Peter Nicholson (architect) facts for kids

Peter Nicholson (born July 20, 1765 – died June 18, 1844) was a talented Scottish architect, mathematician, and engineer. He learned most things by himself. He started as a cabinet-maker, but soon became famous for teaching and writing.

Even though he worked as an architect, he is best known for his ideas about the skew arch. This is a special type of arch that crosses a road or river at an angle. He also invented tools for drawing, like the centrolinead and a cyclograph. Peter Nicholson wrote many books about practical subjects.

Contents

Peter Nicholson's Life Story

Early Years and Learning

Peter Nicholson was born in 1765 in a place called Prestonkirk, Scotland. His father was a stonemason, someone who cuts and shapes stone.

Peter was mostly self-taught and very good at mathematics. He only went to a local school for three years, from age nine to twelve. After that, he helped his father in the family business. During this time, he enjoyed drawing and making models of the many mills nearby.

He didn't like stonemasonry much. So, he decided to become a cabinet-maker. He trained for four years in Linton. Then, he worked as a journeyman (a skilled worker who travels) in Edinburgh. In 1789, when he was 24, he moved to London.

In London, Peter continued as a cabinet-maker. But he also started teaching geometry at an evening school. He was so good at teaching that he soon stopped making cabinets. Instead, he started writing books.

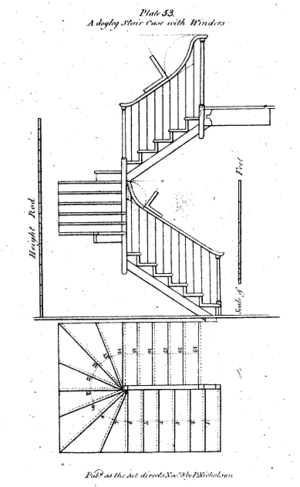

His first book, The Carpenter's New Guide, came out in 1792. He even drew the pictures for it himself! This book was special because it showed new ways to build complex curved shapes in buildings. While in London, he published three more books: The Student's Instructor (1795), The Carpenter and Joiner's Assistant (1797), and Principles of Architecture (1794-1798).

Middle Years and Big Projects

After 11 years in London, Peter Nicholson returned to Scotland in 1800. He was 35 years old. For the next eight years, he worked as an architect in Glasgow. He helped build a wooden bridge over the River Clyde and designed Carlton Place.

A nobleman, the Earl of Eglinton, asked him to plan the new town of Ardrossan. Peter's simple but effective grid plan was used for the town for the next 50 years. A famous engineer named Thomas Telford built the town's harbor. Telford was so impressed with Peter's work that he suggested him for a job in Cumberland.

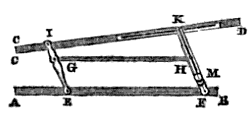

Peter got the job and moved to Carlisle. He helped build the new Courts of Justice there. He also won awards for improving handrail designs and for inventing his drawing tool, the centrolinead. Two years later, he went back to London to teach and write again.

In London, Peter opened a school on Oxford Street. He taught mathematics, architecture, and building skills. He kept improving his centrolinead tool. For this, he received a gold medal and money in 1814, and a silver medal in 1815. Around 1816, a famous artist painted his portrait. This painting is now in the National Portrait Gallery.

The years between 1810 and 1829 were his busiest for writing. He published Mechanical Exercises (1812), The Builder and Workman's New Director (1822), and The Architectural Dictionary (1812 and 1819). This dictionary made him a national expert on building technology. He also wrote about science and mathematics.

In 1826, at age 61, Peter visited France. He learned enough French to translate mathematical books. The next year, he started a big project called The School of Architecture and Engineering. He planned to publish it in 12 cheap books. But the publisher went out of business, and only five books were ever made. This was the only project he didn't finish.

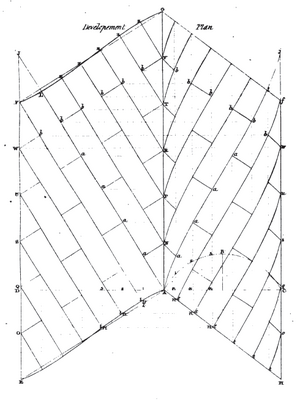

Because he lost a lot of money, Peter left London in 1829 to save money. He moved to Morpeth in Northumberland. There, he lived in a small house he inherited. He published A Popular and Practical Treatise on Masonry and Stone-cutting (1828). In this book, he showed how to cut stones perfectly for a strong skew arch. This made it easier for engineers and stonemasons to build these arches.

Later Life and Last Works

In Morpeth, Peter started writing a book called A Treatise on Dialing. It explained how to make and set up sundials. On August 10, 1832, his wife, Jane, died. He built a memorial for her. Then, he left Morpeth and moved to Newcastle upon Tyne.

At 67, still struggling financially, Peter kept writing. His Treatise on Dialing was published in 1833. He also opened a school in Newcastle, but it didn't make much money. Still, people in Newcastle respected him greatly. He became an honorary member of several local groups.

In 1834, people tried to raise money to buy him a pension. They only raised £320, which wasn't enough. So, they gave the money directly to him. They also asked King William IV to give him a pension. In 1836, he became President of the Newcastle Society for the Promotion of the Fine Arts. In 1838, he gave a speech about "Oblique Bridges" at a science meeting.

During his nine years in Newcastle, Peter published three more books. His Treatise on Projection (1837) included a portrait of him. His last book was The Guide to Railway Masonry, containing a Complete Treatise on the Oblique Arch, published in 1839. This book also had his portrait, showing him as an older, poorer man compared to earlier paintings.

On October 10, 1841, at age 76, Peter left Newcastle for Carlisle. A relative helped support him for the rest of his life. He died on June 18, 1844, and was buried in a churchyard.

In 1865, a monument was built in his memory in Carlisle cemetery. Peter Nicholson was married twice. He had a son, Michael Angelo, with his first wife, Jane. Michael also wrote a book about carpentry. With his second wife, Peter had a daughter, Jessie, and another son, Jamieson T.

How Peter Nicholson is Remembered

As a Math Whiz

Peter Nicholson called himself an architect, carpenter, surveyor, builder, and math teacher. He learned most of his math by himself. He later used his math skills to solve problems in architecture.

He once wrote that he learned most of his math from books when he was young. He wanted to use this knowledge for practical things, so he focused on architecture.

The French Academy of Sciences praised his work on "involution and evolution" (a math topic). They wrote him a letter in 1820, thanking him for his "interesting work."

As an Architect and Builder

Even though he was a great mathematician, Peter Nicholson is mostly remembered as an architect. A historian named Howard M. Colvin said that Nicholson was "one of the leading thinkers behind nineteenth-century building technology." He used his math skills to make old architectural formulas simpler and to create new ones.

Colvin also said that Peter's writings were not just about theory. They helped real builders and craftsmen solve problems. For example, his improvements to handrail construction and his invention of the centrolinead helped create the beautiful curved staircases seen in buildings from the late Georgian period.

His Work on the Skew Arch

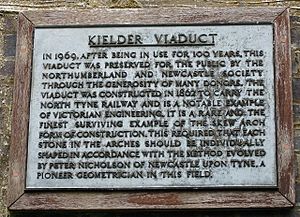

Peter Nicholson received many thank-you letters from builders and engineers for his work on the skew arch. He published these letters in his book Guide to Railway Masonry. The Kielder Viaduct, a bridge with seven arches built using his ideas, has a plaque remembering his important work.

One builder, James Hogg, wrote that Nicholson's book was the most useful way to build an oblique arch. He said that with Nicholson's method, building these arches became almost as simple as building a regular arch.

Other engineers, like Charles Fox and George W. Buck, also recognized Nicholson's important contributions. They built on his ideas, even if they sometimes offered their own improvements.

Sadly, some of these discussions turned into arguments. Peter, who was in his 70s and not well, was upset by some of the harsh comments.

How People Saw Him

The people of Newcastle thought very highly of Peter Nicholson. They felt it was unfair that he was struggling financially. They sent a petition to the king asking for a pension for him.

The petition said that Peter Nicholson's work helped British mechanics become better than those in other parts of Europe. It also said that even though his work was praised by many learned societies, he didn't get enough money to live comfortably. They felt it was sad that someone who dedicated his life to science was left in poverty in his old age.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |