Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument facts for kids

The Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument is a special memorial located in Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn, New York City. It honors over 11,500 American prisoners of war who died on British prison ships during the American Revolutionary War. These ships were docked in New York Harbor. The monument stands over a crypt where some of their remains are buried. Some of the ships included HMS Jersey, Scorpion, and Hope.

The remains of these brave soldiers were first collected in 1808. Later, in 1867, famous landscape designers Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux created a new plan for Washington Park (now Fort Greene Park). They also designed a new crypt for the remains. In 1873, more remains were found near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. They were moved to a new crypt under a smaller monument. People then raised money for a much larger monument.

This grand monument was designed by the well-known architect Stanford White. It is made of granite and has a tall Doric column that is about 149 feet (45 meters) high. It sits on top of a wide staircase with 33 steps. At the very top of the column is a huge, eight-ton bronze brazier, which is like a large funeral urn. This urn was made by sculptor Adolph Alexander Weinman. The monument was officially opened in 1908. William Howard Taft, who was about to become president, gave the main speech.

Contents

Why We Remember: The Story of the Prisoners

Terrible Conditions for War Prisoners

During the Revolutionary War, the British kept American prisoners of war on ships in New York Harbor. They also held them in jails on land. Life on these prison ships was extremely harsh. Many more Americans died in these British jails and prison ships than in all the battles of the American Revolutionary War.

When prisoners died, the British either quickly buried their bodies or threw them into the water. After the war ended in 1783, the remains of those who died on the prison ships were left along the Brooklyn shore. This area was called Wallabout Bay. In 1877, the New York Times newspaper reported that these dead soldiers came from every state in the new nation.

Local church officials tried to move the bones, but the landowner refused. People described seeing "skulls and feet, arms and legs sticking out of the crumbling bank." One person said the skulls on the coast were "as thick as pumpkins." When workers built the Naval Yards, they found many bones. They collected them in barrels and boxes. These bones were then reburied on the nearby John Jackson estate.

Eventually, many barrels full of bones were collected. The monument's dedication plaque says that 11,500 prisoners died on the ships. However, some people believe the number could be as high as 18,000.

How the Memorial Idea Grew

The idea to honor these fallen soldiers became popular when political groups started to disagree more. The Democratic-Republicans wanted a memorial. This was partly in response to the Federalists building a statue of George Washington in 1803.

The Tammany Society, a Republican group, was formed. In 1803, Republican Congressman Samuel L. Mitchill asked the government to build a monument, but it didn't happen. So, they decided to focus on a big ceremony to rebury the prisoners' remains. They wanted something that felt right for everyday people.

In 1808, the Tammany Society formed the Wallabout Committee. Their efforts gained strength because of new anti-British feelings. This was due to British actions in 1806 and 1807. When President Thomas Jefferson passed the Embargo Act in 1808, the Tammany Society used their reburial plans to increase anti-British feelings.

Early Memorials: Vaults and Monuments

The First Vault and Monument (1808)

On April 13, 1808, a ceremony was held to lay the first stone for a planned burial vault. A grand reburial ceremony followed on May 26, 1808. The state agreed to give the Tammany Society $1,000 to build a monument. However, the monument was never built.

A small square building with an eagle on its roof stood over the 1808 vault. It was located near the Brooklyn Navy Yard waterfront in an area now called Vinegar Hill. A wooden fence with 13 posts, painted with the names of the original 13 states, stood in front. An inscription at the entrance read: "Portal to the tomb of 11,500 patriot prisoners." The remains were placed in long coffins made of bluestone.

Over time, this first monument fell apart due to neglect. In 1839, Benjamin Romaine bought the land where the martyrs were buried. He later asked for support to build a proper monument. On January 31, 1844, Benjamin Romaine died. He had been a prisoner on the ships himself and was also buried in the crypt.

The Second Vault and Monument (1873)

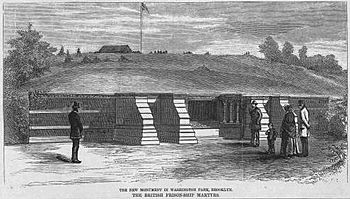

Later in the 1800s, the idea of a monument gained interest again. In 1873, $6,500 was set aside for a new mausoleum. This new brick mausoleum was built in Fort Greene Park, which was then known as Washington Park. It was decorated with pillars of polished stone.

The front of the tomb had an inscription: "SACRED TO THE MEMORY, OF OUR SAILORS, SOLDIERS AND CITIZENS, WHO SUFFERED AND DIED ON BOARD BRITISH PRISON SHIPS IN THE WALLABOUT DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION." On June 18, 1873, the bones from the first tomb were moved to this new one. The bones stayed here until enough interest and money were gathered for the current, larger monument.

The Current Monument: A Grand Tribute

Planning and Building the Monument

The Fort Greene chapter of the DAR was formed in Brooklyn in 1896. Their goal was to build a "suitable memorial" for the martyrs who died on the prison ships. They quickly teamed up with the Old Brooklynites group to focus more on the memorial.

In 1899, more bones were found in the Brooklyn Naval Yard. This renewed interest in building a major monument. On June 16, 1900, these newly found bones were buried in the crypt with full military honors. The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper reported that a committee was chosen to build a larger memorial. Thanks to this committee's work, money for a new monument was finally raised.

Money came from all levels of government. In 1902, the U.S. government set aside $100,000 for the memorial. This was on the condition that another $100,000 be raised from other sources. New York State gave $25,000, and New York City gave $50,000. Private donations provided another $25,000.

After the funds were secured, the Prison Ship Martyrs Association was created in 1903. They oversaw the project. The famous architect Stanford White was chosen to design the monument. The Carlin Construction Company built it. In 1776, Fort Greene Park was the site of Fort Putnam, a defense built to protect New York from the British.

The Dedication Ceremony

The dedication ceremony took place on November 15, 1908. It included a huge parade with 15,000 participants. These included military groups, veterans, and civic organizations. William Howard Taft, the President-elect, and other important leaders watched. About twenty thousand people came to see the event.

The enormous flag covering the monument slowly slid down. The ceremony began with a prayer. A poem was read by the poet laureate for the occasion, Thomas Walsh. Taft gave the main speech. He talked about how American prisoners were treated. He said they died because of the "cruelty of their immediate custodians and the neglect of those in higher authority."

Taft also discussed how prisoners of war were treated throughout history. He praised the recent Hague Convention. This agreement set rules for how prisoners should be treated. He mentioned the First Sino-Japanese War where both sides treated prisoners very well.

Since 1908, the Society of Old Brooklynites has held an annual memorial for the martyrs.

Taking Care of the Monument: Neglect and Repairs

1900s: Challenges and Renovations

In 1914, one of the bronze eagles from the monument was stolen. The thieves sold it for scrap metal. Police tracked them down, but the eagle's wings had already been removed and partly melted.

By 1921, the beacon light at the top of the monument was out. The spiral stairways inside the column, where visitors used to pay to climb, were closed. Visitors could no longer go to the top for views of Manhattan. In 1923, vandals damaged the bronze door to the crypt. The crypt was left open.

The New York Times reported that neighborhood children used the monument's walls as a slide. The monument became damaged and neglected. Work was done to clean and preserve the site. A staircase and elevator were installed inside the column. It reopened in 1937, thanks to Park Commissioner Robert Moses.

However, the park was neglected again, and more repairs were needed. Work began in 1948 to keep the monument from falling apart. The staircase and elevator were removed in 1949. In 1966, the eagles were removed and went missing until 1974.

By the 1970s, graffiti covered much of the monument's base. The four eagles were repaired and put back around 1974. They were removed again in 1981. Two of them are now on display at the Central Park Arsenal.

In 1995, an inspection of the vault found bone fragments in 20 slate boxes. Graffiti was also noted on the crypt's interior walls. In 2000, workers found a partially collapsed wooden coffin inside Benjamin Romaine's stone coffin. By then, the monument was missing plaques, and the eternal flame was out.

2000s: Renewed Efforts

In 2003, an archaeological dig took place at the original site of the Martyrs' Monument. This was done before new housing was built there. The dig looked for more human remains and signs of the first crypt. They found evidence of a deep space and old fence post holes.

The city began a $3.5 million renovation of the monument in 2004. The repairs faced problems and cost more than expected. A new spiral staircase was built inside the memorial.

The restored monument was unveiled on November 15, 2008. This was a celebration of its 100th anniversary. More than 500 people gathered to see the flame relit. The monument was lit up beautifully that night. The total cost for the restoration from 2006 to 2008 was about $5.1 million. However, in 2009, the light stopped working again. The parks department fixed it, explaining it was a timer issue.

In April 2015, a group of anonymous people secretly placed a statue of Edward Snowden on one of the columns. Park staff removed it the same day.

What the Monument Looks Like

The monument is made of granite. Its single Doric column is about 149 feet (45 meters) tall. It sits above the crypt at the top of a wide staircase with 99 steps. When it was built, it was the tallest Doric column in the world. The column has the inscription: "1776 THE PRISON SHIP MARTYRS MONUMENT 1908."

The column used to have a staircase inside, accessed by a bronze door. The stone for the monument came from a quarry in Vermont. The grand staircase has 100 granite steps and rises in three sections. At the bottom of the staircase, the entrance to the vault was covered by a stone slab. This slab is now in storage. It lists the names of the 1808 monument committee and builders. It also has an inscription about the "spirits of the departed free."

At the top of the column are lion's heads. These heads weigh over 100 pounds (45 kg) each. They hold up the huge, eight-ton bronze brazier, or funeral urn. The urn is 22.5 feet (6.8 meters) tall. It was made by the Whale Creek Iron Works. The top of the urn has thick glass. Inside are the lights for the "eternal flame." This flame went out in 1921. It was relit in 1997 with new solar-powered lights that reflect from a mirror. It is now lit every night. A bronze railing surrounds the urn.

Four large, open-winged bronze eagles, each weighing 300 pounds (136 kg), once stood at the corners of the terrace at the column's base. They were designed by Adolph Alexander Weinman, who also designed the urn.

The crypt is a vault at the base of the stairs. Inside, the floor is concrete, and the walls and ceiling are brick. You enter through a copper-covered door. The crypt is about 15 to 20 feet (4.5 to 6 meters) square. It has slate coffins on shelves. Different types of bones are said to be sorted into different coffins. This is because individual bodies could not be identified.

Added Features and Information

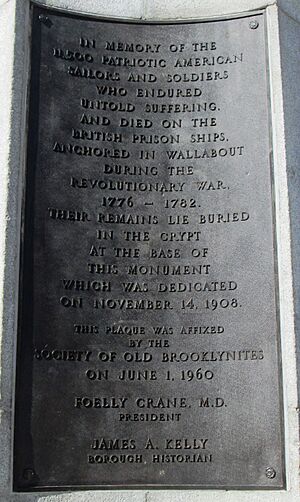

In 1960, a plaque was added to the monument. It reads: "In memory of the 11,500 patriotic American sailors and soldiers who endured untold suffering and died on the British prison ships... Their remains lie buried in the crypt... This plaque was affixed by The Society of Old Brooklynites on June 1, 1960."

In 1976, during the United States Bicentennial (200th anniversary of the U.S.), King Juan Carlos of Spain dedicated a plaque. It honored the 700 Spaniards who died on the prison ships.

Today, there are exhibits around the monument. They explain the history of the prison ships, the Battle of Brooklyn, and list the names of 8,000 known martyrs.

Near the monument, there is a small building that used to be restrooms. It is now a visitors' center for the park. The center has pictures and displays of Revolutionary War weapons and uniform buttons found in the park. It also has a list of 8,000 known prisoners from British records.

Who Takes Care of the Monument?

In the early 1900s, people tried to get the monument recognized as a national site. However, the U.S. Department of the Interior said no. They noted that the prisoners did not die at the monument's exact location.

Currently, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation is in charge of keeping the monument preserved and supervised. From 2006 to 2008, electrical improvements cost about $341,000. The total restoration cost for the monument during that period was estimated at $5.1 million.

In 2013, U.S. Congressman Hakeem Jeffries suggested a law to study if the monument should become part of the National Park System. This study would look at the costs and effects of such a designation. The House of Representatives voted to pass the bill in 2014. The Department of the Interior supported the bill.

The National Park Service said the monument "commemorates the sacrifice over more than 11,000 patriots during the American Revolution." Representative Yvette Clarke said the monument reminds us that "even in wartime we must protect basic human rights." Representative Jeffries added that the monument "deserves to be considered as a unit of the National Park Service."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Monumento a los mártires de barcos para prisioneros para niños