1838 Mormon War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1838 Mormon War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mormon Wars | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Joseph Smith (de facto) | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 22 killed and unknown wounded unknown civilian deaths |

|||||||

The 1838 Mormon War, also known as the Missouri Mormon War, was a fight between Mormons and other settlers in Missouri. It lasted from August to November 1838. This was the first of three main "Mormon Wars" in the United States.

Members of the Latter Day Saint movement, led by Joseph Smith, had moved from New York to northwestern Missouri starting in 1831. They mostly settled in Jackson County, Missouri. Here, disagreements with non-Mormon residents led to violence. In 1833, Mormons were forced out of Jackson County. They moved to new counties nearby, but problems started again.

On August 6, 1838, the war began after a fight at an election in Gallatin, Missouri. This led to more organized violence between Mormons and non-Mormons, supported by the Missouri Volunteer Militia. A battle at Crooked River in late October caused Lilburn Boggs, the Governor of Missouri, to issue a special order. This order told Mormons to leave Missouri or face death. On November 1, 1838, Joseph Smith surrendered at Far West, Missouri, which was the church's main city. This ended the war. Smith was accused of serious crimes but escaped. He fled to Illinois with about 10,000 Mormons, where they built a new city called Nauvoo.

During the conflict, 22 people died in battles. Many more civilians died from being forced out of their homes in the cold. All the fighting happened in an area about 100 kilometers (60 miles) east and northeast of Kansas City, Missouri.

Contents

- Why Did the Mormon War Happen?

- Why Did the Peace End in 1838?

- New Groups and Tensions

- The Election Day Fight at Gallatin

- Mormons Forced Out of De Witt

- Events in Daviess County

- Battle of Crooked River

- The Extermination Order

- Haun's Mill Massacre

- Surrender at Far West

- Trials and Escape

- What Happened After the War?

- See also

Why Did the Mormon War Happen?

Soon after the Latter Day Saint church was founded in 1830, Joseph Smith said he had received a message. This message said that a special city, called the City of Zion, would be built near Independence, Missouri, in Jackson County, Missouri. His followers believed they would eventually live on this land.

Mormons began to settle in Jackson County in 1831 to build this city. But as the Mormon community grew quickly, tensions rose with the people who already lived there. There were several reasons for these problems:

- Mormons believed they would inherit the land, which was already owned by others.

- Their way of working together economically allowed Mormons to become very strong in local businesses.

- Mormons believed that Native Americans were descendants of ancient Israelites. They tried to convert many Native Americans to their faith.

- Most Mormon settlers came from areas that were against slavery. Missouri was a slave state at the time, which caused more friction.

These tensions led to attacks against Mormon settlers. In October 1833, anti-Mormon groups forced the Mormons out of Jackson County.

The way Mormons were forced out of Jackson County set a pattern. This pattern happened four more times, until Mormons were forced to leave the entire state. Lilburn Boggs, who was a resident of Jackson County and later the Lieutenant Governor, saw these events unfold. One historian described the pattern:

- Leaders and officials would demand Mormons leave.

- Violence would force Mormons to defend themselves.

- This self-defense was then called an "uprising."

- The local militia would step in to stop the "uprising."

- Once Mormons were disarmed, groups would threaten them to make them flee.

After losing their homes and property, the Mormons temporarily settled near Jackson County, especially in Clay County.

Mormons tried to get their land back or get paid for their lost property, but they were not successful. In 1834, Mormons tried to return to Jackson County with a group called Zion's Camp. But this effort also failed because the governor did not give them the support they expected.

New people joining the Mormon faith kept moving to Missouri and settling in Clay County. As the Mormon population grew, tensions in Clay County increased. To keep the peace, Alexander William Doniphan helped pass a law in 1836. This law created Caldwell County, Missouri, specifically for Mormon settlement. Mormons had already started buying land in this new county, including areas that later became parts of Ray and Daviess Counties. They also founded Far West in Caldwell County as their main city in Missouri.

Once they had their own county, there was a time of peace. A Latter Day Saint newspaper, the Elders' Journal, said that "The Saints here are at perfect peace with all the surrounding inhabitants."

A Mormon leader named John Corrill remembered that "Friendship began to be restored between (the Mormons) and their neighbors... until the summer of 1838."

Why Did the Peace End in 1838?

In 1837, problems with a bank in the church's main city of Kirtland, Ohio, led to disagreements among leaders. The church then moved its headquarters from Kirtland to Far West, Missouri. More Mormons moved to Missouri, settling in new areas outside Caldwell County. These new settlements included Adam-ondi-Ahman in Daviess County and De Witt in Carroll County.

Many non-Mormon citizens saw these new settlements as breaking the earlier agreement. Mormons felt the agreement only stopped them from settling in Clay and Ray Counties, not Daviess or Carroll.

The earlier settlers worried that the growth of Mormon communities outside Caldwell County would affect their politics and economy. In Daviess County, where political parties were evenly matched, the Mormon population grew so much that they could decide election results.

New Groups and Tensions

Around this time, some Mormon leaders were removed from the church, including Oliver Cowdery and David Whitmer. These "dissenters" owned a lot of land in Caldwell County. They had bought much of this land for the church, and now who owned it was unclear. The dissenters threatened to sue the church.

Church leaders responded by strongly urging the dissenters to leave the county. Sidney Rigdon, a church leader, gave a speech known as the Salt Sermon. He said that the dissenters were like salt that had lost its flavor, and it was the duty of faithful members to cast them out.

At the same time, some Mormons, like Sampson Avard, started a secret group called the Danites. This group aimed to follow the church leaders no matter what, and to force the dissenters out of Caldwell County. Two days after Rigdon's speech, 80 important Mormons, including Hyrum Smith, signed a paper called the Danite Manifesto. This paper warned the dissenters to "depart or a more fatal calamity shall befall you." On June 19, the dissenters and their families fled to nearby counties. Their complaints made anti-Mormon feelings even stronger.

On July 4, Rigdon gave another speech. He said that Latter-day Saints would no longer be driven from their homes. He warned that if enemies came to drive them out again, "it shall be between us and them a war of extermination." Joseph Smith supported this speech.

The Election Day Fight at Gallatin

The "Election Day Battle at Gallatin" was a fight between Mormons and non-Mormons in Daviess County, Missouri, on August 6, 1838.

William Peniston, a candidate for the state legislature, spoke badly about the Mormons. He called them "horse-thieves and robbers" and told them not to vote. He warned that if Missourians let Mormons vote, they would "soon lose your suffrage" (their right to vote). About 200 non-Mormons gathered in Gallatin on election day to stop Mormons from voting.

When about thirty Latter Day Saints came to vote, a Missourian said that in Clay County, Mormons were not allowed to vote, "no more than negroes." Samuel Brown, a Mormon, said Peniston's words were false and said he intended to vote. This started a brawl.

During the fight, a Mormon named John Butler shouted, "Oh yes, you Danites, here is a job for us!" This rallied the Mormons, and they drove off their opponents.

Some Missourians left to get guns. The crowd broke up, and the Mormons went home.

This fight is often seen as the first serious violence of the war in Missouri.

Rumors spread that people had been killed on both sides, but Joseph Smith and others found these rumors were not true.

When Mormons heard a rumor that Judge Adam Black was gathering a mob, about one hundred armed Mormons, including Joseph Smith, surrounded Black's home. They asked if the rumor was true and demanded he sign a paper saying he was not part of any mob. Black refused at first, but after talking with Smith, he signed a paper saying he would not bother the Mormons if they did not bother him. Black later said he felt threatened by the armed men.

Mormons also visited Sheriff William Morgan and other important citizens in Daviess County. They also forced some of them to sign papers saying they were not involved with anti-Mormon groups.

At a meeting, Mormon and non-Mormon leaders agreed not to protect anyone who broke the law and to turn over offenders to the authorities. With peace seemingly restored, Smith's group returned to Caldwell County.

Judge Black and others filed complaints against Smith and the other Mormons involved. On September 7, Smith and Lyman Wight appeared before Judge Austin A. King. The judge found enough evidence to send them to a grand jury for minor charges.

Mormons Forced Out of De Witt

In the spring of 1838, Henry Root, a non-Mormon landowner, sold plots in the mostly empty town of De Witt to church leaders. De Witt was important because it was near where the Grand River and Missouri River met. Two Mormon leaders, George M. Hinkle and John Murdock, were sent to take over the town and start a new settlement.

On July 30, citizens of Carroll County met to discuss the Mormon settlement in De Witt. They voted on whether Mormons should be allowed to settle there. A large majority voted to expel the Mormons. A group sent to De Witt ordered the Latter-day Saints to leave. Hinkle and Murdock refused, saying they had a right as American citizens to live where they chose.

Anti-Mormon feelings in Carroll County grew stronger, and some people started to arm themselves. On August 19, 1838, a Mormon settler named Smith Humphrey reported that 100 armed men, led by Colonel William Claude Jones, held him prisoner for two hours. They threatened him and the Mormon community.

The reaction from other Missourians was mixed. While many saw Mormons negatively, some agreed that people should have the right to settle freely.

As tensions grew in Daviess County, other counties started to help Carroll County in forcing Mormons out. Groups in Saline, Howard, Jackson, Chariton, Ray, and other nearby counties formed committees to support the expulsion.

Some isolated Mormons in rural areas were also attacked. In Livingston County, armed men forced Asahel Lathrop from his home. They held his sick wife and children prisoner. After more than a week, armed Mormons helped Lathrop rescue his wife and two children. Lathrop's wife and the remaining children died soon after their rescue.

On September 20, 1838, about 150 armed men rode into De Witt. They demanded that the Mormons leave within ten days. Hinkle and other Mormon leaders said they would fight. They also asked Governor Boggs for help, saying the mob had threatened to kill them.

On October 1, the mob burned Smith Humphrey's home and stables. The people of De Witt sent Henry Root to ask Judge King and General Parks for help. Later that day, the Carroll County forces surrounded the town.

General Parks arrived with the Ray County militia on October 6, but the mob ignored his order to leave. When his own troops threatened to join the attackers, Parks had to retreat to Daviess County. He hoped the Governor would come to help. Parks wrote to his superior, General David Rice Atchison, that "a word from his Excellency would have more power to quell this affair than a regiment."

On October 9, A C Caldwell returned to De Witt. He reported that the Governor's response was that the "quarrel was between the Mormons and the mob" and that they should fight it out.

On October 11, Mormon leaders agreed to leave De Witt and move to Caldwell County.

On the first night of their journey out of Carroll County, two Mormon women died.

Events in Daviess County

General David Rice Atchison wrote to Governor Lilburn Boggs on October 16, 1838. He said that General Parks reported that men from Carroll County were heading to Daviess County. They planned to do the same thing there: drive Mormons out of Daviess County and possibly from Caldwell County. Atchison suggested that the Governor visit the area or issue a strong statement to restore peace. However, Boggs did not act and waited as events got worse.

Meanwhile, non-Mormons from Clinton, Platte, and other counties began to harass Mormons in Daviess County. They burned homes and stole property. Latter Day Saint families started to flee to Adam-ondi-Ahman for safety as winter approached. Joseph Smith, returning to Far West from De Witt, learned about the worsening situation from General Doniphan. Doniphan already had troops ready to prevent fighting in Daviess County. On Sunday, October 14, a small group of state militia arrived in Far West. They were under the command of Colonel William A. Dunn. Dunn, following Doniphan's orders, continued to Adam-ondi-Ahman. Doniphan told the Mormons that the Caldwell County militia could not legally go into Daviess County. He advised Mormons traveling there to go in small, unarmed groups. Ignoring this advice, Judge Higby, a Mormon judge in Caldwell County, called out the Caldwell militia. This militia was led by Colonel George M. Hinkle. Even though county officials could only legally act within their own county, this judge allowed Hinkle to defend Mormon settlements in Daviess County.

Colonel Hinkle and the Caldwell County militia were joined by members of the Danite group. On October 18, these Mormons marched armed in three groups to Daviess County. Lyman Wight and his group attacked Millport. David W. Patten attacked Gallatin. Seymour Brunson attacked Grindstone Fork. The Missourians and their families, outnumbered by the Mormons, fled to nearby counties.

After taking control of the Missourian settlements, the Mormons took property and burned stores and houses. The county seat, Gallatin, was almost completely destroyed. Only one shoe store was left untouched. Millport, Grindstone Fork, and Splawn's Ridge were also looted, and some houses were burned. The stolen goods were stored at the Mormon Bishop's storehouse in Diahman.

In the following days, Mormon groups, encouraged by Lyman Wight, drove Missourians from their farms. Their homes were also looted and burned. One witness said, "We could stand in our door and see houses burning every night for over two weeks... the Mormons completely gutted Daviess County."

The Missourians forced from their homes were not prepared, just like the Mormon refugees had been earlier.

Even Missourians who had been friendly to the Mormons were affected. Jacob Stollings, a merchant, had been generous in selling to Mormons on credit. But his store was looted and burned. Judge Josiah Morin and Samuel McBrier, who were considered friendly to Mormons, both fled Daviess County after being threatened. McBrier's house was among those burned.

When a Mormon group looted and burned the Taylor home, a young Mormon, Benjamin F Johnson, convinced his group to leave a horse for a pregnant Mrs. Taylor and her children to ride to safety. Because of his kindness, he was the only Mormon clearly identified as taking part in the burnings. After several non-Mormons told authorities that Johnson had tried to calm the Danites, he was allowed to escape instead of facing trial.

Many Latter Day Saints were very upset by these events. Mormon leader John Corrill wrote, "the love of pillage grew upon them very fast, for they plundered every kind of property they could get a hold of." Some Latter-day Saints claimed that some Missourians burned their own homes to blame the Mormons. However, most accounts from both Missourians and Mormons say that Mormons were responsible for the burnings. Evidence of stolen property found with Mormons also supports this. One historian estimates that Mormons burned about fifty homes or shops and forced one hundred non-Mormon families to leave. Millport, which was the largest city in the county at the time, never recovered and became a ghost town.

Local citizens were very angry about the actions of the Danites and other Mormon groups. Several Mormon homes near Millport were burned, and their residents were forced out into the snow. Agnes Smith, Joseph Smith's sister-in-law, was chased from her home with two small children when it was burned. With a child in each arm, she walked through an icy creek to safety in Adam-ondi-Ahman. Nathan Tanner reported that his militia group rescued another woman and three small children. Other Mormons, fearing similar revenge, gathered into Adam-ondi-Ahman for protection.

Marsh's Statement

Thomas B. Marsh, a leader in the church, and fellow leader Orson Hyde were worried by the events in Daviess County. On October 19, 1838, the day after Gallatin was burned, they left the church. On October 24, they gave sworn statements about the burning and looting in Daviess County. They also reported about the Danite group among the Mormons. They repeated a rumor that Danites planned to attack and burn Richmond and Liberty.

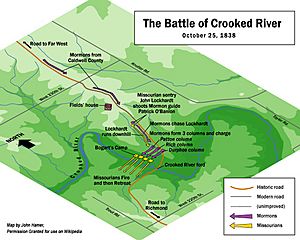

Battle of Crooked River

Fearing attack, many people in Ray County moved their families across the Missouri River for safety. A militia group, led by Samuel Bogart, was allowed by General Atchison to patrol an area between Ray and Caldwell Counties. This area was known as "Bunkham's Strip." Instead of staying in this strip, Bogart went into southern Caldwell County and started taking weapons from Mormons. A rumor reached Far West that a militia unit had taken Mormons prisoner. An armed group was quickly put together to rescue these prisoners and push the militia out of the county.

When the Mormons arrived, the state militia was camped along Crooked River, just south of Caldwell County. The Mormons split into three groups, led by David W. Patten, Charles C. Rich, and James Durphee. The Missouri Militia had a better position and fired first, but the Mormons kept advancing. The Militia broke ranks and fled across the river. Although Mormons won the battle, they had more casualties than the Militia. Only one militiaman, Moses Rowland, was killed. On the Mormon side, Gideon Carter was killed, and nine other Mormons were wounded, including Patten.

The Extermination Order

News of the battle spread quickly and caused panic in northwestern Missouri. Early reports, which were exaggerated, said that almost all of Bogart's company had been killed. Generals Atchison, Doniphan, and Parks decided they needed to call out the militia to "prevent further violence." This was explained in a letter to US Army Colonel R. B. Mason: "The citizens of Daviess, Carroll, and some other counties have raised mob after mob for the last two months for the purpose of driving a group of mormons from those counties and from the State."

While the state militia gathered, unofficial Missouri groups continued to act on their own. They drove Mormons inward to Far West and Adam-ondi-Ahman.

Meanwhile, exaggerated reports from the Battle of Crooked River reached Missouri's governor, Lilburn Boggs. Boggs already had strong negative feelings about the Mormons from when they both lived in Jackson County. Even though he had not stopped the illegal anti-Mormon siege of De Witt, he now called up 2,500 state militia members to stop what he saw as a Mormon uprising against the state. Possibly using Rigdon's July 4 speech about a "war of extermination," Boggs issued Missouri Executive Order 44, also known as the "Extermination Order," on October 27. This order stated that "the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace..." This Extermination Order was finally officially canceled on June 25, 1976, by Governor Christopher Samuel "Kit" Bond.

Haun's Mill Massacre

Anger against the Latter Day Saints had become very strong in the less populated counties north and east of Caldwell County. Mormon dissenters from Daviess County who had fled to Livingston County reportedly told the Livingston County militia that Mormons were gathering at Haun's Mill to attack Livingston County. One historian noted:

"The Daviess County men were very bitter against the Mormons... It did not matter whether or not the Mormons at [Haun's] mill had taken any part in the disturbance... it was enough that they were Mormons."

Even though the governor's "Extermination Order" had just been issued, it probably had not reached these men yet. Also, the order would not have allowed them to cross into Caldwell County to raid. None of the attackers later said the order was why they acted.

On October 29, a large group of about 250 men gathered and entered eastern Caldwell County. When these Missouri raiders approached the settlement on the afternoon of October 30, about 30 to 40 Latter Day Saint families were living or camped there. Despite an attempt by the Mormons to talk, the mob attacked.

Mormon women and children ran and hid in the nearby woods and homes. Mormon men and boys gathered to defend the settlement. They went into a blacksmith shop, hoping to use it as a makeshift fort. The mob showed no mercy. Most of the defenders in the blacksmith shop were killed or badly wounded.

In total, 17 Latter Day Saints were killed in what became known as the Haun's Mill Massacre. When survivors reached Far West, their reports of the brutal attack played a big part in the Mormons' decision to surrender.

None of the Missourians were ever punished for their part in the Haun's Mill Massacre.

Surrender at Far West

Most Mormons gathered in Far West and Adam-ondi-Ahman for safety. Major General Samuel D. Lucas marched the state militia to Far West and surrounded the Mormon headquarters.

Inside Far West, the mood was tense. Joseph Smith ordered Colonel George M. Hinkle, the head of the Mormon militia in Caldwell County, to meet with General Lucas to discuss terms. According to Hinkle, Smith wanted a peaceful agreement with the Missourians "on any terms short of battle."

Lucas's terms were very harsh. The Latter-day Saints had to give up their leaders for trial and surrender all their weapons. Every Mormon who had fought had to sell their property to pay for damages to Missourian property and for the militia's expenses. Finally, the Mormons who had fought had to leave the state. Colonel Hinkle said that the Latter Day Saints would help bring to justice Mormons who had broken the law. But he argued that the other terms were illegal.

Colonel Hinkle rode back to the church leaders in Far West and told them the terms. According to a Latter Day Saint witness, Reed Peck, when Smith was told that Mormons would have to leave the state, he replied that "he did not care" and would be glad to get out of the state anyway. Smith and the other leaders rode with Hinkle back to the Missouri militia camp. The militia immediately arrested Smith and the other leaders. Smith believed that Hinkle had betrayed him. But Hinkle said he was innocent and was just following Smith's orders.

Joseph Smith and the other arrested leaders were held overnight in General Lucas's camp, exposed to the weather.

Hyrum Smith, Brigham Young, and other leaders still in Far West warned the veterans of the Crooked River battle to flee.

Joseph Smith Jr. tried to negotiate with Lucas, but it was clear that Lucas would not change his conditions. At 8:00 AM, Joseph sent word to Far West to surrender.

Ebenezer Robinson described the scene at Far West: "General Clark made the following speech to the brethren on the public square: '... The orders of the governor to me were, that you should be exterminated, and not allowed to remain in the state, and had your leaders not been given up, and the terms of the treaty complied with, before this, you and your families would have been destroyed and your houses in ashes.'"

The Far West militia was marched out of the city and forced to give their weapons to General Lucas. Lucas's men were then allowed to search the city for weapons. Brigham Young said that once the militia was disarmed, Lucas's men were let loose on the city: "[T]hey commenced their ravages by plundering the citizens of their bedding, clothing, money, wearing apparel, and every thing of value they could lay their hands upon..."

Trials and Escape

Lucas held a quick trial for Joseph Smith and other Mormon leaders on November 1, the evening of the surrender.

The defendants, about 60 men including Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon, were then sent to a civil court in Richmond. This was under Judge Austin Augustus King. They faced serious charges like treason, murder, arson, burglary, robbery, and lying under oath. The court hearing began on November 12, 1838. After the hearing, most of the Mormon prisoners were released. However, Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Lyman Wight, Caleb Baldwin, Hyrum Smith, and Alexander McRae were held in the Liberty Jail in Liberty, Clay County. They were accused of serious crimes against the state.

During a transfer to another prison in the spring of 1839, Smith escaped. The exact details of his escape are not fully known. John Whitmer said that Smith bribed the guards.

It is also believed that Smith's imprisonment had become an embarrassment for Governor Boggs and other Missouri politicians. An escape might have been convenient for them.

Smith and the other Mormons resettled in Nauvoo, Illinois, starting in 1839.

People in Daviess County were very angry about Smith and the other leaders escaping.

What Happened After the War?

General Clark believed that the Governor's order was fulfilled when the Mormons agreed to leave the state the following spring. The militia was sent home in late November.

Missouri blamed the Mormons for the conflict. They forced the Latter-day Saints to sign over all their lands to pay for the state militia's expenses.

Mormon leaders asked the state government to cancel the order that they leave the state. But the government delayed the issue until after the Mormons had already left.

Since the Governor and government refused to help, and with most of their weapons taken, Mormons were almost defenseless against angry groups. Mormon residents were harassed and attacked by angry people who were no longer controlled by militia officers.

Mormons Move to Illinois

Having lost their property, the Mormons were given a few months to leave Missouri. Most refugees traveled east to Illinois, where people in the town of Quincy helped them. The people of Quincy were upset by how the Mormons had been treated in Missouri. One statement from the Quincy town council said: "Resolved: That the gov of Missouri, in refusing protection to this class of people when pressed upon by an heartless mob, and turning upon them a band of unprincipled Militia, with orders encouraging their extermination, has brought a lasting disgrace upon the state over which he presides."

Eventually, most of the Mormons gathered and founded a new city in Illinois, which they named Nauvoo.

Political Impact

When events in Daviess County made Missourians see the Mormon community as a violent threat, public opinion against Mormons grew stronger. Even militia commanders like Clark, Doniphan, and Atchison, who had some sympathy for the Mormons, came to believe that military action was the only way to control the situation.

Many people in Missouri felt that Governor Boggs had handled the situation poorly. They thought he failed to act earlier and then overreacted based on incomplete information.

The Missouri Argus newspaper wrote on December 20, 1838, that public opinion should not allow Mormons to be forced out of the state: "They cannot be driven beyond the limits of the state—that is certain. To do so, would be to act with extreme cruelty... The refinement, the charity of our age, will not brook it."

Even people who did not like the Mormons were shocked by Boggs's order and how the mobs treated the Mormons. One critic of the Mormons wrote: "Mormonism is a monstrous evil; and the only place where it ever did or ever could shine... is by the side of the Missouri mob."

Attempted Attack on Governor Boggs

On May 6, 1842, Boggs was shot at his home. Boggs survived, but Mormons were immediately suspected, especially Orrin Porter Rockwell, who was a close associate of Joseph Smith.

A sheriff found a gun at the scene. He thought the attacker fired at Boggs and dropped the gun because it kicked back hard. The gun had been stolen from a local shop. The shopkeeper identified "that hired man of Ward's" as the likely thief. The sheriff believed this man was Porter Rockwell. However, the sheriff could not catch Rockwell.

John C. Bennett, a former Mormon, claimed that Smith had offered money to anyone who would attack Boggs. He also said Smith admitted that Rockwell had done it.

Joseph Smith strongly denied Bennett's story. He thought Boggs, who was no longer governor but running for state senate, was attacked by a political rival. One historian notes that Governor Boggs was running against several violent men, any of whom could have done it. There was no special reason to suspect Rockwell. Other historians believe Rockwell was involved in the shooting.

Whatever the truth, Rockwell was arrested the next year. He was tried and found not guilty of the attempted murder. However, most people at the time still believed he was guilty. A grand jury could not find enough evidence to charge him.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra mormona de 1838 para niños

In Spanish: Guerra mormona de 1838 para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |