Operation Bernhard facts for kids

Operation Bernhard was a secret plan by Nazi Germany during World War II. Their goal was to fake British money, like pound notes. The first idea was to drop these fake notes over Britain. This was meant to cause a huge economic problem for the British economy.

The first part of this plan started in early 1940. It was called Unternehmen Andreas (Operation Andreas). A special team from the Nazi secret service, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), ran it. This team learned how to copy the special paper used for British money. They also made printing plates that looked almost exactly the same. Plus, they figured out the secret code for the serial numbers on each note. This first team stopped working in early 1942. This happened after its leader, Alfred Naujocks, had problems with his boss, Reinhard Heydrich.

The plan started again later in 1942. This time, the goal changed. The fake money would now be used to pay for German spy operations. Instead of a regular unit, prisoners from Nazi concentration camps were chosen. They were sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp to work. They worked under an SS officer named Bernhard Krüger. This group made British notes until mid-1945. Experts think they printed between £132.6 million and £300 million in fake money. By the time they stopped, they were also close to perfectly faking US dollars.

The fake money was used to pay for many things. For example, some was used to pay a Turkish spy named Elyesa Bazna. He was code-named Cicero. He gave German spies British secrets from the British ambassador in Ankara. Also, £100,000 from Operation Bernhard helped free the Italian leader Benito Mussolini. This happened during the Gran Sasso raid in September 1943.

In early 1945, the team of prisoners was moved. They went to Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in Austria. Then they moved to tunnels at Redl-Zipf, and finally to Ebensee concentration camp. The prisoners were supposed to be killed when they arrived. But a misunderstanding of an order saved them. Soon after, the American Army arrived and freed them. Much of the fake money was thrown into the Toplitz and Grundlsee lakes. But enough fake money got into circulation that the Bank of England had to stop printing old notes. They issued new designs after the war. This operation has been shown in TV shows and movies. These include the 1981 miniseries Private Schulz and the 2007 film The Counterfeiters.

Contents

How the Fake Money Plan Started

British Money Before the War

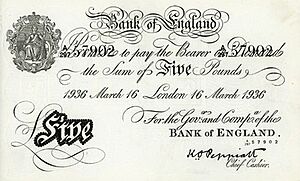

The designs for British paper money at the start of World War II were quite old. They had been used since 1855 with only small changes. The notes were made from white rag paper. They had black printing on one side. Each note showed an engraving of Britannia in the top left corner. This image was made by Daniel Maclise. The £5 note, also called the White Fiver, was about 7.7 inches by 4.7 inches. Other notes like the £10, £20, and £50 were slightly larger.

These notes had about 150 small marks. These marks were security features to spot fake money. People often thought these were just printing mistakes. The marks would change a little with each new batch of notes. Every note also had a special serial number and the signature of the Chief Cashier of the Bank of England. Before any notes were released, all their serial numbers were written down. This helped the bank keep track of its money.

A watermark was also part of every note. This watermark was different for each value of money. It also changed based on the serial number. According to John Keyworth from the Bank of England Museum, the bank was "a little complacent" about its notes. This was because no one had ever successfully faked them before. He said the notes were "very simple" in terms of technology.

The Idea for the Plan

On September 18, 1939, Arthur Nebe had an idea. He was the head of the main criminal police department in Nazi Germany. He suggested using known criminals who were good at faking money. They would forge British paper money. The plan was to make £30 billion in fake notes. Then, they would drop them over Britain. This would cause Britain's economy to crash. It would also make the British pound lose its status as a world currency.

Nebe's boss, Reinhard Heydrich, liked the idea. But he wasn't sure about using police records to find the right people. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, called it a "grotesque plan." But he still thought it had some potential. The main person against the plan was Walther Funk. He was the Minister for Economic Affairs. He said it would break international laws. But Adolf Hitler, the German leader, gave the final approval for the plan to go ahead.

Even though the discussion was supposed to be secret, news got out. In November 1939, Michael Palairet, Britain's ambassador to Greece, met a Russian person. This person told him all about the secret plan. The plan was called "Offensive against Sterling and Destruction of its Position as World Currency." Palairet told London about this. London then warned the US Treasury and the Bank of England. The Bank of England thought their security was good enough. But in 1940, they released a new blue £1 note. This note had a metal security thread inside the paper. In 1943, they also stopped allowing pound notes to be brought into the country. They stopped making new £5 notes. They also warned people about fake money.

Operation Andreas: The First Try

After Hitler said yes, Heydrich started a team to make fake money. It was called Unternehmen Andreas (Operation Andreas). Heydrich's order said the goal was to "destroy the British currency."

In early 1940, the fake money unit started in Berlin. It was part of the technical department of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD). Alfred Naujocks, an SS major, was in charge. His technical director, Albert Langer, managed the daily work. Langer was a mathematician and a code-breaker. They split the job into three parts. First, make paper that was exactly the same. Second, make printing plates that matched the British notes. Third, copy the British serial number system.

The Germans decided to focus on the £5 notes. These were the most common. Samples of British notes were sent to colleges for study. They found the paper was made of rags with no added wood pulp. Naujocks and Langer realized they had to make the paper by hand. At first, the fake paper looked different in color. The Germans had used new rags. After trying different things, they used rags that had been used by local factories. These rags were cleaned before being made into paper. Then, the colors of the fake and real notes matched.

When the first paper samples were made, they looked real in normal light. But under ultraviolet light, they looked dull compared to the real ones. Langer figured out it was because of the chemicals in the water used for the paper and ink. He copied the chemical balance of British water. This made the colors match perfectly.

To crack the serial number code, Langer worked with banking experts. They looked at records of money from the past 20 years. This helped them copy the correct order. No records were kept by Operation Andreas. So, we don't know exactly how they figured out the sequences. Historian Peter Bower thinks they might have used cryptanalysis techniques. German engravers had a hard time copying the image of Britannia. They called her "Bloody Britannia" because she was so difficult. After seven months, they thought they had a perfect copy. But Kenworthy says the eyes of the figure are still wrong.

By late 1940, Naujocks was removed from his job. He had fallen out of favor with Heydrich. The fake money unit continued under Langer. It closed down in early 1942 when Langer left. He later said that in 18 months, they made about £3 million in fake notes. Historian Anthony Pirie says the number was £500,000. Most of the money made in Operation Andreas was never used.

The Plan Under Krüger

In July 1942, the plan changed goals. Heinrich Himmler, a top SS leader, started the operation again. The first plan was to crash the British economy. But Himmler's new idea was to use the fake money to pay for German spy operations. The security services Himmler controlled didn't have much money. So, the fake funds helped fill these money gaps.

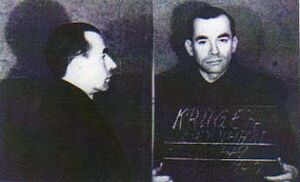

SS Major Bernhard Krüger took over from Naujocks. He found the copper printing plates and machines from the old Operation Andreas office. Some of the wire screens for watermarks were bent. Krüger was told to use Jewish prisoners from Nazi concentration camps. He set up his unit in blocks 18 and 19 at Sachsenhausen concentration camp. These blocks were separated from the rest of the camp by extra barbed wire. Special guards were assigned to them.

Krüger visited other concentration camps to find the right people. He mainly chose prisoners who were good at drawing, engraving, printing, and banking. In September 1942, the first 26 prisoners for Operation Bernhard arrived at Sachsenhausen. Another 80 arrived in December. When Krüger met them, he spoke to them politely. This was unusual, as Nazis usually spoke to Jewish prisoners in a rude way. Several prisoners later said Krüger interviewed them. They said he treated them with good manners. He also gave them cigarettes, newspapers, extra food, and a radio. Prisoners had a ping pong table and played with guards. They also put on plays for guards and other prisoners. Krüger even provided musicians for the shows.

The printing machines arrived in December. About 12,000 sheets of banknote paper started arriving each month. This paper was big enough to print four notes on each sheet. Making fake notes began in January 1943. It took a year to get back to the same level of production as Operation Andreas.

Each part of the process was led by one of the prisoners. Oscar Stein, a former office manager, ran the daily work. Two twelve-hour shifts kept production going all the time. About 140 prisoners worked. The printed sheets, with four notes each, were dried and cut. The edges were made rough to look like real British notes. The operation was busiest between mid-1943 and mid-1944. They made about 65,000 notes a month using six printing presses.

To make the notes look old, 40 to 50 prisoners stood in two lines. They passed the notes among themselves. This helped the notes get dirt, sweat, and general wear. Some prisoners would fold and unfold the notes. Others would pin the corners. This copied how bank clerks would hold bundles of notes. British names and addresses were written on the back of some notes. Numbers were written on the front. This was how bank tellers marked the value of a bundle.

They had four grades for the quality of the notes. Grade 1 was the best. These were used in neutral countries and by Nazi spies. Grade 2 notes were used to pay people who helped the Nazis. Grade 3 notes might be dropped over Britain. Grade 4 notes were too flawed and were destroyed.

The Nazi leaders were very happy with the results. Twelve prisoners, including three Jewish men, received the War Merit Medal. Six of the guards received a medal too.

In May 1944, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, a high-ranking SS officer, ordered a new task. The fake money unit was to start making fake US dollars. The artwork on dollar notes was more complex than British money. This caused problems for the forgers. Other challenges included the paper, which had tiny silk threads. Also, the special printing process made small ridges on the paper.

The prisoners realized something important. If they perfectly faked the dollars, their special work would end. This meant their lives would no longer be safe. So, they slowed down their progress as much as they could. The journalist Lawrence Malkin wrote that the prisoners felt Krüger quietly approved of this. Krüger himself would be sent to the front lines if Operation Bernhard ended. In August 1944, Salomon Smolianoff, a known forger, joined the team. He helped with faking US dollars and checking the quality of pound notes. The Jewish prisoners complained about working with a criminal. So, Krüger gave Smolianoff his own room to sleep in.

By late 1944, the prisoners had faked the back of the dollar note. By January 1945, they had faked the front. They made 20 samples of the $100 note. They didn't have the serial numbers yet. These were still being studied. Himmler and banking experts saw the samples. The engraving and printing were excellent. But the paper was not as good as real dollar notes.

The End of the War

Between late February and early March 1945, the Allied armies were getting closer. All note production at Sachsenhausen stopped. The equipment and supplies were packed up. The prisoners were moved to the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in Austria. They arrived on March 12. Soon after, Krüger arranged another move. They went to the Redl-Zipf tunnels to start production again. But the order to restart was quickly canceled. The prisoners were told to destroy the money cases they had. What wasn't burned was loaded onto trucks. The printing equipment was also loaded. Then, they were all sunk in the Toplitz and Grundlsee lakes.

In early May, Operation Bernhard officially ended. The prisoners were moved from the caves to the nearby Ebensee concentration camp. They were divided into three groups. A truck was supposed to take them to the camp. An order had been given to kill the prisoners. But only once they were all together at Ebensee. The truck delivered the first two groups to the camp. These men were kept separate from other prisoners. On the third trip, the truck broke down. The last group of prisoners had to walk to the camp. This took two days. Because the order said they had to be killed together, the first two groups were kept safe. They waited for their friends.

Because of the delay and the approaching Allied army, the first two groups were released. This happened on May 5. They joined the general camp population, and their SS guards ran away. That afternoon, the third group arrived at the camp. When their guards learned what happened to the first two groups, they also released their prisoners and fled. The American army arrived the next day and freed the camp.

Estimates vary on how much money was printed. It ranges from £132,610,945 (with £10,368,445 sent to the main Nazi office) up to £300 million (with £125 million being usable notes).

What Happened After and Its Impact

Krüger hid at his home until November 1946. Then he turned himself in to the British authorities. Faking an enemy's money was not a war crime. So, he faced no charges. He was held until early 1947. Then he was given to the French. They tried to get him to fake passports for them, but he refused. He was released in November 1948. He went through a process to clear his name from Nazi ties. The prisoners he saved helped by giving statements. He later worked for the Hahnemühle paper company.

Schwend, one of the money launderers, became very rich from Operation Bernhard. American forces caught him in June 1945. They tried to use him to help set up a spy network in Germany. But he was caught trying to cheat the network. He then fled to Peru. He sometimes worked as a spy for Peru. But he was arrested for smuggling money and selling state secrets. After two years in prison, he was sent back to West Germany. He was tried for a wartime murder in 1979. He received a suspended sentence for manslaughter.

Lake Toplitz has been searched many times. In 1958, an expedition found several boxes of the fake money. They also found a book with the Bank of England's numbering system. In 1963, a diver died in the lake. After this, the Austrian government searched the lake for a month. They found more boxes of notes. In 1989, a zoologist named Hans Fricke took Krüger in a mini-submarine. They explored the lake bottom. In 2000, a special submarine used to search the RMS Titanic wreck was used. It surveyed the lake floor. Several boxes of notes were found. Adolf Burger, a former prisoner from the operation, was there to see it.

One bank official said the fake notes were "the most dangerous ever seen." The watermark was the best way to spot them. About £15–20 million in fake notes were circulating after the war. Because so much fake money was out there, the Bank of England stopped releasing all notes of £10 and higher in April 1943. In February 1957, a new £5 banknote was issued. This blue note was printed on both sides. It used "subtle colour changes and detailed machine engraving" for security. Other notes were also brought back later.

A small group from the British Army's Jewish Brigade got some fake pounds. They got them from Jaacov Levy, one of Schwend's agents. The fake notes were used to buy equipment. They also helped bring people who had lost their homes to Palestine. This was done against the British blockade of the area.

Several prisoners have written books about their experiences. These include Falskmynter i blokk 19 by Moritz Nachtstern in 1949. Also, Des Teufels Werkstatt by Adolf Burger in 1983. Both books have been translated into English. Many other books have also been written about Operation Bernhard.

Operation Bernhard is also mentioned in Frederick Forsyth's 1972 novel The Odessa File.

In 1981, Private Schulz was shown on the BBC. It was a comedy-drama that told a fictional version of Operation Bernhard. It starred Michael Elphick and Ian Richardson. In 2007, Burger's book was used for a film called The Counterfeiters. This movie tells the story of Salomon Sorowitsch. This character is loosely based on Smolianoff and Burger. The film won an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

The Bank of England usually exchanges all old notes for new money. But they do not exchange fake money. However, fake notes from Operation Bernhard have been sold at auctions. They often sell for more than their original value. Examples of these notes are in the museum of the National Bank of Belgium and the Bank of England Museum. The International Spy Museum has an example of a printing plate from Operation Bernhard.

See Also

- Superdollars – high-quality fake dollars that might come from another country.

- Number Nine Research Laboratory – where the Imperial Japanese Army faked Chinese money.

- Opération Persil – French money manipulation with fake money in Guinea.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |