted to make sure the Southern Utes signed the treaty.

Later, many Utes were moved to the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in Utah. Other Utes were placed on two reservations in Colorado: the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and the Southern Ute Indian Reservation.

Ouray's Personal Life

Ouray's first wife, Black Mare, died after their son was born. His son was named Queashegut, also called Pahlone or "Paron" (apple) by Ouray. In 1859, Ouray married sixteen-year-old Chipeta. Her Ute name meant "White Singing Bird." She had been caring for Ouray's son since Black Mare's death.

In 1860 or 1863, Ouray took his five-year-old son, Queashegut, on a buffalo hunt. Their camp near Fort Lupton was attacked by 300 Sioux warriors. Queashegut left the tepee where he was hiding with Chipeta to follow Ute warriors. After the fight, they could not find him. He had been captured and traded to an Arapaho band. Ouray never saw his son again and was deeply saddened. He searched for his son for the rest of his life. He worried his son might be raised to fight against his own people. In 1866, Ouray and Chipeta adopted two girls and two boys while visiting Kit Carson at Fort Garland.

Ouray's sister, Shawsheen, was taken by the Arapaho in 1861 or 1863. Soldiers found her two years later, but she was scared and escaped. Utes later found her and brought her back to Ouray's tribe.

Ouray had several homes in Colorado, including one near the town of Ouray. For twenty years, Ouray and Chipeta lived on a farm by the Uncompahgre River near Montrose. Their farm had 300 acres, with pasture and 50 acres of irrigated farmland. Their six-room adobe house was well-furnished, even having a piano and fine china. Today, the Ute Indian Museum is located on their original homestead in Montrose. Chipeta was a Methodist, and Ouray was an Episcopalian. Ouray kept his long Ute-style hair, but he often dressed in European-American clothing.

Ouray died on August 24, 1880, near the Los Piños Indian Agency in Colorado. His people secretly buried him near Ignacio, Colorado. Forty-five years later, in 1925, his bones were reburied in a special ceremony. Buckskin Charley and John McCook led this event at the Ignacio cemetery.

An article from 1928 said Ouray "saw the shadow of doom on his people." A 2012 article noted, "He sought peace among tribes and whites, and a fair shake for his people." Ouray faced the difficult task of leading a once-powerful tribe that controlled millions of acres in the Rocky Mountains.

Ouray's Legacy and Honors

Ouray's obituary in The Denver Tribune newspaper stated: In the death of Ouray, one of the historical characters passes away. He has figured for many years as the greatest Indian of his time... Ouray is in many respects...a remarkable Indian...pure instincts and keen perception. A friend to the white man and protector to the Indians alike.

Places Named for Ouray

Many places are named in Ouray's honor:

- Camp Chief Ouray, located in Granby, Colorado.

- Mount Ouray in the Sawatch Mountain Range and Ouray Peak in Chaffee County, both in Colorado.

- Ouray County and its county seat, the town of Ouray in Colorado.

- The community of Ouray, Utah.

- SS Chief Ouray, a World War II liberty ship, later named USS Deimos.

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |