Murasaki Shikibu facts for kids

Murasaki Shikibu (born around 973) was a Japanese writer, poet, and a lady-in-waiting at the Imperial court during Japan's Heian period. She is famous for writing The Tale of Genji, which is thought to be one of the world's first novels. It was written in Japanese between the years 1000 and 1012.

"Murasaki Shikibu" was a nickname given to her at court. Her real name is not known for sure, but it might have been Fujiwara no Kaoruko.

During the Heian period, it was not common for women to learn Chinese, the language of the government. But Murasaki's father was a scholar, and she showed a great talent for learning. She became fluent in Chinese.

She married in her twenties and had a daughter. Sadly, her husband died after only two years of marriage. Around 1005, she was invited to the Imperial court to serve Empress Shōshi. She continued to write The Tale of Genji while at court, adding details about court life to her story. Scholars believe she died around the year 1014, but some think she may have lived until 1025.

Contents

Early Life

Murasaki Shikibu was born around the year 973 in Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto), Japan. She was part of the noble Fujiwara clan. The Fujiwara family was very powerful in politics. They often arranged for their daughters to marry into the emperor's family.

However, Murasaki's part of the family was not as powerful. Her family was known for its talented writers and poets. Her father, Fujiwara no Tametoki, was a respected scholar of Chinese literature and poetry.

Her Name and Family

In the Heian era, women's names were different from today. "Shikibu" refers to the Ministry of Ceremonials, where her father worked. The name "Murasaki," which means violet, might have come from a character in her book, The Tale of Genji.

Usually, children in noble families lived with their mothers. But Murasaki was different. After her mother died when she was young, she grew up in her father's house with her younger brother.

A Special Education

In Murasaki's time, only boys were taught Chinese to prepare for jobs in the government. Girls were not expected to learn it. But Murasaki was very clever.

In her diary, she wrote that she would listen to her brother's lessons in Chinese. She was so good at it that she understood parts that her brother found difficult. Her father, a well-educated man, would say, "What a pity she was not born a man!"

Besides Chinese, she also studied music, calligraphy (artistic writing), and Japanese poetry.

Marriage and Writing

Noblewomen in the Heian period lived quiet lives. They usually only spoke to male family members. Murasaki stayed in her father's home until her mid-twenties.

When her father became a governor in Echizen Province, she traveled with him. This was unusual for a noblewoman. Later, she returned to Kyoto and married her father's friend, Fujiwara no Nobutaka. He was much older than her and was well-known at court.

In 999, they had a daughter named Kenshi. But just two years later, her husband died during an epidemic. Murasaki was very sad. She wrote in her diary, "I felt depressed and confused... The thought of my continuing loneliness was quite unbearable."

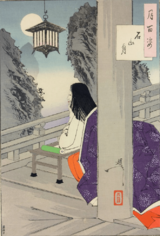

It was likely during this time of sadness that she began writing The Tale of Genji. A popular legend says that Murasaki went to the Ishiyama Temple. One night, while looking at the Moon over Lake Biwa, she was inspired to write her famous story. While this is a nice story, historians don't think it really happened that way.

As she wrote new chapters of Genji, she shared them with her friends. Her friends made copies and passed them on. Soon, her story became well-known, and she earned a reputation as a talented author.

Life at the Imperial Court

Around 1005, Murasaki was invited to become a lady-in-waiting for Empress Shōshi. This was probably because of her fame as a writer.

Life at the Heian court was focused on art and culture. Courtiers expressed their feelings through beautiful textiles, perfumes, poetry, and colorful clothing. Noblewomen had floor-length hair, wore white makeup, and blackened their teeth, which was considered beautiful at the time.

Rival Writers

The court was a place of competition. The powerful leader Fujiwara no Michinaga wanted his daughter, Empress Shōshi, to have a brilliant and cultured court. He gathered talented women writers to serve her, including Murasaki.

Another famous writer of the time was Sei Shōnagon. She had served another empress, Teishi. Sei Shōnagon was known for her witty and clever book, The Pillow Book. Murasaki and Sei Shōnagon had very different personalities. Shōnagon was outgoing, while Murasaki was quiet and thoughtful.

In her diary, Murasaki wrote that she found Sei Shōnagon to be a bit conceited. She said Shōnagon liked to show off her knowledge of Chinese characters in her writing.

The Lady of the Chronicles

Murasaki's knowledge of Chinese was very unusual for a woman. Empress Shōshi was interested in Chinese literature, so Murasaki secretly taught her. Because of this, Murasaki earned a nickname: "The Lady of the Chronicles." This name referred to the Chronicles of Japan, a famous history book written in Chinese.

Murasaki did not enjoy all parts of court life. She found it difficult sometimes and disliked the noisy parties. However, she had an important supporter in Fujiwara no Michinaga. He gave her the expensive paper and ink she needed to continue writing her long story.

The experiences she had at court are described in the later chapters of The Tale of Genji.

Later Life and Death

When Emperor Ichijō died in 1011, Empress Shōshi left the Imperial Palace. Murasaki likely went with her.

Murasaki may have died in 1014, when she was about 41 years old. Her father rushed back to Kyoto from his job in a faraway province that year, possibly because she had died. Other historians think she may have lived until 1025.

Her daughter, Kenshi, also became a well-known poet at the court, known as Daini no Sanmi.

Famous Works

Murasaki Shikibu is known for three main works: The Tale of Genji, The Diary of Lady Murasaki, and a collection of 128 poems called Poetic Memoirs. Her writing is very important because it helped shape the Japanese written language.

The Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji is Murasaki's most famous work. It is a very long novel, with 54 chapters and over 1,000 pages. It tells the story of a handsome and charming prince named Genji, also known as the "shining prince." The book follows his life, his friendships, and his search for love.

The story is not just a simple romance. It explores deep feelings about life, beauty, and sadness. A key theme is mono no aware, which means "the sorrow of human existence" or an awareness of how fragile life is.

The book was very popular, even in Murasaki's own time. Emperor Ichijō himself had it read to him. By 1021, all the chapters were finished, and people all over Japan wanted to read it.

Legacy

Murasaki Shikibu's work has been celebrated for over a thousand years. She is considered one of the greatest writers in Japanese history. Her work is so important that she is often compared to William Shakespeare for her impact on literature.

As early as the 12th century, her book was required reading for poets at the court. Soon after, artists began to create beautiful illustrated handscrolls of the story, called Genji Monogatari Emaki.

For centuries, Japanese artists have created paintings, woodblock prints, and other artworks based on The Tale of Genji. Murasaki herself became a popular subject for paintings. She is often shown at her desk at Ishiyama Temple, looking at the moon for inspiration.

Today, her legacy continues. In 2008, Kyoto held a year-long celebration for the 1000th anniversary of The Tale of Genji. Her picture and a scene from her novel appear on Japan's 2000 yen banknote. Her story has also inspired modern comics, known as manga, and films.

The Tale of Genji is still read by people all over the world. It shows the fascinating world of the Heian court and explores human feelings that are still relatable today.

Gallery

-

In The Tale of Genji, Murasaki described court life, as depicted in this exterior scene titled "Royal Outing", late 16th century by Tosa Mitsuyoshi.

-

Hiroshige ukiyo-e print (1852) shows an interior court scene from The Tale of Genji.

-

In this 1795 woodcut, Murasaki is shown in discussion with five male court poets.

See also

In Spanish: Murasaki Shikibu para niños

In Spanish: Murasaki Shikibu para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |