Plutarco Elías Calles facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Plutarco Elías Calles

|

|

|---|---|

Plutarco Elías Calles, c. 1924-28

|

|

| 47th President of Mexico | |

| In office 1 December 1924 – 30 November 1928 |

|

| Preceded by | Álvaro Obregón |

| Succeeded by | Emilio Portes Gil |

| 2nd Governor of Sonora | |

| In office 1915–1919 |

|

| Preceded by | José María Maytorena |

| Succeeded by | Adolfo de la Huerta |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Francisco Plutarco Elías Campuzano

25 September 1877 Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico |

| Died | 19 October 1945 (aged 68) Mexico City, D.F., Mexico |

| Resting place | Monument to the Revolution Spanish: Monumento a la Revolución |

| Political party | National Revolutionary Party Laborist Party (until 1929) |

| Spouse |

Natalia Chacón Amarillas

(m. 1899; died 1927)Leonor Llorente

(m. 1930; died 1932) |

| Parents |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1914–1920 |

Plutarco Elías Calles (born September 25, 1877 – died October 19, 1945) was a brave general during the Mexican Revolution. He was also a politician from the state of Sonora. He served as the President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928.

His 1924 presidential campaign was special because it was the first "populist" one in Mexico. This means he promised to help ordinary people. He wanted to give land to farmers, make sure everyone had fair justice, improve education, and protect workers' rights. He also aimed for a more democratic government.

After his first two years, Calles focused on separating the church from the government. He passed laws that limited the power of the Roman Catholic Church. This led to a big conflict called the Cristero War.

Calles is most famous for starting the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in 1929. This party brought political stability to Mexico after the president-elect, Alvaro Obregón, was assassinated in 1928. The party, or its later versions, ruled Mexico for a very long time, from 1929 until 1997, and then again from 2012 to 2018. Even after his presidency, Calles still had a lot of influence in Mexican politics. This period was known as the Maximato. His influence lasted until Lázaro Cárdenas became president in 1934. Calles is buried in the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City.

Contents

Early Life and Start in Politics

Plutarco Elías Calles was born Francisco Plutarco Elías Campuzano. His parents, Plutarco Elías Lucero and María Jesús Campuzano Noriega, were not married. He later took the last name Calles from his aunt's husband, Juan Bautista Calles. This uncle and his wife raised Plutarco after his mother passed away.

His uncle was a small shop owner and an atheist. He taught young Plutarco to believe in education that was separate from religion. He also taught him to question the power of the Roman Catholic Church. These ideas later shaped Calles's plans to expand public education and reduce the Church's influence in government and schools.

Calles's father's family was well-known in northern Mexico. They were involved in wars against native groups like the Yaqui and Apache. Plutarco's father lost his own father in 1865 during a fight against the French. This left his family with financial difficulties.

Historians believe that Calles's tough childhood made him very hardworking and determined. He wanted to overcome challenges and help his family. He felt that denying the Church's authority was a way to deal with the fact that his parents were not married.

As a young man, Calles worked many different jobs. He was a bartender and a schoolteacher. He was always looking for chances to get involved in politics.

Before Becoming President

Joining the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917)

Calles supported Francisco I. Madero, an early leader of the Revolution. He became a police commissioner under Madero. Calles was good at joining forces with the winning side, the Constitutionalists, led by Venustiano Carranza. This helped him quickly rise through the ranks. By 1915, he became a general.

He led the Constitutional Army in his home state of Sonora. In 1915, his forces stopped the armies of José María Maytorena and Pancho Villa in the Second Battle of Agua Prieta.

Governor of Sonora

Calles became the governor of Sonora in 1915. He worked to make many practical changes. He wanted to help Mexico's economy grow quickly. He also helped build important roads and other structures.

He tried to make Sonora a "dry state," meaning alcohol sales were tightly controlled. He also pushed for better education. He passed laws to give workers social security and the right to form unions.

Working for President Carranza

In 1919, Calles moved to Mexico City. He became the Secretary of Industry, Commerce, and Labor for President Venustiano Carranza. This job put him in charge of Mexico's economy, which was badly damaged by the Revolution.

Mines and farms were struggling. Railways, which connected cities and businesses, were broken. There was also a shortage of money, and many people used U.S. dollars instead. Calles gained valuable experience in this role. He also earned the support of workers by helping to solve a labor dispute.

Overthrowing Carranza (1920)

In 1920, Calles joined other generals from Sonora, Adolfo de la Huerta and Álvaro Obregón. They decided to overthrow Carranza. Carranza had tried to choose someone unknown as his successor. Carranza was forced out of power and died while trying to escape.

De la Huerta became the temporary president. He then made Calles the important Minister of War.

Obregón's Presidency and the 1924 Election

Obregón was elected president in 1920. He appointed Calles as his Secretary of the Interior. During Obregón's time as president (1920–1924), Calles became close with labor unions. These included the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers (CROM) and the Laborist Party. He also supported agraristas, who were radical farmers wanting land reform.

A serious military conflict happened, but Obregón won with support from the U.S. The U.S. helped Obregón after Mexico agreed to protect U.S. business interests, especially oil, in the Bucareli Treaty of 1923.

Calles's campaign for president was supported by labor and farmer unions. The Laborist Party, which backed him, was closely linked to the powerful CROM union. Luis N. Morones, the head of CROM, was a well-known labor leader. He had even worked with Samuel Gompers, a U.S. labor leader. CROM's support was very important for Calles to win the election.

In 1924, Calles won the election and became president.

Before he officially became president, Calles traveled to Germany and France. He wanted to learn about how social democracy and labor movements worked there. This trip gave him new ideas beyond Mexico. He was impressed by Germany's industries and strong labor unions. He also saw how powerful speeches could gain public support.

Presidency (1924–1928)

Calles's inauguration as president was a huge event. About 50,000 people watched. It was the first time in many years that a president peacefully handed over power to another. Workers from the CROM union showed their support with banners.

Even as president, Calles was still somewhat in the shadow of Obregón. Obregón had strong allies in the military and government. Many thought Calles was just a temporary president who would give power back to Obregón later. But Calles wanted to build his own power. He started a reform program similar to what he did in Sonora. He aimed to boost the economy, make the army more professional, and improve social welfare and education. He relied on workers and farmers to support him.

Supporting Workers

Luis Morones, the head of the CROM union, became the Secretary of Industry, Commerce, and Labor. This allowed him to help his union grow and become more powerful. Calles worked to put Article 123 of the Mexican Constitution into action. This article protected workers' rights. Wages increased, and working conditions got better.

There were fewer labor strikes during Calles's time. However, when railway workers went on strike in 1926, Morones sent other workers to break the strike.

Managing Mexico's Money

Calles relied on his Secretary of the Treasury, Alberto J. Pani, to handle Mexico's finances. Pani's policies helped restore trust from foreign investors. He balanced the government's budget and kept the currency stable. Pani also helped create several banks to support farmers. Most importantly, he helped establish the Banco de México, Mexico's national bank. Pani also managed to reduce some of Mexico's foreign debt.

Reforming the Military

The military was very expensive, using a third of the national budget. Many generals had gained their rank during battles. Calles wanted to make the army more professional and reduce its cost. He put Joaquín Amaro in charge of these changes.

New laws required officers to have professional training to get promoted. The government also tried to reduce corruption by punishing it severely. There was also a mandatory retirement age for officers. The military academy, Colegio Militar, was improved to train better officers.

Building Infrastructure

Railroads were important for the economy and controlling distant areas. The Revolution had damaged many railways, so rebuilding was ongoing. Calles privatized the railways and built a new line connecting his home state of Sonora to Mexico City.

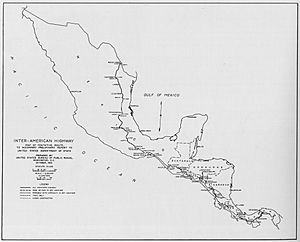

Even more important, Calles started a huge project to build a network of roads across Mexico. This network would connect major cities and small villages. He created the National Road Commission. He believed roads would help farmers get their crops to market more easily. They would also help the government reach more remote communities. This project helped connect different parts of the country. It linked people to national politics, economy, and culture. Work began on the Mexican section of the Pan-American Highway. This highway would link Nuevo Laredo to Tapachula, near the Guatemala border. Road building was paid for by a gasoline tax.

Improving Education

Education was also important to Calles. He put more government money into rural education. He added two thousand new schools to the thousand already built by the previous president. A main goal of rural education was to help Mexico's native people become part of the nation. So, teaching Spanish was a key part of public education.

The aim was to create loyal and patriotic citizens. The Secretary of Education developed materials that praised the achievements of Obregón and Calles.

Public Health Efforts

Public health in Mexico was not good after the Revolution. Calles wanted to improve health and hygiene because healthy citizens were important for economic growth. He created a special government department for public health.

This department promoted vaccinations against diseases. It also worked to improve access to clean drinking water, sewage systems, and inspected restaurants. A new law in 1926 made vaccinations mandatory. It also gave the government power to improve sanitation and hygiene.

Changes to Civil Law

Calles changed Mexico's civil laws to give children born to unmarried parents the same rights as those born to married parents. He did this partly because of his own childhood experiences.

Another important law was the Law of Electrical Communications (1926). This law said that radio airwaves belonged to the government. Radio stations had to follow government rules. They could not broadcast religious or political messages without permission. They also had to broadcast government announcements for free. This law showed the government's growing power.

Oil and U.S.-Mexico Relations

Oil was a big issue between Mexico and the U.S. Calles quickly rejected the Bucareli Treaty of 1923. This treaty was made when Obregón was president. Calles started writing a new oil law that would strictly follow Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution.

Article 27 said that everything under the soil belonged to the state. This worried U.S. and European oil companies, especially if the law applied to oil fields they already owned. A Mexican Supreme Court decision had said that foreign-owned fields could not be taken if they were already operating before the constitution. The Bucareli Agreements had said Mexico would respect this court decision if the U.S. officially recognized Obregón's presidency.

The U.S. government reacted strongly to Calles's plans. The U.S. ambassador called Calles a communist. The U.S. Secretary of State even threatened Mexico in 1925. Calles did not see himself as a communist. He saw revolution as a way to govern. Some in the U.S. government started calling Mexico "Soviet Mexico." This happened after the Soviet Union opened its first embassy in any country in Mexico.

The new oil law was passed in 1926. In 1927, Mexico canceled permits for oil companies that did not follow the law. There was talk of war from the U.S. president and in newspapers. But Mexico avoided war through diplomacy. A direct phone line was set up between Calles and U.S. President Calvin Coolidge. The U.S. ambassador was replaced by Dwight Morrow. Morrow helped Mexico and the oil companies reach an agreement.

Another conflict with the U.S. was Mexico's support for liberals in the civil war in Nicaragua. The U.S. supported the other side. This conflict ended when both countries signed a treaty.

Conflict with the Church

In the first two years of his presidency, Calles made reforms that helped workers and farmers. But in his later years, he caused a major conflict with the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico. Calles did not believe in the Church's freedom to organize.

He enforced the anti-church parts of the Constitution of 1917. This led to a violent and long conflict called the Cristero Rebellion, or the Cristero War. The government took strong actions against the clergy. The conflict ended in 1929 with help from U.S. Ambassador Dwight Morrow.

On June 14, 1926, President Calles passed a law known as the Calles Law. This law outlawed religious orders and aimed to reduce the Church's influence. In response, the Catholic Church stopped celebrating Mass, baptizing children, and performing other religious services for three years.

Because Calles strictly enforced these anti-church laws, people in strong Catholic areas began to oppose him. On January 1, 1927, many Catholics shouted, "¡Viva Cristo Rey!" (Long live Christ the King!).

Almost 100,000 people died on both sides in the war. A truce was made with help from Ambassador Dwight Morrow. The Cristeros agreed to stop fighting. After the truce, Calles insisted that the government control all education. He wanted to replace Catholic education with secular education. He said, "We must enter and take possession of the consciences of the children... because they do belong, and should belong to the revolution."

Between 1926 and 1934, at least 4,000 priests were killed or forced to leave Mexico. By 1935, seventeen states had no priests at all.

This conflict weakened Calles politically. This weakness helped Alvaro Obregón return to the presidency in the 1928 election.

1928 Election

Obregón ran for president in 1928 without any opponents. He was able to run again even though he had been president before. This was because Calles's government had changed the constitution in 1926 to allow a president to be re-elected after a break. This rule was later changed back in 1934. Also, in 1927, Mexico changed the constitution to make a presidential term six years instead of four. Obregón was elected as Calles's successor.

After the Presidency

Founding a New Party and the Maximato (1929–1934)

President-elect Obregón was killed by a Catholic activist before he could take office. Calles could not become president again. So, he worked to prevent a power vacuum. Emilio Portes Gil was appointed temporary president. Calles then created a new political party, the National Revolutionary Party (PNR). This party is now known as the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

The period from 1928 to 1934 is known as the Maximato. During this time, Calles was seen as the "Maximum Chief" (Jefe Máximo). He was the real power behind the presidents, even though he never used that title himself. Many people saw Emilio Portes Gil, Pascual Ortiz Rubio, and Abelardo Rodríguez as presidents who followed Calles's orders. Officially, after 1929, Calles served as Minister of War. He continued to fight corruption. A few months later, with help from U.S. Ambassador Dwight Morrow, the Mexican government and the Cristeros signed a peace treaty. During the Maximato, Calles also served as Minister of Industry and Commerce.

By 1933, two of Calles's former military officers, Manuel Pérez Treviño and Lázaro Cárdenas, had risen in the party. Calles supported Cárdenas to be the PNR's presidential candidate in the 1934 election. By this time, the PNR was so strong that Cárdenas's victory was almost certain. He won with nearly 98 percent of the votes.

End of the Maximato and Exile

Cárdenas had worked with Calles for over twenty years. Calles and his allies trusted Cárdenas. They believed he would work with Calles as previous presidents had. But Cárdenas soon showed he was independent. Conflicts arose between Calles and Cárdenas. Calles did not like Cárdenas's support for labor unions and strikes. Cárdenas disagreed with Calles's views.

Cárdenas began to remove Calles's supporters from political jobs. He sent many of Calles's allies into exile. Finally, Calles himself was arrested along with Luis N. Morones, the head of the CROM union. They were accused of planning to blow up a railroad. These were false accusations, used to exile Calles.

Calles was deported to the United States on April 9, 1936. His son Alfredo and his secretary were also exiled. In exile, Calles lived in San Diego with his family. He even became friends with José Vasconcelos, a Mexican philosopher who had been his political enemy.

Return from Exile and Final Years

The Institutional Revolutionary Party was now firmly in control. To promote national unity, President Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940–1946) allowed Calles to return to Mexico in 1941. He spent his last years quietly in Mexico City and Cuernavaca.

Back in Mexico, Calles's political views became more moderate. In 1942, he supported Mexico's decision to declare war on the Axis powers during World War II. He also became interested in spiritualism and came to believe in a "Supreme Being."

Personal Life

Calles married Natalia Chacón (1879–1927), and they had 12 children. Some of their children included Rodolfo Elías Calles (who became governor of Sonora) and Plutarco Elías Calles Chacón (who became governor of Nuevo León).

After Natalia's death in 1927, Calles married Leonor Llorente in 1930. Leonor died in 1932 at age 29. Calles himself had health problems throughout his life, including a rheumatic illness and stomach issues. The death of his first wife was a very difficult time for him.

Legacy

Calles's most important legacy was bringing peace to Mexico. He ended the violent period of the Mexican Revolution by creating the National Revolutionary Party (PNR). This party, now known as the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), governed Mexico for many decades.

Calles's legacy is still debated today. However, within the PRI, his importance has been recognized more over time. His remains were moved to the Monument to the Revolution. He is buried there alongside other important figures like Madero, Carranza, Villa, and Cárdenas, who were his political rivals. For many years, Cárdenas's presidency was seen as the true spirit of the Revolution. But now, Calles is also recognized as the founder of the party that brought political stability to Mexico.

In 1990, a monument to Calles was built. It honors his speech from September 1928, where he declared the end of the era of caudillos (strong military leaders). This speech was given after Obregón's assassination. It showed how the party Calles created would solve the problem of violent presidential successions.

He has statues in Sonoyta, Hermosillo, and his hometown of Guaymas. The municipality of Sonoyta is officially named Plutarco Elías Calles Municipality in his honor.

Because of his actions against the Church, Calles was criticized by Pope Pius XI. The Pope called his actions "unjust" and "hateful" in an official letter.

See also

In Spanish: Plutarco Elías Calles para niños

In Spanish: Plutarco Elías Calles para niños

- List of heads of state of Mexico

- History of democracy in Mexico

- Mexican Revolution

- Sonora in the Mexican Revolution

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |