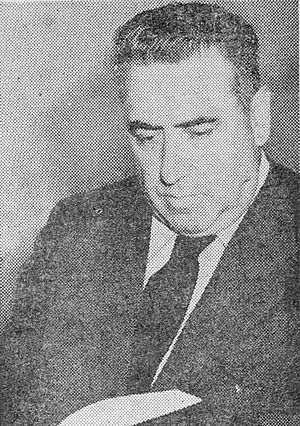

Pablo de Rokha facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pablo de Rokha

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Carlos Ignacio Díaz Loyola 17 October 1894 Licantén, Chile |

| Died | 10 September 1968 (aged 73) Santiago, Chile |

| Occupation | Poet, teacher |

| Notable awards | Premio Nacional de Literatura in 1965 (Chile) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Pablo de Rokha (born Carlos Ignacio Díaz Loyola) was a famous Chilean poet. He lived from 1894 to 1968. He won Chile's National Literature Prize in 1965. People consider him one of the four greatest Chilean poets. The others are Pablo Neruda, Vicente Huidobro, and Gabriela Mistral. De Rokha was known for his unique and modern style of poetry. This style is called avant-garde, meaning it was new and experimental for its time.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Family

Pablo de Rokha was born in the small town of Licantén, Chile. His parents were Ignacio Díaz Alvarado and Laura Loyola Muñoz. He was the oldest of nineteen children! His family were middle-class farmers. De Rokha's father worked in different jobs. He was a farm manager and a customs officer in the Andes mountains. Pablo spent his childhood on a farm called "Pocoa de Corinto." He often went with his father to the Andes border crossings.

School Days and New Ideas

In 1901, de Rokha started Public School Number 3 in Talca. The next year, he joined the San Pelayo de Talca Seminary. A seminary is a school for religious studies. However, he was asked to leave in 1911. This happened because he read books by authors like Rabelais and Voltaire. These books were considered "forbidden" at the time. His classmates gave him the nickname "El amigo piedra," which means "The Stone Friend." He later changed this to "Pablo de Rokha," meaning "Pablo of Stone."

Moving to Santiago and Becoming a Poet

After leaving the seminary, de Rokha moved to Santiago, Chile. He finished high school there. He then started studying Law and Engineering at the University of Chile. But he soon left the university. He decided to focus on poetry and the artistic life of Santiago. He became friends with other thinkers like Pedro Sienna and Vicente Huidobro. Huidobro later started a poetry movement called creationism.

De Rokha also discovered the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche and Walt Whitman. He felt a strong connection to their writings. He worked as a journalist for two newspapers. He also published some of his first poems in a magazine called "Juventud" (Youth).

Love and Marriage

In 1914, de Rokha returned to Talca. He felt he hadn't reached his goals yet. There, he read poems by Juana Inés de la Cruz. This was the pen name of Luisa Anabalón Sanderson. Even though he criticized her poetry, he fell in love with her. He went back to Santiago to find her. In 1916, Luisa Anabalón became his wife. She then changed her pen name to Winétt de Rokha.

The poet went to Luisa's parents' house with a strong attitude. He introduced himself as "a poet, and a very proud one." Luisa's family did not welcome him. Her father, Don Indalecio, even challenged him to a duel! Before the duel, Pablo took Luisa and married her right away. In 1916, he also published some of his early poems in an anthology called "Selva lírica" (Lyric Jungle).

Political Views and Family Life

Between 1922 and 1924, de Rokha lived in San Felipe and Concepcion. He started a magazine called Dynamo. This was a time of big changes in the world. Old ways of governing were ending in Chile. In Europe, powerful movements like Fascism and Nazism were growing. Working-class people in Latin America also started to have more say in politics.

By 1930, Pablo de Rokha strongly supported Marxism–Leninism and Soviet Stalinism. He believed these ideas connected to Christian values. In 1936, he joined the Communist Party of Chile. He also supported the Popular Front of Chile. This group helped Pedro Aguirre Cerda become president in 1938. The Communist Party even made him a candidate for Congress. But he was later expelled from the party in 1940. This was because he didn't follow party rules and criticized other members.

De Rokha published and sold his own books. He never accepted help from publishing companies. He also bought and sold goods to support his growing family. He had many children: Carlos, Lukó, Tomás, Carmen, Juana Inés, José, Pablo, Laura, and Flor. Sadly, some of them died young. Later in life, he also adopted a baby girl named Sandra.

Travels and Later Life

In 1944, President Juan Antonio Ríos named de Rokha a Cultural Ambassador for Chile in the Americas. He traveled through 19 countries. While he was in Argentina, a new president was elected in Chile, Gabriel González Videla. This new president soon created a law that led to the persecution of the Communist party.

In 1949, de Rokha returned to Chile with his wife, Winétt de Rokha. She was suffering from cancer and passed away in 1951. In 1953, de Rokha published "Fuego Negro" (Black Fire). This was a collection of love poems dedicated to his late wife. Winétt's death was the start of many sad events for the family. The loss of his son Carlos deeply affected de Rokha. He wrote a poem called "Carta perdida a Carlos de Rokha" (Lost Letter to Carlos de Rokha).

Pablo de Rokha passed away in 1968. Just two hours after his death, officials from the municipality of La Reina arrived at his house. They came to tell him that they had decided to rename his street in his honor. They did not know he had passed away.

Work

Important critics in Chile once did not like de Rokha's work. However, today his writing is widely studied. He is now considered one of The four greats of Chilean poetry.

Stages of His Work

A literary critic named Naín Nómez divides de Rokha's work into three main periods:

- First Stage (1916-1929): In this period, his work showed influences of romanticism and his ideas of freedom. He mixed these with religious elements. He published works like "Los gemidos" (The Groans, 1922) and "Satanás, Suramérica" (Satan, South America, 1927). Many critics at the time were more interested in modernism, so they didn't pay much attention to his work.

- Second Stage (1930-1950): This time was marked by his political activism. His works included "Canto de trinchera" (Trench Song, 1929–1933) and "Imprecación a la bestia fascista" (Curse the Fascist Beast, 1937). In 1939, de Rokha started his own magazine called "Multitud." It later became a publishing house.

- Third Stage (Last Two Decades): In his later years, de Rokha's works showed a mix of hope, social protest, and sadness over losing his wife. "Fuego negro" (Black Fire, 1953) is an example of this.

Rivalry and Recognition

De Rokha had a famous rivalry with Pablo Neruda. This became more intense when he published "Neruda y Yo" (Neruda and I, 1955). In this essay, de Rokha called Neruda a "bourgeois artist" and accused him of copying others. The debate continued with his book "Genio del pueblo" (Genius of the People, 1960).

In 1965, he won the National Prize for Literature. At the ceremony, he said it came "late, almost as a compliment." He also joked that they gave it to him because they thought he wouldn't cause any more trouble. In 1967, he published his last book, Mundo a mundo: Francia (World to World: France).

Example of work

|

..... |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pablo de Rokha para niños

In Spanish: Pablo de Rokha para niños

- Chilean literature

- Chilean culture