Operation Black Buck facts for kids

Operation Black Buck was a series of seven super long-distance bombing missions flown by the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the 1982 Falklands War. These missions used Vulcan bombers from RAF Waddington, flying against Argentine positions in the Falkland Islands. Five of these missions successfully attacked their targets. The main goal was to hit Port Stanley Airport and its defenses. These raids were incredibly long, covering almost 6,600 nautical miles (12,200 km) and lasting 16 hours for a round trip. At the time, they were the longest bombing raids ever flown.

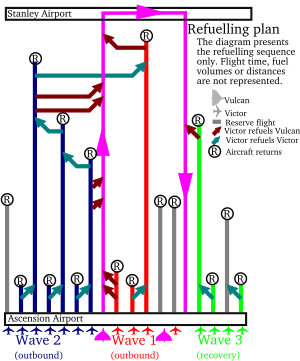

The Black Buck raids started from RAF Ascension Island, which is near the Equator. The Vulcan bomber was built for shorter missions in Europe, so it needed to refuel many times in the air to reach the Falklands. The RAF's tanker planes, mostly Handley Page Victor bombers, also needed to refuel in the air. This meant that up to eleven tankers were needed for just two Vulcans (one main bomber and one backup). It was a huge challenge to get all these planes to use the same runway and refuel each other in the sky.

The Vulcans carried either twenty-one 1,000-pound (450 kg) bombs inside or two to four Shrike anti-radar missiles on their wings. Three of the five successful Black Buck raids targeted Stanley Airfield's runway and buildings. The other two missions used Shrike missiles to attack a large AN/TPS-43 radar used by Argentina near Port Stanley. The Shrikes hit two smaller radar systems, causing some injuries to Argentine crews. In one mission, a Vulcan almost crashed when its refueling system broke, forcing it to land in Brazil.

The raids caused only minor damage to the runway, and the radar damage was quickly fixed. One bomb made a crater on the runway, making it hard for fast jets to use. However, Argentine ground crews fixed the runway within 24 hours, making it usable for C-130 Hercules transport planes. The British knew the runway was still being used. Some people think the RAF did these raids to show their importance in the war, especially since their funding had been cut in the late 1970s.

Contents

Why the Missions Happened

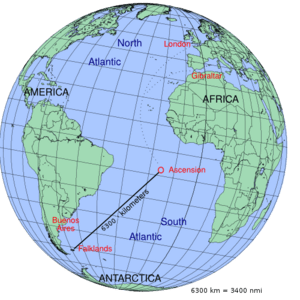

In the early 1980s, Britain's military was mostly focused on the Cold War with the Soviet Union. But they also looked at other possible conflict areas, like the Falkland Islands. Most experts thought the islands would be impossible to defend. The closest airfield they could use was on Ascension Island, a British territory far away in the South Atlantic. This island had one long runway, but it was 3,700 nautical miles (6,850 km) from the UK and 6,300 nautical miles (11,670 km) from the Falklands. The RAF didn't think they could operate in the South Atlantic without planes that could fly such long distances. So, the Royal Navy and British Army were expected to handle any operations there, with the RAF only providing support.

In March 1982, Britain started getting warnings that Argentina might do something in the South Atlantic. The RAF began to see if their Avro Vulcan bombers could fly long-range missions using aerial refuelling (refueling in the air). In 1961, a Vulcan had flown non-stop from the UK to Australia, which was even further. But that trip had fuel tankers waiting along the way, which wouldn't be possible from Ascension. At this point, they were just figuring out if it was possible, not what they would attack.

After Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands on April 2, 1982, the British government decided to take them back.

Victor Tanker Planes

Long-distance flights depended completely on the RAF's Handley Page Victor K2 tanker planes. Originally, 34 Victors were built as bombers, but 24 were later changed into tankers. By April 1982, only 23 were left. These were the only tankers Britain had at the time.

The tanker crews were very good at their job. They often refueled fighter jets that were sent to check on Soviet bombers entering British airspace. However, flying long distances over the South Atlantic meant they needed better navigation equipment.

The first five Victor tankers arrived at Ascension Island on April 18. More followed, bringing the total to fourteen. Each tanker was refueled by another Victor before leaving UK airspace. While the Victors were at Ascension, US Air Force KC-135 tankers helped with their usual refueling missions in the air.

The RAF first used Victor planes for scouting missions around South Georgia Island to help with Operation Paraquet, which was about taking back South Georgia. These missions showed that the Victor tanker fleet could support operations far away in the South Atlantic.

Vulcan Bombers

The Vulcan was the last of Britain's V bombers still used for bombing. By March 1982, only three squadrons were left, and they were all set to be shut down by July 1982. They were based in the UK and used for nuclear missions. They hadn't practiced air refueling or dropping regular bombs for years.

On April 11, Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward, who commanded the British aircraft carrier group heading south, asked for ideas on what targets to attack in the Falklands. This made the RAF think about using Vulcans for attacks. Ideas to attack airfields or ports on the Argentine mainland were dropped because they could cause political problems and might not be very effective. The head of the RAF, Air Chief Marshal Sir Michael Beetham, thought that just the threat of Vulcans would make Argentina keep their fighter jets in northern Argentina.

Everyone started focusing on a raid on Port Stanley Airport. There was a debate about whether it would be worth the effort. Beetham first suggested one Vulcan dropping seven 1,000-pound bombs. This small bomb load would mean less refueling. But tests showed that seven bombs wouldn't be enough. A full load of twenty-one bombs, however, had a 90% chance of making one crater on the runway and a 75% chance of making two. An attack was also expected to damage parking areas and nearby planes. To avoid anti-aircraft guns and surface-to-air missiles, the raids would happen at night, ideally in bad weather.

The military leaders thought the operation was possible and had a good chance of success. But civilian officials in the government were not so sure. There were also political issues with using Ascension Island for attacks, as it was technically a US Air Force base. The US government was asked and said they had no problem. The government gave permission for the operation, code-named Black Buck, on April 27.

The most debated part of the plan was using Sea Harriers from Woodward's fleet. One reason to use Vulcans was to save the Sea Harriers for defending the navy ships. But the plan needed Sea Harriers to fly a photo mission over the airfield in daylight to see the damage. If they had to risk the Harriers, then it might be better to just use them for the attack instead. Woodward was told on April 29 that the Black Buck raid would happen at 7:00 AM, and he needed to arrange the photo mission right after. Woodward replied that if the photo mission was so important, then Black Buck should be canceled. The next day, he was told Black Buck was approved, and the photo mission was needed not just to check damage, but also to prove Argentina's claims of random bombing were false.

Only Vulcans with the powerful Bristol Olympus 301 engines were chosen. Six planes were picked, but one wasn't used. Five crews were chosen. An air-to-air refueling instructor was added to each Vulcan crew to supervise the refueling.

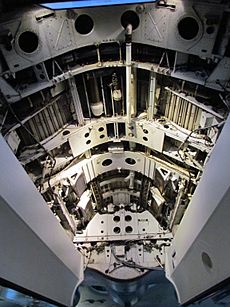

One of the hardest jobs was getting the air refueling system working again, as it had been sealed off. This involved finding and replacing special valves. Five planes were also fitted with a modern navigation system. AN/ALQ-101 electronic countermeasure pods (which jam enemy radar) from other planes were attached to the Vulcans' wings. The bottom of the planes were painted Dark Sea Grey.

Even though Vulcans could carry regular bombs, they hadn't done so in a long time. To carry twenty-one bombs, a Vulcan needed three bomb racks, each holding seven bombs. A special control panel, called a "90-way," released the bombs. None of the Vulcans had these bomb racks or the "90-way" panels. They found the panels in storage, but finding enough bomb racks was harder. Someone remembered some had been sold to a scrapyard, and they were brought back! Finding enough bombs was also tough. Training for conventional bombing and air refueling happened from April 14 to 17, mostly at night over the Atlantic Ocean.

The first two Vulcans left Waddington on April 29 and arrived at Ascension nine hours later after being refueled twice. Two more Vulcans arrived later in May.

Missions

| Mission | Target | Date | Primary Vulcan | Reserve Vulcan | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Buck 1 | Port Stanley Airport runway | 30 April–1 May | XM598 (Reeve) | XM607 (Withers) | Performed; primary aircraft had cabin pressure failure, replaced by reserve. | |

| Black Buck 2 | Port Stanley Airport runway | 3–4 May | XM607 (Reeve) | XM598 (Montgomery) | Performed. | |

| Black Buck 3 | Port Stanley Airport runway | 13 May | XM607 | XM612 | Cancelled before takeoff due to bad weather. | |

| Black Buck 4 | Anti-aircraft radar | 28 May | XM597 (McDougall) | XM598 (Montgomery) | Cancelled 5 hours into flight due to a tanker problem. | |

| Black Buck 5 | Anti-aircraft radar | 31 May | XM597 (McDougall) | XM598 (Montgomery) | Performed. | |

| Black Buck 6 | Anti-aircraft radar | 3 June | XM597 (McDougall) | XM598 (Montgomery) | Performed; primary aircraft forced to land in Brazil due to broken refueling probe. | |

| Black Buck 7 | Port Stanley Airport stores and aircraft | 12 June | XM607 (Withers) | XM598 (Montgomery) | Performed. |

Black Buck One

The first surprise attack on the islands happened on April 30 – May 1. It was the first major British attack against Argentine forces in the Falklands. The target was the main runway at Port Stanley Airport. The bomber carried twenty-one 1,000-pound bombs. The plan was to fly across the runway at an angle, dropping bombs from 10,000 feet (3,000 m) so at least one would hit the runway. The Vulcan's fuel tanks held 9,200 imperial gallons (41,800 L) of fuel. To refuel the single Vulcan, eleven Victor tankers were needed. This was the longest bombing mission ever tried at the time.

The eleven Victors and two Vulcans started taking off from Ascension Island at 11:50 PM, one minute apart. The Vulcans were very heavy with all their bombs and fuel. Their engines had to run at 103% power to get them off the ground in the warm Ascension air. Soon after takeoff, the main Vulcan, flown by John Reeve, had a problem: a window seal broke, so the cabin couldn't be pressurized. He had to return to Ascension. The Vulcan couldn't dump fuel, so it was too heavy to land right away. The crew had to stay in the cold, noisy cabin until enough fuel was used. Martin Withers took over as the main Vulcan pilot. Twenty minutes later, one of the Victor tankers also had to return due to a faulty refueling hose.

After the second refueling, only three planes were left: Withers's Vulcan, a Victor flown by Bob Tuxford, and another Victor flown by Steve Biglands. Because of the high fuel use and refueling problems, two Victors had to fly further south than planned, reducing their own fuel reserves. During the last refueling, they flew into a bad thunderstorm, and Biglands's refueling probe broke.

Tuxford was supposed to return after this refueling, but now he had to take Biglands's place. He realized he didn't have enough fuel to get back to Ascension. So, Tuxford had to do the final refueling. Withers received 7,000 pounds (3,200 kg) less fuel than expected. This meant he would have less fuel for the return refueling.

Now alone, Withers flew towards the Falklands. He flew low, at 300 feet (90 m), before climbing to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) for the bomb run, 40 miles (64 km) from the target. To confirm their position and avoid hitting civilians, they used their radar to lock onto Mount Usborne, a peak west of Stanley. Then the automatic bombing system took over. Withers made the final approach at 10,000 feet (3,000 m), flying at 330 knots (610 km/h). The Vulcan's electronic jamming systems defeated the Argentine radar controlling their anti-aircraft guns. All twenty-one bombs were dropped. Once they were all gone, Withers turned the Vulcan sharply left, pulling twice the force of gravity on the crew.

Withers climbed away from the airfield and headed north to meet a Victor tanker off the coast of Brazil. As they passed the British Task Force, the crew sent the code word "superfuse," meaning a successful attack, at 7:46 AM. Their journey continued within range of South America to meet a Victor flown by Barry Neal. Meanwhile, Tuxford, who had kept radio silence, heard the "superfuse" signal and called Ascension for help. Another Victor flew out to meet him and refueled Tuxford's plane, allowing him to return to Ascension 14 hours and 5 minutes after he left. With the help of a Nimrod reconnaissance plane, Withers met Neal, and all three planes returned safely to Ascension. Withers landed at 2:52 PM.

News of the bombing raid was reported on the BBC World Service before the Vulcan or the last tanker even arrived back at Ascension. The bombing is thought to have killed three Argentine soldiers at the airport and injured several more. One bomb exploded on the runway, making a large crater that was hard to fix. Other bombs caused minor damage to planes and equipment. The shortened runway could still be used.

Later that morning, twelve Sea Harriers from the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes attacked targets on East Falkland. Nine of them hit Port Stanley Airport, dropping 27 bombs. The bombs set a fuel stockpile on fire and might have slightly damaged the runway. One Sea Harrier was hit by an anti-aircraft round but managed to return to Hermes and was quickly repaired.

The other three Sea Harriers attacked the airfield at Goose Green with cluster bombs. This destroyed one Pucará plane and badly damaged two others. The pilot of the destroyed plane and five maintenance workers were killed. The damaged planes never flew again. The British planes faced no opposition and returned safely to Hermes.

For their bravery, Withers was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, and his crew were mentioned in official reports. Tuxford received the Air Force Cross, and his crew also received awards.

Black Buck Two

On the night of May 3–4, a Vulcan flown by John Reeve and his crew flew a mission almost exactly like the first one. This time, a Vulcan piloted by Alastair Montgomery was the backup but wasn't needed. Like Black Buck One, the plane flew low for the last 200 nautical miles (370 km) to Port Stanley, then climbed to 16,000 feet (4,900 m) for the bomb run. This was to avoid the now-alert Argentine anti-aircraft defenses, especially their Roland missiles. Because of the higher altitude, all the bombs missed the runway. This wasn't known for several days because bad weather prevented photo missions. Argentine sources say two Argentine soldiers were wounded. The craters near the western end of the runway stopped Argentine engineers from making it long enough for high-performance combat aircraft. But the runway was still used by Hercules and light transport planes, allowing Argentina to fly in important supplies and evacuate wounded soldiers.

Black Buck Three

After Black Buck Two, there was a break in Vulcan missions because the tankers were needed to help Nimrod planes hunt submarines. Each Nimrod mission to protect the navy needed 18 tanker flights. The two Vulcans returned to the UK on May 7, but one came back to Ascension on May 15 to be the main plane for Black Buck Three. Another Vulcan was the backup. Black Buck Three was planned for May 16 but was canceled before takeoff because of strong headwinds. The two Vulcans returned to the UK on May 20 and 23.

Black Buck Four

Black Buck Four was supposed to be the first mission using American-supplied Shrike anti-radar missiles. These missiles were attached to the Vulcans using special pylons under the wings. Vulcans had never used these weapons before, but they were quickly fitted and tested in just ten days. Vulcans with Shrikes could carry an extra 16,000 pounds (7,300 kg) of fuel in bomb bay tanks. This made their range longer and meant they needed fewer refuelings on the way to the Falklands.

The main plane was a Vulcan flown by Neil McDougall, which arrived at Ascension on May 27. Montgomery flew the backup plane. The mission was planned for May 28 but was canceled about five hours after takeoff. One of the supporting Victor refueling planes had a problem with its refueling hose, so the mission had to be called back.

Black Buck Five

Black Buck Five was flown by McDougall, with Montgomery as the backup. This was the first successful anti-radar mission using Shrike missiles. The main target was a large AN/TPS-43 radar that the Argentine Air Force had set up in April to guard the airspace around the Falkland Islands. This radar gave Argentina warnings, allowing them to hide mobile Exocet missile launchers. It also warned Argentine Hercules transports, so they could keep using the runway at Stanley. An attack on the radar with Shrike missiles would only work if the radar stayed on until it was hit. So, a Sea Harrier raid was timed to happen at the same time to force the Argentines to turn on the radar. At 8:45 AM, two Shrikes were fired at it. The first missile hit 10 to 15 yards (9 to 14 m) from the target, causing minor damage but not disabling the radar. The second missile missed by more.

Black Buck Six

Black Buck Six was flown on June 3 by McDougall. His Vulcan now had four Shrike missiles instead of two. Montgomery again flew the backup plane. McDougall flew around the target for 40 minutes, trying to hit the main AN/TPS-43 radar, but it wasn't turned on. Finally, the crew fired two of the four Shrikes. These destroyed a Skyguard radar used for anti-aircraft guns, killing four radar operators.

On its way back, McDougall's plane had to land in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, because its in-flight refueling probe broke. One of the missiles he was carrying was dropped into the ocean to reduce drag, but the other got stuck on the wing and couldn't be released. Secret documents were thrown into the sea through the crew hatch, and a "Mayday" signal was sent. Two Brazilian Air Force fighter jets intercepted the Vulcan. The plane was allowed to land at Galeão Airport with less than 2,000 pounds (900 kg) of fuel left, not enough to fly another circle around the airport.

This was a tricky international situation because it showed that the United States had given Britain Shrike missiles. British diplomats worked to get the Vulcan and its crew released. A deal was made on June 4: they would be released in exchange for spare parts for helicopters. Brazil was under pressure from Argentina, and the US helped keep the Shrike missile's secrets. The crew and plane were allowed to fly to Ascension on June 10. A new refueling probe was fitted there, and the plane flew back to the UK on June 13. The remaining Shrike missile stayed in Brazil.

Black Buck Seven

The last Black Buck mission was flown on June 12 by Withers and his crew. Montgomery again flew the backup plane. This time, the mission targeted Argentine troop positions and buildings around the airport, not the runway. The bombs were accidentally set to explode on impact. The war was almost over, and the plan had been for the bombs to explode in the air to destroy planes and supplies without damaging the runway. This was because the RAF would soon need the runway for their Phantom jets after the Falkland Islands were taken back. In the end, all 21 bombs missed their intended targets. The Argentine ground forces surrendered two days later.

Impact of the Missions

The military impact of Black Buck is still debated. Some experts say it was "minimal." The runway continued to be used by Argentine C-130 Hercules transport planes until the end of the war. However, after May 1, fewer supplies and troops were delivered, and early flights were stopped after May 4 because Black Buck missions happened in the early morning. The British knew that Hercules flights were still using the airfield and tried to stop them, which led to a Hercules being shot down on June 1. Some question whether targeting Stanley airport was worth it, given its small impact on the war's final outcome.

The plan for the raid was to drop bombs across the runway at a 35-degree angle, hoping to put at least one or two bombs on it. The main goal was to stop fast jets from using the runway. In this way, the raid was successful, as the runway repairs were not perfect, and there were several near accidents later. The fact that British forces could get past Argentine air defenses and attack the airfield had the desired effect: it stopped Argentina from risking their fast jets and the equipment needed to operate them on the islands, as they could be destroyed on the ground. Admiral Woodward thought it was very important to keep fast jets from using Port Stanley to reduce the threat to British aircraft carriers. Starting on May 1, the Royal Navy attacked Port Stanley with Sea Harriers and naval gunfire to slow down Argentine repair efforts. The Argentines would cover the runway with piles of earth during the day, which might have made British intelligence think repairs were still ongoing, misleading them about the airfield's condition and the success of their raids.

Commander Sharkey Ward, who commanded a Sea Harrier squadron and protected Black Buck One from fighter attacks, was very critical of Operation Black Buck. He calculated that the fuel used for Black Buck One to drop 21 bombs (which he estimated at 400,000 imperial gallons (1,800,000 L) costing £3.3 million) could have allowed Sea Harriers to fly 785 missions and drop 2,357 bombs. Ward called the claim that the raids made Argentina fear attacks on the mainland "RAF propaganda." He said:

Propaganda was, of course, used later to try to justify these missions: "The Mirage IIIs were redrawn from Southern Argentina to Buenos Aires to add to the defences there following the Vulcan raids on the islands." Apparently, the logic behind this statement was that if the Vulcan could hit Port Stanley, the [sic] Buenos Aires was well within range as well and was vulnerable to similar attacks. I never went along with that baloney. A lone Vulcan or two running into attack Buenos Aires without fighter support would have been shot to hell in quick time.

There is no proof that Mirage IIIs were moved from southern Argentina to protect Buenos Aires. On April 29, Argentine radars detected a possible British air strike, and planes were moved, but they still stayed in southern Argentina.

The British wanted to make the Argentine forces believe that a sea invasion of Port Stanley was about to happen. Admiral Woodward saw Black Buck One as an important part of this plan, along with naval attacks and tricks. The author of Vulcan 607, Rowland White, claimed that Vice Admiral Juan Lombardo was led to believe that Black Buck One was the start of a full British landing. Because of this, he ordered Rear Admiral Gualter Allara, the commander of the Argentine Sea Fleet, to attack the British fleet immediately. This attack involved the light cruiser ARA General Belgrano to the south and the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo to the north. On May 2, General Belgrano was sunk by the submarine HMS Conqueror. After that, the Argentine Navy went back to its own waters and did not take part in the conflict anymore.

A study by the United States Marine Corps concluded:

The most critical judgement of the use of the Vulcan centres on the argument that their use was "...largely to prove [the air force] had some role to play and not to help the battle in the least." This illustrates the practice of armed services to actively seek a "piece of the action" when a conflict arises, even if their capabilities or mission are not compatible with the circumstances of the conflict. Using Black Buck as an example shows the effects of this practice can be trivial and the results not worth the effort involved.

Images for kids

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |