Paul Wild (Australian scientist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Paul Wild

|

|

|---|---|

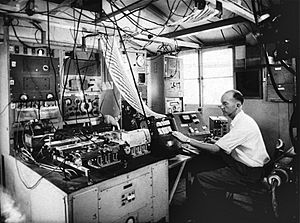

Wild when chairman of CSIRO

|

|

| Born | 17 May 1923 |

| Died | 10 May 2008 (aged 84) |

| Alma mater | Peterhouse, Cambridge |

| Known for | Radio observations of the Sun, invention of microwave landing system, chairmanship of CSIRO, instigation of Very Fast Train project |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Radio astronomy, solar physics, microwave navigation |

| Institutions | Royal Navy, CSIRO |

Dr John Paul Wild (17 May 1923 – 10 May 2008) was a famous scientist from Australia, born in Britain. He served in the Royal Navy during World War II as a radar officer. After the war, he became a radio astronomer in Australia. He worked for the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, which later became the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

In the 1950s and 1960s, Dr. Wild made amazing discoveries by studying the Sun using radio waves. He and his team built special instruments to observe the Sun. Later, he invented a system called Interscan. This system helps planes land safely. From 1978 to 1985, he was the chairman of CSIRO. He helped the organization grow and change. After CSIRO, he led a project to build a high-speed railway in Australia.

Contents

Early Life and Interests

John Paul Wild was born in Sheffield, England, on 17 May 1923. His family faced tough times when his father's business failed. His mother moved with the boys to Croydon, near London. He described these years as "very, very poor." Later, things got better for his family.

He had a happy childhood. He loved building things with model kits and Meccano. A toy train from his mother sparked his lifelong love for trains. He was inspired by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, a famous engineer who built railways and ships. Paul Wild also loved cricket and was known as a "walking encyclopedia of cricket knowledge."

From a young age, he was very curious and loved mathematics. He spent many years studying math in school. During World War II, he and his friends would watch air battles from their school. This was during the Battle of Britain, as their school was near Croydon Aerodrome, a base for fighter planes.

Wartime Service and Science Journey

World War II changed Paul Wild's path. In 1942, he went to University of Cambridge to study mathematics. However, he soon realized he needed to do something for the war effort. So, he switched to "physics with radio."

After university, he joined the Royal Navy. He became a radar officer. Radar was a new technology that helped ships detect objects. In July 1943, at age 20, he was put in charge of radar operations on the battleship HMS King George V. This ship became the flagship of the British Pacific Fleet. He was present when the peace treaty was signed in Tokyo Bay at the end of the war.

Paul Wild saw how radar helped gunners hit targets. He described the excitement of seeing targets on his radar screen. After the war, he taught radar to other naval officers. While on a break in Australia, he met and got engaged to Elaine Hull. He moved to Sydney to be with her. His future brother-in-law joked that Australia should thank Elaine for bringing such a great scientist to the country.

Discovering the Sun's Secrets

In Australia, Paul Wild started as a research officer at the Radiophysics Laboratory near Sydney. He joined a team studying the Sun. During the war, scientists discovered that mysterious radio interference was actually noise coming from the Sun.

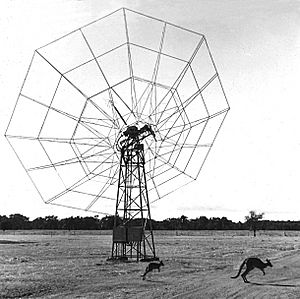

Wild chose to work on building a radiospectrograph. This was the first instrument of its kind. It looked at the radio waves coming from the Sun. It helped scientists understand the complex bursts and storms on the Sun. His team set up their equipment at Penrith, New South Wales, and later at Dapto, south of Wollongong.

His team identified three types of solar bursts: Type I, Type II, and Type III.

- Type II bursts were linked to shock waves moving through the Sun's atmosphere. These waves traveled at 1,000 kilometers per second. They were connected to auroras (like the Northern Lights) seen on Earth about 30 hours later. This solved a long-standing mystery: what caused disturbances from solar flares to reach Earth? Today, Type II bursts are watched closely for "space weather" reports. Space weather can affect radio communication and satellites.

- Type III bursts were linked to streams of electrons shot out from the Sun. These electrons traveled at one-third the speed of light. They reached Earth in less than half an hour. Later, satellites confirmed these electron bursts.

Wild's team's discoveries helped classify solar bursts. Their names for these phenomena became the international standard.

Leading Solar Research Globally

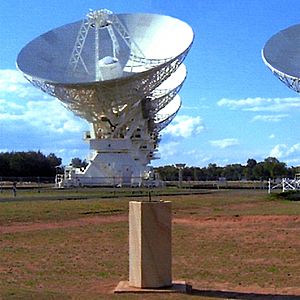

Paul Wild's team then built a huge instrument called a radio-heliograph at Culgoora, near Narrabri, New South Wales. This instrument was three kilometers wide. From 1967, it produced real-time images of solar activity. It showed how the Sun's outer layer, the corona, worked.

The radio-heliograph helped scientists "see" solar phenomena directly. It operated for 17 years, providing a lot of data. It also helped during the Skylab space missions. The Culgoora site is now home to the Paul Wild Observatory.

Paul Wild was always eager to share his love for science. From 1962, he helped bring high-level science teaching to high school students across Australia. These sessions were televised live from the University of Sydney.

Innovating with Interscan

In 1971, Paul Wild became the chief of CSIRO's Division of Radiophysics. He wanted to show that their research could be useful in real-world applications.

He learned that the International Civil Aviation Organization was looking for a new system to help planes land. Wild quickly came up with the idea for Interscan, a microwave landing system. This system uses radar beams that scan horizontally and vertically. This tells the aircraft its exact position, even in bad weather.

Interscan had many benefits. It worked well in all weather. It also allowed for many channels to avoid interference. In 1978, Interscan was accepted as the new global standard. This happened after many difficult international talks. Paul Wild showed great skill as a diplomat during these negotiations.

However, Interscan did not become widely used. This was mainly because the US Federal Aviation Administration developed a different system called Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS). WAAS uses satellites and is cheaper, but Interscan is more accurate in very low visibility.

Leading National Science

In 1978, Paul Wild became the Chairman of CSIRO. He held this important role until 1985. He led the organization through big changes. He wanted CSIRO to work more closely with industries and the community.

Wild believed that research needed to be excellent and original. During his time, he secured funding for major research facilities. These included a research vessel, an animal health laboratory, and the Australia Telescope. He also created a new Division of Information Technology.

Being Chairman was not always easy. He faced challenges like budget cuts and public criticism. He found it frustrating to bring in new young scientists because of less funding. Despite these challenges, his leadership helped CSIRO and Australia greatly. He retired from CSIRO in 1985.

The Very Fast Train Project

After CSIRO, Paul Wild led the Very Fast Train Joint Venture. This project aimed to build a high-speed railway between Sydney, Canberra, and Melbourne.

The Idea and Early Plans

In 1983, Wild took a train trip and thought about a faster railway. In 1984, he and other experts published a proposal for a fast railway. It remarkably predicted the main issues for building such a railway in Australia.

The proposed route would connect Sydney, Canberra, and Melbourne. It aimed to serve people in coastal areas and encourage growth outside big cities. The project faced challenges from the government. Some officials thought it was too grand and not worth studying.

Paul Wild believed Australia needed new ideas and should not stick to old ways of thinking. He called for an independent study of the project. He was not asking for government money, just support for a study.

Building Support and Facing Challenges

Soon, a transport company leader, Peter Abeles, offered to help. He saw the potential for national development. Wild then brought together a group of companies to form the joint venture. He became its chairman.

In 1987, a study showed the project was possible and could make money. The plan was for trains to travel up to 350 kilometers per hour. The project needed support from different governments (federal, New South Wales, Victoria, and Australian Capital Territory).

The public and media were very interested. Public support for the project was strong. Surveys showed high support in Victoria and New South Wales.

The Project's End

In 1990, the joint venture chose an inland route for the train. This was a difficult decision, as the original coastal route would have helped develop regional areas. The decision disappointed Peter Abeles, who believed the project had "lost the plot" by going inland.

The project faced other problems. The companies in the joint venture did not always agree. Dealing with four different governments was also hard. They often focused on problems instead of opportunities. The biggest hurdle was about tax rules. The federal government was not willing to change tax laws to help the project.

In August 1991, the federal government gave its final "no." The joint venture stopped work on the project. Paul Wild felt bitter about this decision. He believed the government was short-sighted. He also thought the project's structure and delays had hurt it.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1991, Paul Wild's wife, Elaine, passed away. He later married Margaret Lyndon, and they had 12 happy years together. In his later years, he continued to work on scientific theories, especially about gravity and the universe. He discussed these ideas with his stepson, Tom Haddock, who was also a scientist.

Paul Wild considered his most important achievement to be building the Culgoora radio-heliograph. This instrument gave the world a unique way to see and record the Sun's activity.

He was also a lover of classical music, a master of crosswords, chess, and bridge, and a railway enthusiast. He had a great sense of humor and was known for his kindness and ability to explain complex ideas simply. He always gave credit to his colleagues.

Paul Wild passed away in Canberra on 10 May 2008.

Honours

Paul Wild received many awards for his research and science leadership:

- Edgeworth David Medal, Royal Society of New South Wales (1957)

- Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1961)

- Member, American Philosophical Society (1962)

- Fellow, Australian Academy of Science (1964)

- Inaugural Arctowski Medal, United States National Academy of Sciences (1969)

- Balthasar van der Pol Gold Medal, International Union of Radio Science (1969)

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1970)

- Inaugural Herschel Medal, Royal Astronomical Society (1974)

- Matthew Flinders Medal and Lecture, Australian Academy of Science (1974)

- Thomas Ranken Lyle Medal, Australian Academy of Science (1975)

- Fellow, Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering (1977)

- Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) (1978)

- Royal Archive winner, The Royal Society (1980)

- George Ellery Hale Prize for Solar Astronomy, American Astronomical Society (1980)

- ANZAAS Medal, Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science (1984)

- Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) (1986)

- Hartnett Medal, Royal Society of Arts London (1988)

- Centenary Medal (2001)

Memorial

At Culgoora, New South Wales, there is a sundial dedicated to Paul Wild. It is located at the Paul Wild Observatory, which is home to the Australia Telescope Compact Array. The sundial reads: "In memory of Paul Wild, founder of this observatory."

Images for kids

See also

- Wild's Triplet

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |