Peter French facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Peter French

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | April 30, 1849 Missouri, United States

|

| Died | December 26, 1897 (aged 48) Frenchglen, Oregon, USA

|

| Occupation | Rancher |

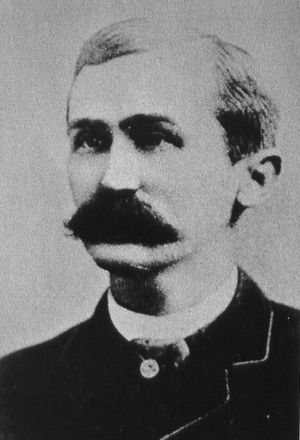

Peter French (born April 30, 1849 – died December 26, 1897) was a famous rancher in the western United States during the late 1800s. The town of Frenchglen, Oregon was partly named after him. He became known for owning a very large cattle ranch.

Contents

Early Life and Moving West

Peter French was born John William French in Missouri on April 30, 1849. When he was very young, his family moved to Colusa County, California. His father started a small ranch there. However, there wasn't enough land for everyone because of old Spanish land grants.

So, French's family moved north in the Sacramento Valley. His father then started a successful sheep ranch. But as Peter grew up, he wanted more exciting work.

French moved south to Jacinto, California. There, he got a job as a horse breaker for Dr. Hugh J. Glenn. Glenn was a rich stockman and wheat farmer. French learned quickly and soon became a foreman. He even learned Spanish, and the vaqueros (cowboys) working for Glenn respected him. Around this time, he started using the name "Peter."

Starting the P Ranch

Dr. Glenn wanted to expand his business. In 1872, he sent French to Oregon. French took 1,200 Shorthorn cattle, some vaqueros, and a cook. He went to southeastern Oregon, where he found huge grasslands in the dry high desert.

In the Catlow Valley, French met a prospector named Porter. French bought Porter's small cattle herd and his "squatter's rights" to land near Steens Mountain. He also bought Porter's "P" brand for cattle.

French then found the Blitzen Valley. The Donner und Blitzen River flowed through it for about 40 miles. This became his favorite spot. He built shelters for his cattle, cabins, and bunkhouses for his workers. This was the beginning of the famous P Ranch.

Building a Cattle Empire

Over several years, French's ranch grew much larger. Dr. Glenn helped by providing money. The P Ranch became the main place for French's growing cattle business.

French and his workers built fences and drained wet areas to make more pasture. They also watered large areas of land. They trained many horses and mules and harvested hay. French's land grew to include the Diamond Valley, the Blitzen Valley, and the Catlow Valley. This huge area was about 160,000 to 200,000 acres.

French was a smart businessman. He used a law called the Swamp and Overflow Act. This law allowed people to buy marshland cheaply. French would build dams to flood areas, buy the land at a low price, and then remove the dams to make the land usable again. He also had his employees and others file homestead claims. He would then buy these claims from them. He even fenced off some public lands.

In 1883, French married Ella Glenn, Dr. Glenn's daughter. Sadly, Dr. Glenn was killed three weeks later. French continued to manage the Oregon ranch for the Glenn family. He sold more cattle to help the family pay their debts. In 1894, the Glenn family formed the French-Glenn Livestock Company. French became the company president. He divorced in 1891.

Challenges and Conflicts

In June 1878, Paiute and Bannock people (who were connected to the Shoshone tribes) attacked the P Ranch. A messenger warned French, and he and most of his men escaped. The attacks continued that summer. The Paiutes burned buildings and took cattle and horses. French even helped the U.S. 1st Cavalry Regiment guide the Army through the area.

In the 1880s and 1890s, big ranchers and smaller farmers often argued over land and water rights. French's large land holdings and his actions made some people dislike him.

Peter French's Death

Peter French was shot and killed on December 26, 1897, by Edward Lee Olivier. He died right away.

John William "Peter" French was buried in Red Bluff, California. His grave is next to his parents at the Oak Hill Cemetery.

Disputes Leading to His Death

French's desire for more land led him to have disagreements with local homesteaders. He tried to get them to leave their properties. In 1896 and 1897, the French-Glenn company started legal actions against several homesteaders. This made the homesteaders very angry. French chose to file these lawsuits in a faraway courthouse in Portland, Oregon. He did this to make it harder and more expensive for the homesteader families to defend themselves. He also thought a jury in Portland might be more favorable to him than a local jury.

The Portland court sent the cases back to the Harney County courthouse, where they belonged. This led to many more legal filings from both the homesteaders and French-Glenn. The tension against French grew very strong. Many people, including French himself, believed that these conflicts might lead to him being harmed.

The Trial of Edward Olivier

Edward Olivier was charged with murder. He said he was not guilty. Seven local people helped him post $10,000 bail. The day before the trial was supposed to start, the murder charges were changed to a lesser charge of manslaughter. Some of French's supporters felt the trial was unfair. The trial began on May 18, 1898, in the Harney County Courthouse.

Olivier and French had been arguing for some time about a path. Olivier wanted the legal right to cross French's land to get to his home. Without this path, Olivier would have to travel an extra six miles. Several people said that French often tried to embarrass Olivier for supposedly trespassing. A rancher named Alva Springer testified that French publicly ridiculed Olivier. He said French told Olivier, "Here sits a little man who has nothing to say. You were in my field yesterday. Whenever the time comes right and I catch you there, I will fix you." Other witnesses also said they heard French threaten to "fix" or even "shoot" Olivier.

The state called nearly twenty witnesses, including seven of French's employees. They saw the shooting from different distances. Their stories were mostly similar. They said Olivier rode toward a gate on French's land. French was working with cattle at the gate. Witnesses saw Olivier's horse bump French's horse, and French yelled at Olivier. French was seen swinging his hand as if he had a whip, but witnesses couldn't clearly see a whip because of the distance. Olivier continued past French toward his home. French turned his horse around. Olivier then pulled out his gun and aimed it at French's head. French ducked. Olivier lowered his gun. When French looked back at Olivier, Olivier raised his gun again and fired. French fell from his horse. Olivier stopped, looked at French on the ground, and then rode away toward his home.

Olivier's defense argued that he feared French was about to draw a weapon and "fix" him when French turned his head. French did not have a gun, but he was carrying his horse whip.

Burt French, Peter French's brother and an employee at P Ranch, was one of the witnesses for the prosecution. He said, "Never saw my brother strike Olivier with anything."

More than twenty witnesses testified for Olivier's defense. One witness, J. P. Kennedy, said he saw Burt French in Portland, Oregon, a little over a week after Peter French was killed. Kennedy testified that Burt French told him, "I don't like to say anything against my brother, but I can't blame Olivier for doing as he did."

The jury found Edward Olivier not guilty.

Unanswered Questions

There are two stories that add to the mystery of Peter French's death.

The first story comes from Emanuel Clark, one of French's crew members. He told his version of events to a man named John Scharff. On Christmas Day, 1897, French and his crew were driving cattle. French traded his wagon with his injured right-hand man, Chino. French took Chino's horse. Before Chino left, French took his pistol out of its holder and put it on. But then he changed his mind. He took the pistol off, put it in his pack, and told Chino to take the pack back to French's room at P Ranch. Everyone present saw that French would be working without a weapon.

Later that night, Emanuel Clark and French decided to stay at the Sod House. A new worker named Caldwell said he would camp with friends and meet them the next morning. But Caldwell never showed up.

The second story comes from Clara Springer. She was the granddaughter of Alva Springer, a homesteader who was in a legal dispute with French. In 1994, an author named Edward Gray interviewed Clara Springer for his book. During the interview, Clara kept saying, "I know something about the death of Pete French that nobody knows." She then shared her secret. She said Olivier lied during his trial. Olivier had said he went straight home after leaving the George Curtis place on the day of the shooting. But Clara said that wasn't true. She said Olivier met Alva Springer on a hill overlooking French and his cattle. Another man, Albert Reineman Sr., was also there. Clara said Springer warned Olivier that he should take the longer six-mile journey home.

Some people think Caldwell might have learned that French was unarmed on Christmas Day. They believe this information might have spread quickly. Even if it did, it doesn't prove whether Olivier acted in self-defense or if the shooting was planned. French's history of trying to control Olivier might have led Olivier to feel justified in his actions. Or, perhaps French's death was planned by others. We may never truly know all the details.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |