Orosius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Orosius

|

|

|---|---|

Paulus Orosius, shown in a miniature from the Saint-Epure codex.

|

|

| Born | c. 375/85 AD |

| Died | c. 420 AD |

| Occupation | Theologian and historian |

| Scientific career | |

| Influences |

|

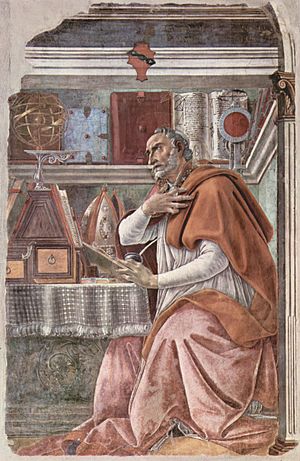

Paulus Orosius (born around 375/385 AD – died around 420 AD) was a Roman priest, historian, and theologian. He was also a student of Augustine of Hippo, a very important Christian thinker. It's believed he was born in Bracara Augusta (now Braga, Portugal). This city was the capital of the Roman province of Gallaecia.

Orosius was well-respected for his knowledge. He met with famous people of his time, like Augustine of Hippo and Jerome. To meet them, he traveled across the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea to cities like Hippo Regius, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. These journeys shaped his life and his writings. He didn't just talk about religious ideas with Augustine. He also helped Augustine with his famous book, City of God.

In 415, Orosius traveled to Palestine to share ideas with other scholars. He also attended a Church meeting in Jerusalem. On this trip, he was trusted to carry the relics of Saint Stephen. The exact date of his death is not clear. However, it was likely after 418 AD, when he finished one of his books, and before 423 AD.

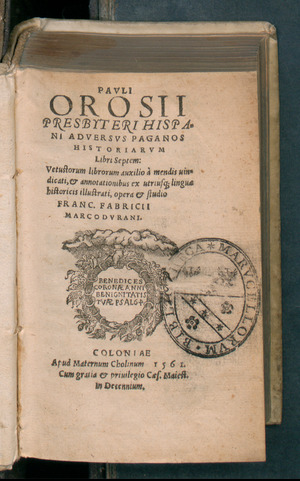

Orosius wrote three books. His most important work is Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (in Latin: Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII). This book had a huge impact on how history was written from ancient times to the Middle Ages. It's also considered one of the most important Spanish books ever. In this book, Orosius explained his methods for writing history. He focused on the history of pagan peoples from the earliest times up to his own era.

Orosius was very influential. His History Against the Pagans was a main source of information about ancient times until the Renaissance. His way of studying history also greatly influenced later historians.

Contents

Who Was Paulus Orosius?

Even though his books are important, many details about Orosius's life are still a mystery. This makes it hard to write a full biography, especially about his birth and death. However, many scholars have studied his life and suggested dates for these events.

The main information about Orosius comes from the writings of Gennadius of Massilia and Braulio of Zaragoza. Orosius also wrote about himself, and Augustine mentioned him in letters.

What Was His Real Name?

We are sure about his last name, Orosius. But there are questions about his first name, "Paulus." It's not completely certain if he used this name. Some think "Paulus" might have been added later. This could have happened because the letter "P" (for "presbyter," meaning priest) was often placed next to his name. Over time, this "P" might have been mistaken for "Paulus."

However, authors writing soon after Orosius's death did use the name Paulus. One main scholar, Casimiro Torres Rodríguez, even suggested that Paulus might have been his Christian name, and Orosius his birth name. This idea is still considered possible.

Where Was Orosius Born?

His birthplace is still debated, but most experts now agree on one idea. There are four main theories about where he was born:

- Born in Braga: This is the most accepted idea because it has the most proof. If he wasn't born exactly in Braga, it was likely in the area nearby. Orosius's own writings and two letters from Augustine support this.

- Born in Tarragona: This idea came from Orosius writing "Tarraconem nostra" (our Tarragona) in his Histories. But today, this single clue isn't enough to support the theory.

- From A Coruña (Brigantia): This is a newer idea. It's based only on Orosius mentioning this place twice in his Histories.

- From Brittany: This theory also relies on Orosius showing some knowledge of this area.

When Was Orosius Born?

His birth date varies among sources, but a likely period has been figured out. We know that in 415 AD, Augustine called Paulus Orosius "a young priest." This means he couldn't have been older than 40 (because he was "young") and had to be older than 30 (because he was a priest).

So, his birth date is likely between 375 and 385 AD. The most commonly accepted date is 383 AD. This would mean he was 32 when he met Augustine, having been a priest for two years.

Orosius's Life Story

His Early Life

We don't have many sources about his early life. But if he was born between 375 and 385 AD, Orosius grew up during a time of great cultural activity. He lived at the same time as other important figures like Hydatius. It's thought that after he became a priest, he became interested in the Priscillianist debate, which was a big topic in his home country.

Old theories suggest Orosius came from a well-off family. This would have allowed him to get a good education, likely focused on Christianity. If he was born in Braga, he would also have known a lot about the rural culture of that time.

Writers from his time said Orosius was smart and spoke well. Both Augustine and Pope Gelasius I mentioned this. However, most of what we know about Orosius's youth is guesswork because there's so little information.

Journey to Africa

Paulus Orosius likely lived in Gallaecia (northwest Hispania) until 409 AD. After that, until 415 AD, we don't have clear information about his life. The most common timeline suggests the following events.

Orosius probably had to leave Braga because of the barbarian invasions of the Roman Empire. The exact date he left is uncertain, but we know he had to leave suddenly. Orosius himself said he was chased to the beach where he sailed away.

Several dates have been suggested for his departure from Braga, from 409 to 414 AD. The two most accepted dates are:

- 410 AD: This date was suggested by G. Fainck. It would mean Orosius had five years to work with Augustine before traveling to Palestine.

- 414 AD: This is the most widely accepted date. In his book Commonitorium, published in 414, Orosius talks about arriving and meeting Augustine.

What is certain is that once Orosius left the Iberian Peninsula, he aimed for Hippo (now Annaba in Algeria). He wanted to meet Augustine, who was the greatest thinker of his time. From the moment he arrived, Orosius became part of Augustine's team. It's possible Orosius helped write The City of God or at least knew about the book.

In 415 AD, Augustine asked Orosius to travel to Palestine. He was to meet with Jerome, another important thinker who lived in Bethlehem. This shows that Augustine trusted Orosius a lot, as Augustine and Jerome hadn't always had good relations.

Journeys to Palestine

Orosius's visit to Palestine had two main goals. First, he wanted to discuss religious topics with Jerome, especially about where the soul comes from. Second, Augustine wanted to build stronger ties with Jerome. He also wanted to get information about different religious groups, like the Priscillianists and Pelagians.

It seems Orosius's main job was to help Jerome and others against Pelagius. Pelagius had been living in Palestine and gaining followers. Orosius met with Pelagius on Augustine's behalf. He also represented the traditional Christian view against the Pelagians at the Synod of Jerusalem in June 415 AD.

At the meeting, Orosius shared the decisions made at the Carthage meeting. He also read some of Augustine's writings against Pelagius. However, he didn't fully succeed with the Greeks there, who didn't understand Latin. Pelagius famously asked, Et quis est mihi Augustinus? ("Who is Augustine to me?"), showing he wasn't impressed.

Orosius only managed to get the local bishop, John, to agree to send letters to Pope Innocent I in Rome. After waiting for the unfavorable decision of another meeting (the Synod of Diospolis) in December, Orosius returned to North Africa.

Orosius had a disagreement with the Archbishop of Jerusalem, John II, at the synod. Orosius was accused of heresy. To defend himself, Orosius wrote his second book, Liber Apologeticus. In it, he strongly denied the accusation.

When Orosius first met Jerome, he gave him letters from Augustine. This suggests the trip was always meant to be a round trip, as Orosius would bring Jerome's letters back to Augustine. Also, the relics of Saint Stephen were found at the end of 415 AD. A part of them was given to Orosius to take back to Braga. This marked the start of his journey home and a new period in Orosius's life, which we know little about.

His Later Years

Since Stephen's relics were found on December 26, 415 AD, Orosius must have left Palestine after that date. Although he planned to go to Braga, he had to stop in Hippo. We know he delivered letters from Jerome to Augustine there. It's also generally agreed that he passed through Jerusalem and Alexandria, though we don't know if he visited Alexandria on his way there, on his way back, or both.

During his second stay in Hippo, he had a long talk with Augustine. He gave Augustine the letters from Jerome and told him about his meetings with Pelagius. It was during this meeting that the idea for Orosius's great work, Historiae Adversus Paganos, was born. However, it's hard to say exactly when the book was written and finished. This has led to several theories:

- Traditional theory: The book was finished between 416 and 417 AD. This is supported because his Liber Apologeticus doesn't mention his work as a historian. Also, the introduction refers to Augustine's Book XI of City of God, which came out in 416. To explain how Orosius wrote seven books so quickly, some think he might have written summaries first and then filled them out.

- Recent theory: Casimiro Torres Rodríguez suggests Orosius briefly stayed in Stridon a second time while trying to return to Portugal, which he couldn't do. He then wrote the book during a third stay in Stridon. This would explain why Orosius mentions events in Hispania from 417 in his Histories.

- Older theory: T. von Mörner and G. Fainck thought Orosius started the work before his trip to Palestine. This idea has recently been revived by M. P. Annaud-Lindet, who suggests Orosius wrote the book during his return journey from Palestine.

Where Did He Go?

Very little information exists about Paulus Orosius's life after his Histories were published. We know he was in Menorca, where he used Stephen's relics to try and convert Jewish people to Christianity. But the date of his death is unknown. This lack of information might be because his relationship with Augustine cooled. Augustine never clearly mentioned Orosius's Histories after they were published. Gennadius of Massilia believed Orosius lived until at least the end of the Roman emperor Honorius’ reign, which was 423 AD. However, there's no news of Orosius after 417 AD. It seems unlikely that such an active writer would go six years without publishing anything new.

Other theories exist, from a sudden death to legends about Orosius finally reaching Hispania and starting a monastery near Cabo de Palos. But this last idea now seems unlikely.

Orosius's Writings

Commonitorium and Liber Apologeticus

While Paulus Orosius's most important book was Historiae Adversus Paganos, his other two surviving books are also important: Commonitorium and Liber Apologeticus.

His first book's full name is Consultatio sive commonitorium ad Augustinum de errore Priscillianistarum et Origenistarum. This means "A Warning and Reminder to Augustine Against the Errors of the Priscillians and the Origenists." The exact timeline for this book is as unclear as Orosius's life. It was meant for Augustine, so it must have been written before Orosius arrived in Africa, between 409 and 414 AD. The latest possible date is 415 AD, when Augustine's book Liber ad Orosium contra Priscillianistas et Origenistas was published, which was Augustine's reply to Orosius's Commonitorium.

This book not only describes Orosius's journey to Africa but also summarizes the beliefs of Priscillianism and Origenism. It asks for Augustine's advice on these religious matters, showing some of Orosius's own religious questions.

Orosius's second book is called Liber apologeticus contra Pelagium de Arbitrii libertate. It was published when Orosius was at the Council of Jerusalem in 415 AD. This book came from a religious debate where Archbishop John II accused Orosius of heresy. This was because Orosius believed that humans cannot be completely free of sin, even with God's help.

To defend himself, Orosius wrote Liber Apologeticus. In it, he explained why he attended the meeting (Jerome invited him) and rejected the heresy accusation. However, neither of these two books are history books, even though they contain details that help us understand Orosius's life.

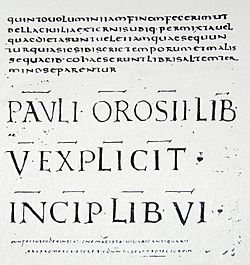

Historiae Adversus Paganos

Paulus Orosius's most famous work is Historiae Adversus Paganos. This is the only history book he wrote. It shows how Spanish priests wrote history back then. We can't be sure when it was written, as historians have different ideas. The most common guess is between 416 and 417 AD.

Miguel Ángel Rábade Navarro, a scholar, describes Orosius's history as a "universalist history with an apologetic and providentialist character." This means its main goal was to compare the pagan past with the Christian present. It did this by looking at people, their actions, and where and when they lived.

The book had a clear purpose. Augustine wanted a book that would go along with his De Civitate Dei. Orosius's book focused on the history of pagan peoples. Orosius wanted to prove that Rome's decline – especially after Rome was attacked by Alaric I in 410 AD – had nothing to do with Romans becoming Christians.

More generally, Orosius wanted to show that the world had actually gotten better since Christianity arrived, not worse. People at the time pointed to disasters, but Orosius argued that disasters before Christianity were much worse. His work was a universal history of human suffering. It was the first attempt to write world history as God guiding humanity.

In his seven books, Orosius used new methods and also traditional ones from Greek and Roman history writing. Orosius never showed pagans in a negative light. This was true to the style of Greek-Roman historians, who often tried to show their "enemies" in a positive way.

How the Book Spread

The Histories were printed many times. At least 82 copies from ancient times and 28 early printed versions still exist. There are also copies in Italian and German from the 16th century. Johannes Schüssler printed the Historiae in Augsburg in 1471.

Translations

- An older, shorter translation into Old English, called the Old English Orosius, is often linked to King Alfred.

- An Arabic translation, called Kitāb Hurūshiyūsh, was supposedly made during the rule of al-Hakam II of Córdoba.

- A 13th-century Italian translation by Bono Giamboni.

- An unpublished 14th-century Aragonese translation, made by Domingo de García Martín.

- A French translation from 1491.

- A German translation from 1539.

- The Seven Books of History against the Pagans: The Apology of Paulus Orosius, translated by Irving Woodworth Raymond (1936).

- Seven Books of History against the Pagans, edited and translated by A. T. Fear (2010).

Its Impact

Even if Paulus Orosius and Augustine had a falling out, it didn't stop his Histories from spreading and having a big impact. Despite some criticisms, Orosius's books were successful almost from the day they were published. Nearly 200 copies of the Histories have survived.

The Histories were considered one of the most important works of Spanish history writing until the Reformation. This success also helped preserve Orosius's other works.

Historiae Adversus Paganos was quoted by many authors, from Braulio of Zaragoza to Dante Alighieri. It was one of the main books used by students of Ancient History throughout the Middle Ages. Through its Arabic translation, it became a source for Ibn Khaldun in his history. Lope de Vega even made Orosius a main character in his play The Cardinal of Bethlehem, showing how long his fame lasted.

How Orosius Wrote History

Universal History

The "universal" nature of Orosius's work is perhaps its most important feature. While experts disagree on many things about Orosius, most agree that his work is universalist. This means it tries to cover all of world history. Many see it as the first Christian universal history, or the last classical universal history.

Paulus Orosius not only wrote history but also explained his own ideas about how to write it in the introductions to his books. He was always clear about his goals: he wanted to write history from the creation of the world up to his own time. This clearly shows his aim to be a universal historian.

Orosius used the "succession of the four world empires theory." This idea traced world history by saying that when one great civilization fell, another rose from its ruins. His theory was based on four historical empires: Babylonia, pagan Rome, Macedonia, and Carthage. He saw Christian Rome as the fifth empire, inheriting from all of them. He showed how the first four empires developed similarly, with striking parallels. But Rome, which Orosius praised, was different.

Orosius's new idea in this theory was to place Carthage between Macedonia and Rome. Scholars like García Fernández point this out as one of Orosius's key and lasting contributions.

Patriotism and Universalism

Another important feature of Orosius's Histories is its patriotism. There are two main views on Orosius's patriotism: a traditional view by Torres Rodríguez and a newer view by García Fernández.

Torres Rodríguez's theory says Orosius showed patriotism by focusing on events in Hispania (modern-day Spain and Portugal). This makes sense given where Orosius was from. Examples include stories in the Histories about events in Braga. Some even say Orosius's stories are used by modern Galician nationalists.

However, in 2005, García Fernández argued that calling Orosius's historical method "patriotic" was an exaggeration. He rejected many of Torres Rodríguez's ideas on this. García Fernández used the idea of "localism," which was popular among historians in the early 21st century. This idea suggests that beyond "Hispanism," Orosius simply showed a "kind attitude" towards Hispania.

Optimism and Pessimism

Another interesting point is how Orosius was pessimistic about some topics and overly optimistic about others. Generally, he was pessimistic about anything related to paganism or the past. But he was optimistic about Christianity and his own time, which is surprising given the difficult times he lived in.

These traits influenced all his other ideas. It's especially clear when he focuses on the suffering of the defeated and the horrors of war. This can be linked to Augustine's influence, as Orosius shows two sides of a story, much like Augustine's idea of dualism.

Orosius presented the past as a series of hardships, with examples from Noah's flood to shipwrecks. He presented the future as positive, despite the harsh reality of his time.

To tell a story of suffering and tragedy, he often focused on defeats. This was different from typical Roman history, which usually highlighted victories. However, this approach sometimes led to problems. To convince his readers, Orosius sometimes described myths and legends as if they were real historical facts.

Another common criticism of Orosius's work relates to this mix of pessimism and optimism. It often made his writing seem less objective. This divides historians: some see him as biased, while others say his approach is justified because he viewed history the way Christians view life. In other words, his approach is seen as based on his belief in God's plan for humanity.

His Storytelling Style

Orosius's skill as a storyteller should not be overlooked. He had a clear goal: to defend Christians from the accusations of non-Christian Romans. These Romans blamed Christians for the attack on Rome in 410 AD, saying it was punishment for abandoning the city's old gods.

Orosius's storytelling abilities went beyond just being pessimistic or optimistic. His main idea was that the past was always worse than the present because it was further from the true religion.

Having clear goals meant he wrote his stories with a definite purpose. So, he narrated some events with little detail and others with full detail. Orosius always seemed to have enough information. He even said that a historian should choose their sources carefully. It seems his different levels of detail simply showed what he wanted to emphasize to support his ideas.

Because his writing had a moral and defensive purpose, he focused on unusual events, like the suffering of ordinary people during war. This choice of facts helped him write about patriotism, for example, as he always paid a lot of attention to events in Hispania.

Why Geography Was Important

Another important part of Orosius's work is how much importance he placed on geography. He showed this in his description of the world in the second chapter of the first of his seven books, the Histories.

One weakness in his geography was his lack of precision. For example, he often used the name "Caucasus" to refer to other nearby mountain ranges. Despite this vagueness, it's notable that the Histories included a chapter on geography. This has made his work more valuable in modern history studies, thanks to scholars like Lucien Febvre and Fernand Braudel.

What Sources Did Orosius Use?

The sources Orosius used have been studied by Teodoro de Mörner. Besides the Old and New Testaments, he seems to have looked at writings by Caesar, Livy, Justin, Tacitus, Suetonius, Florus. He also valued Jerome's translation of the Chronicles by Eusebius.

See also

In Spanish: Paulo Orosio para niños

In Spanish: Paulo Orosio para niños