Mikhail Bakunin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mikhail Bakunin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin

May 30, 1814 Pryamukhino, Tver Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Kuvshinovsky District, Tver Oblast, Russia)

|

| Died | July 1, 1876 (aged 62) |

| Era | 19th century philosophy |

| Region |

|

| School |

|

| Signature | |

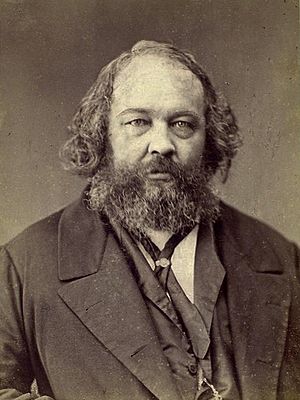

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (1814–1876) was a Russian thinker and activist. He is known for being a founder of collectivist anarchism. This idea suggests that society should be organized without a government. He is seen as one of the most important figures in the history of anarchism. He also greatly influenced revolutionary socialist ideas.

Bakunin grew up in a family estate called Pryamukhino in Russia. In 1840, he went to study in Moscow and then in Berlin. He hoped to become a university professor. Later, in Paris, he met famous thinkers like Karl Marx and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. These meetings changed his ideas a lot.

As his ideas became more radical, his dream of being a professor ended. He was forced to leave France because he spoke out against Russia's control over Poland. In 1849, he was arrested in Dresden for being part of a rebellion. He was sent back to Russia and put in prison. He was held in the Peter and Paul Fortress and later in the Shlisselburg fortress. In 1857, he was sent to Siberia.

Bakunin managed to escape from Siberia. He traveled through Japan to the United States and then to London. There, he worked with Alexander Herzen on a newspaper called Kolokol (The Bell). In 1863, he tried to join an uprising in Poland but couldn't reach it. He then spent time in Switzerland and Italy.

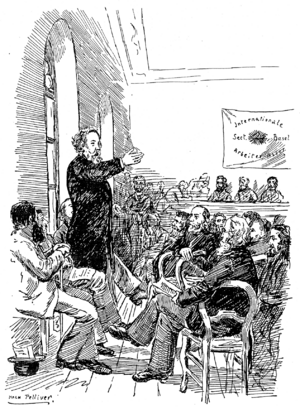

In 1868, Bakunin joined the International Workingmen's Association. This group was for workers around the world. He led a group within it that believed in anarchism. At a meeting in 1872, Bakunin and Marx had a big disagreement. Marx believed the state could be used to bring about socialism. Bakunin and his group wanted to replace the state with groups of self-govergoverning workplaces and communities. Bakunin was expelled from the International. He then started the Anti-Authoritarian International. From 1870 until his death in 1876, Bakunin wrote many important books like Statism and Anarchy and God and the State. He also kept working with worker and farmer movements in Europe.

Bakunin is remembered as a key figure in anarchism. He was a strong opponent of Marxism. He famously predicted that Marxist governments would become dictatorships. His book God and the State is still read today. He influenced many thinkers and groups, including the Industrial Workers of the World and anarchists in the Spanish Civil War.

Contents

Mikhail Bakunin's Life Story

Early Life and Education

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was born on May 18, 1814. He came from a noble Russian family. They lived in a village called Pryamukhino. His father was a diplomat who worked in Italy and France. His mother was much younger than his father. Her family had been important in Russia since the 1400s.

When he was 15, Bakunin went to Saint Petersburg. He joined the Artillery School to become a soldier. In 1833, he became an officer. He was sent to serve in Minsk. He didn't like army life much. He spent his free time reading and learning on his own. In 1835, he returned to his village. Even though his father wanted him to stay in the military, Bakunin went to Moscow to study philosophy.

Discovering Philosophy and New Ideas

In Moscow, Bakunin quickly made friends with students who loved philosophy. They studied the ideas of German thinkers like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. By 1836, Bakunin had translated some of their works into Russian. He also met important Russian thinkers like Alexander Herzen. During this time, he started to develop his ideas about Pan-Slavism, which was about uniting Slavic peoples.

In 1840, Bakunin went to Berlin. He planned to become a university professor. But he soon joined groups of young thinkers who were interested in socialism. In 1842, he wrote an essay where he said that "the passion for destruction is a creative passion." This showed his growing belief in revolution.

After studying in Berlin, Bakunin moved to Dresden. He read more about socialism and became very passionate about it. He gave up his dream of being a professor. He decided to spend his time promoting revolution. The Russian government found out about his activities. They ordered him to return to Russia, but he refused. His property was taken away. He then went to Switzerland.

Early Political Views

Before he became an anarchist, Bakunin was interested in a left-wing type of nationalism. He focused on Eastern Europe and Russia. He believed that Slavic people should be free and democratic. Even later, as an anarchist, he still thought national freedom was important. But he believed it should be part of a bigger social revolution.

In Switzerland, Bakunin met German communists. He sometimes called himself a communist. He wrote articles about communism. He moved to Brussels, where he met many Polish nationalists. He disagreed with them because they didn't want to give rights to non-Polish people in their lands. He also didn't like their religious views.

In 1843, Bakunin went to Paris. This city was a center for political ideas in Europe. He met Karl Marx and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. They greatly impressed him. In 1844, the Russian Emperor took away Bakunin's noble status. He also took his land and exiled him to Siberia for life. Bakunin responded by writing a letter that criticized the Emperor. He called for democracy in Russia and Poland.

In 1847, Bakunin gave a speech about Poland. He called for an alliance between Polish and Russian people against the Emperor. He hoped for the end of strict rule in Russia. Because of this speech, he was expelled from France and went back to Brussels.

Revolutions of 1848 and Arrest

The European Revolutions of 1848 made Bakunin very excited. He hoped for big changes in Russia. He received money from the French government to support a plan for a Slavic federation. This federation would free people under the rule of Prussia, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. He traveled to Germany and then to Prague.

In Prague, he took part in the First Pan-Slav Congress. After the congress, there was an uprising that Bakunin supported. But it was quickly stopped by force. In 1848, Bakunin wrote his Appeal to the Slavs. In it, he suggested that Slavic revolutionaries should join with Hungarian, Italian, and German revolutionaries. Their goal would be to overthrow the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Prussian empires.

Bakunin played a big part in the May Uprising in Dresden in 1849. He helped organize the defense against Prussian soldiers. He was captured and held for 13 months. He was sentenced to death, but his sentence was changed to life in prison. This allowed him to be sent to Russia and Austria, who also wanted to put him on trial. In 1851, he was finally handed over to the Russian authorities.

Imprisonment and Escape

Bakunin was taken to the Peter and Paul Fortress in Russia. He spent three years there. Then he spent four more years in the Shlisselburg fortress. Life in prison was very hard. He became sick and lost all his teeth.

After the death of Emperor Nicholas I, the new Emperor Alexander II refused to pardon Bakunin. But in 1857, his mother's pleas were heard. He was allowed to go into permanent exile in Tomsk, a city in Siberia. A year later, he married Antonina Kwiatkowska.

In 1858, Bakunin was visited by his cousin, General Count Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky. Muravyov was a liberal and helped Bakunin get a job. This job allowed him to move to Irkutsk, the capital of Eastern Siberia. Here, Bakunin joined a group that discussed politics. They even thought about creating a "United States of Siberia" that would be independent from Russia.

Thanks to his cousin's influence, Bakunin was able to keep his job without doing much work. In 1861, Bakunin left Irkutsk. He pretended to be on a business trip. He managed to get on a Russian warship and then on an American ship. He sailed to Japan, then to San Francisco, and finally to London. He arrived in London on December 27, 1861. He immediately went to see his friend Herzen.

Return to Europe and Anarchist Ideas

Back in Europe, Bakunin quickly became involved in revolutionary movements again. He was very impressed by Giuseppe Garibaldi, an Italian leader. Bakunin wanted Garibaldi to join a movement to unite Italians, Hungarians, and South Slavs against Austria and Turkey.

In 1863, a Polish uprising began. Bakunin tried to join it but failed. He then focused on moving to Italy. He arrived in Italy in January 1864. It was here that he really started to develop his anarchist ideas. Bakunin planned a secret group of revolutionaries. This group would spread ideas and prepare for direct action. He called it the International Brotherhood.

By 1866, Bakunin's secret group had members in many countries. These included Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Britain, France, Spain, and Italy. He also had Polish and Russian members. In his Catechism of a Revolutionary (1866), he spoke against religion and the state. He called for "the absolute rejection of every authority."

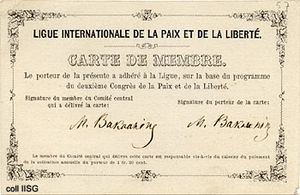

In 1868, Bakunin joined the French League of Peace and Freedom. He wrote an essay called Federalism, Socialism, and Anti-Theologism. In this essay, he supported a federalist socialism. This meant that different groups and regions would govern themselves. He said that "liberty without socialism is privilege, injustice; socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality." At a meeting in 1868, Bakunin and other socialists left the League. They started their own group called the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy.

The First International and Anarchism

In 1868, Bakunin joined the First International, a big organization for workers. He was very active until he was expelled in 1872. Bakunin helped set up the Italian and Spanish parts of the International.

Between 1869 and 1870, Bakunin worked with a Russian revolutionary named Sergey Nechayev. However, Bakunin later disagreed with Nechayev's methods. Nechayev believed that any means were acceptable to achieve revolutionary goals.

In 1870–1871, Bakunin led an uprising in Lyon, France. He wanted to turn a war into a social revolution. He called for workers and farmers to unite. He suggested a system of self-governing communities. He believed that actions were the best way to spread ideas.

These ideas were very similar to the Paris Commune of 1871. Bakunin strongly supported the Commune. He saw it as a "rebellion against the State." He praised the people of the Commune for rejecting both the state and a revolutionary dictatorship. He defended the Commune against critics.

Bakunin's disagreements with Karl Marx became very clear. Marx and his followers believed the working class should take political power. Bakunin and his group believed in direct revolutionary action. They wanted to abolish the state and capitalism right away. Bakunin was a strong opponent of Marx. He warned that communist governments would become authoritarian.

Bakunin's Final Years

In 1872, the groups that agreed with Bakunin formed their own International. They adopted a revolutionary anarchist program. Bakunin accepted some of Marx's ideas about capitalism. But he thought Marx's methods would harm the social revolution. He strongly criticized "authoritarian socialism" and the idea of a "dictatorship of the proletariat." He believed that no dictatorship could bring freedom. Freedom, he said, could only be created by freedom itself.

In 1874, Bakunin moved to a villa in Switzerland with his wife and three children. His daughter, Maria Bakunin, became a famous chemist. Bakunin died in Bern, Switzerland, on July 1, 1876. His grave is in the Bremgarten cemetery. His epitaph says: "Remember him who sacrificed everything for the freedom of his country." In 2015, a new bronze portrait was added to his grave. It has his quote: "By striving to do the impossible, man has always achieved what is possible."

What Were Bakunin's Main Ideas?

Bakunin's political ideas rejected all forms of government and strict power. He believed that no one should have power over others. This included the idea of God and any kind of government, even one chosen by everyone. He wrote that human freedom means obeying natural laws because you understand them, not because someone else forces them on you.

He also rejected any special positions or classes in society. He thought that social and economic differences were not fair. He believed that both capitalism and the state prevented people from being truly free. He said that being in a special position, whether politically or economically, harms a person's mind and heart. Bakunin's main ideas were about:

- Freedom

- Socialism

- Federalism (local self-rule)

- Anti-religion

- Materialism (believing only in what is physical)

He also criticized Marxism. He predicted that if Marxists took power, they would create a one-party dictatorship. He said it would be "all the more dangerous because it appears as a sham expression of the people's will."

Why Did Bakunin Oppose Religion?

Bakunin believed that religion came from people's ability to think and imagine. He thought religion was kept alive by teaching and by people following what others do. He also believed that poverty and suffering made people turn to religion. Religion, he said, promised salvation in the afterlife.

Bakunin argued that powerful people use religion to control others. Religious people often obey priests because they believe priests speak for God. If God is all-knowing and all-powerful, then what God says cannot be questioned. This means people cannot decide what is right or wrong for themselves. Bakunin thought that religion was always about authority.

In his book God and the State, Bakunin wrote that the idea of God takes away human reason and freedom. He famously said that "if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish Him."

How Did Bakunin Plan for Social Change?

Bakunin believed that workers and farmers should organize themselves from the ground up. They would create local groups that would then connect with each other. These groups would show how the future society would work.

He supported an idea called syndicalism. This meant that trade unions would help workers now. They would also be the basis for a social revolution. In this revolution, workers would take over workplaces. The unions would manage these workplaces democratically. Bakunin believed that workers' unions would "take possession of all the tools of production as well as buildings and capital."

Bakunin also thought it was important to organize people in working-class neighborhoods. He included the unemployed and the very poor. He believed these groups could start a social revolution.

What is Collectivist Anarchism?

Bakunin's type of socialism was called "collectivist anarchism." It aimed for political and economic equality for everyone. This meant equal opportunities for every child, and equal resources for adults to earn a living through their own work.

Collectivist anarchism wanted to get rid of both the government and private ownership of factories and farms. Instead, these things would be owned by everyone. Workers themselves would control and manage them. After this change, money would be replaced by "labor notes." Workers' pay would be decided by democratic groups. It would be based on how hard the job was and how much time they worked. People would use these notes to buy goods in a shared market.

Bakunin's Disagreement with Karl Marx

The arguments between Bakunin and Karl Marx showed the big differences between anarchism and Marxism. Bakunin strongly disagreed with Marx's idea of a "dictatorship of the proletariat." This was a new state that would supposedly represent the workers. Bakunin argued that the state should be removed immediately. He believed all forms of government eventually lead to unfair rule.

He also disagreed with the idea that a small group of revolutionary leaders should guide the workers. Bakunin insisted that revolutions must be led directly by the people. He said that any "enlightened elite" should only influence others by remaining "invisible."

Bakunin believed that "freedom without socialism is privilege and injustice; and that socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality." He thought that Marxists wanted to use the state and dictatorship as a way to freedom. But he argued that to free people, you cannot first enslave them.

Even though they disagreed, Bakunin respected Marx's knowledge. He even started translating Marx's book Das Kapital into Russian. Marx also recognized Bakunin's abilities as a leader.

Bakunin is sometimes seen as the first person to talk about a "new class." This class would be made up of smart people and government workers. They would run the state in the name of the people, but really for their own benefit. Bakunin said that the state always belongs to a special group. When all other groups are gone, the state becomes controlled by the government workers.

What is Federalism?

By federalism, Bakunin meant organizing society "from the bottom up." This would be based on free groups and connections. Society would be organized around the "absolute freedom of individuals, of the productive associations, and of the communes." Every person, group, community, region, and nation would have the right to decide for themselves. They could choose to join or not join with others.

What Did Bakunin Mean by Liberty?

For Bakunin, liberty wasn't just an idea. It was a real thing based on everyone having equal freedom. In a positive way, liberty meant "the fullest development of all the abilities of every human being." This would happen through education, training, and good living conditions. This kind of liberty, he said, can only happen when people are together in society.

In a negative way, liberty was "the rebellion of the individual against all authority." This included authority from God, from groups, or from other people.

What is Materialism?

Bakunin rejected religious ideas about a supernatural world. He believed that everything could be explained by science and the physical world. He thought that life, chemical reactions, electricity, light, and heat were all different parts of what we call matter. For Bakunin, science's job was to observe facts and find the general laws that explain how the physical and social world develops.

Workers, Peasants, and the Poor

Bakunin had different ideas from Marx about who would lead a revolution. Marx believed the working class was the main revolutionary group. But Bakunin thought that farmers and even the very poor (like the unemployed or criminals) could also play a big role.

Bakunin focused a lot on organizing "the rabble" and "the great masses of the poor and exploited." He believed these people, who were often ignored by unions, were important for starting a social revolution.

Bakunin's Impact and Criticisms

Bakunin had a huge impact on worker, farmer, and left-wing movements. His ideas became less known after Marxist governments rose to power in the 1920s. But after those governments fell, and people saw how similar they were to the dictatorships Bakunin predicted, his ideas became popular again. Bakunin is remembered as a key figure in anarchism. He is also known for opposing Marxism and for his predictions about Marxist governments. His book God and the State has been translated many times.

Bakunin's biographer, Mark Leier, says that Bakunin influenced many later thinkers. These include Peter Kropotkin and Errico Malatesta. He also influenced groups like the Industrial Workers of the World and Spanish anarchists in the Spanish Civil War. His ideas still influence modern-day activists.

Criticisms of Bakunin

Some people have criticized Bakunin for his views on Jewish people. Sociologist Marcel Stoetzler says that Bakunin believed in a "Jewish conspiracy" to control the world. He points out that in Bakunin's Appeal to Slavs (1848), he wrote that the "Jewish sect" was a "true power in Europe." He claimed they controlled business, banking, and journalism.

Alvin Rosenfeld, who studies antisemitism, agrees that Bakunin's antisemitism was connected to his anarchist ideas. For example, when he criticized Marx, Bakunin said that Marx's communism wanted a strong state bank. He believed that "the parasitic Jewish nation" would always use such a bank to benefit themselves.

Rosenfeld explains that Bakunin's antisemitism influenced anti-Jewish ideas in 19th-century Russia. It also left a mark on anarchist thinking. Some groups, like the Narodnaya Volya in Russia, even called for people to revolt against the "Jewish Tsar."

However, Bakunin's biographer, Mark Leier, argues that Bakunin's antisemitism has been misunderstood. He says it appears in only a few pages of his thousands of writings. He also says it was written during heated arguments with Marx. Leier believes it needs to be understood in the context of the 1800s.

Rosenfeld responded that many movements and admirers of Bakunin, like Peter Kropotkin, did not share his antisemitic beliefs.

Mikhail Bakunin's Writings

Books by Bakunin

- God and the State

- Statism and Anarchy

Pamphlets by Bakunin

- Stateless Socialism: Anarchism (1953)

- Marxism, Freedom, and the State (1950)

- The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State (1871)

- The Immorality of the State (1953)

- Revolutionary Catechism (1866)

- The Commune, the Church, and the State (1947)

- Founding of the First International (1953)

- On Rousseau (1972)

- No Gods No Masters (1998)

Articles by Bakunin

- "Power Corrupts the Best" (1867)

- "The Class War" (1870)

- "What is Authority?" (1870)

- "Recollections on Marx and Engels" (1869)

- "The Red Association" (1870)

- "Solidarity in Liberty" (1867)

- "The German Crisis" (1870)

- "God or Labor" (1947)

- "Where I Stand" (1947)

- "Appeal to my Russian Brothers" (1896)

- "The Social Upheaval" (1947)

- "Integral Education, Part I" (1869)

- "Integral Education, Part II" (1869)

- "The Organization of the International" (1869)

- "Polish Declaration" (1896)

- "Politics and the State" (1871)

- "Workers and the Sphinx" (1867)

- "The Policy of the Council" (1869)

- "The Two Camps" (1869)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mijaíl Bakunin para niños

In Spanish: Mijaíl Bakunin para niños

- Anarchism in Russia

- List of Russian anarchists