Nicaagat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

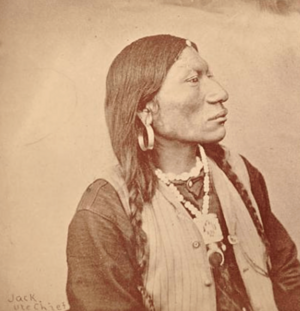

Nicaagat

|

|

|---|---|

Photographed by George W. Kirkland, 1873, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

|

|

| Born | 1840 |

| Died | ca. April 29, 1882 |

| Other names | Ute Jack, Captain Jack, Chief Jack |

| Occupation | Ute chief |

Nicaagat (born 1840, died 1882) was a brave Ute warrior and leader. His name means "leaves becoming green." He was also known as Chief Jack, Captain Jack, and Ute Jack.

Nicaagat led a group of Ute warriors against the United States Army. This happened when the Army entered the Ute reservation at Milk Creek. This event started the Battle of Milk Creek. Before the fight, Nicaagat tried to meet with Major Thomas Tipton Thornburgh. He wanted to warn him that crossing Milk Creek onto the White River Ute reservation would be seen as an attack. When the Army entered the reservation, a Ute warrior from Nicaagat's group shot and killed Major Thornburgh.

After the battle, Nicaagat traveled all the way to Washington, D.C.. He spoke to Congress to explain why his people acted the way they did.

When he was a boy, Nicaagat became an orphan. He was taken in by a family and grew up with white children. He went to school and church with this family. After several years, he ran away because he was treated poorly. He traveled to Colorado and joined the White River Utes. He married a young woman from the tribe. Nicaagat became a leader for the younger men. He also worked as a scout for General George Crook during the Sioux Wars in 1876 and 1877.

Contents

The Ute People: A Brief History

Nicaagat was a Ute chief from Colorado. The Utes were a nomadic people. This means they moved around a lot. They hunted large and small animals across their vast lands in family groups. Different Ute family groups would meet throughout the year. They held religious and traditional ceremonies, like the Bear Dance. They also gathered foods like berries, roots, and nuts, and they fished. The Utes lived in tipis and wickiups.

In the 1800s, traders and miners started moving onto Ute land. Then, more settlers followed. These newcomers brought diseases like smallpox that harmed the Ute people.

The Utes tried to negotiate with the white settlers. But this often led to the Utes losing their land. Eventually, the Ouray and Uintah reservations were created for them. Today, there are three main Ute groups:

- The Uintah Utes in Utah.

- The Uncompahgre Utes in Colorado.

- The White River Utes (also called Nüpartka) in Colorado.

The White River and Uncompahgre Utes lived on a Colorado reservation. This was set up by the Treaty of 1868. In the 1870s, Ute tribal land in Colorado was huge. It covered 12 million acres west of the Continental Divide. This land included areas around Ignacio, Durango, Meeker, and Aspen.

Nicaagat's Early Life and Leadership

Nicaagat was born in 1840. He was of Ute and Apache heritage, or possibly a Goshute. He became an orphan when he was very young in Utah. He was taken in by a family with white children. This family had him baptized and sent him to school. He also went to church with them. He lived with this family for several years. One day, he ran away. He found a saddled horse and escaped into the mountains. Other Native Americans helped him on his journey.

He met his future wife at his first annual Bear Dance after his escape. His wife chose him, and her parents agreed to the marriage. Nicaagat became a member of the White River Utes. He quickly became a respected leader among the young men.

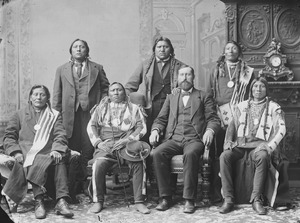

In January 1868, Nicaagat went to Washington, D.C. with Chief Ouray and other leaders. Their goal was to sign a treaty. This treaty would define the borders of the Ute people's land.

Nicaagat learned to speak English very well. Because of this, he served as a scout for General George Crook in 1876 and 1877. General Crook was fighting the Sioux, who were enemies of the Ute people. Working with Crook, Nicaagat saw firsthand what could happen when the military entered a Native American reservation.

The Meeker Massacre and Battle of Milk Creek

Nathan Meeker became the Indian agent for the White River Ute Agency in 1878. Meeker did not like the traditional Ute ways of life. He did not approve of them using pasture land for race horses. He ordered the Utes to start farming. He even told them to use their race horses to plow fields. This caused a lot of tension between the Utes and Meeker.

Ute leaders, including Ouray, his wife Chipeta, Nicaagat, Colorow, and Black Hawk, tried to solve the problems. They wanted to find a peaceful solution between the Utes and the United States government.

Nicaagat returned to the Ute reservation. He thought it was ridiculous that Meeker wanted to turn brave Ute hunters into gardeners. Meeker reportedly said that half of their valuable horses should be shot. He also wanted the Utes' race track plowed over for crops. Meeker refused to let them use other nearby land for farming. There were also arguments about building irrigation ditches. As tensions grew, Meeker sent warnings to the government. He also gave information to Denver newspapers. Nicaagat met with Colorado Governor Frederick W. Pitkin. He told the governor that Meeker's statements were lies. Major Thomas Tipton Thornburgh from Fort Steele was sent to Colorado to deal with the situation.

Nicaagat and other warriors met Thornburgh at Fortification Creek. They met again at Peck's Trading Post near today's Craig, Colorado. They wanted to understand Thornburgh's intentions. Nicaagat told him that the soldiers should not cross into the reservation. Doing so would go against the Ute's treaty with Governor Pitkin. Nicaagat suggested that five soldiers and five Utes go together to the Indian agency to meet with Meeker. Thornburgh discussed this idea with his scouts. They warned him to be careful, saying the suggestion might be a trick. Thornburgh did not believe the Utes were dangerous, based on past experiences. However, he decided to follow his original orders. This meant sending his full force onto the reservation. Thornburgh told Nicaagat that he needed to see the situation for himself before making a plan.

Nicaagat left the army camp and went to Peck's trading post. There, he bought 10,000 rounds of ammunition, which was better than the military's. While he was away, the Utes at the agency held war dances. They remembered the Sand Creek Massacre. In that event, 700 soldiers attacked Black Kettle's village of sleeping women and children while the Cheyenne men were hunting.

When the military crossed Milk Creek onto the Ute reservation, it was seen as an invasion and an act of war. Nicaagat led the Meeker Uprising and the Battle of Milk Creek on September 29, 1879. He claimed that he was the one who killed Major Thomas Tipton Thornburgh. Meeker and 11 other people at the agency were killed during the Meeker Massacre. After this, military forces were set up at the site of Meeker, Colorado. The Utes feared another massacre like the one at Sand Creek. So, they surrendered on October 5.

General Hatch held a special meeting to study the Meeker Massacre and Battle of Milk Creek. He decided that no Utes would be tried for fighting the United States military. However, those involved in killing or kidnapping people from the Indian Agency would need to be brought in. Colorow and Nicaagat were chosen to bring certain individuals, like Quinkent, to a trial outside of Colorado. Nicaagat was never forgiven by some Utes for this. So, he left the reservation with his wife and children.

Later Years and Legacy

Nicaagat went to live on a Shoshone reservation in Wyoming. Seven cavalry men came to find him. They said he was off the reservation. The Indian Agency had asked for his arrest. This happened on April 29, 1882, near Fort Washakie, Wyoming. Soon after, he escaped and ran into a nearby tipi. He found a carbine (a type of rifle) and killed a soldier, Sergeant Richard Casey. Nicaagat was shot in the arm. The tipi he ran into was then fired upon by soldiers using a howitzer (a type of cannon), and he was killed.

A portrait of Nicaagat was made by Joseph Lee Hershel in the 1930s. It is now part of the collection at the History Colorado Center.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |