Protestation of 1641 facts for kids

The Protestation of 1641 was an important attempt to stop the English Civil War from happening. In May 1641, the Parliament made a new rule. Everyone over 18 had to sign an oath called the Protestation.

This oath was a promise to be loyal to King Charles I and the Church of England. The idea was to calm down the big disagreements happening in England. If you wanted to work in public office, you had to sign it. People who refused to sign were also noted down.

At this time, England was full of worry. There were many quick changes in politics, religion, and society. People in Parliament and those loyal to the King wanted to avoid a fight. They tried using loyalty oaths like the Protestation. It started in May 1641. The goal was for all English men over 18 to promise to defend King Charles I and the Church of England.

Sadly, the Protestation didn't work. The disagreements between Parliament and King Charles I grew worse. This led to the start of the English Civil Wars in August 1642. Still, the Protestation helps us understand how people tried to stop a very costly war. It shows us the steps that led to the English Civil Wars.

The Protestation is an interesting part of history. It helps us see how people tried to avoid a bloody conflict. This attempt happened three times before the civil wars began. The English Civil Wars changed England forever. They led to King Charles I being executed. For a while, there was no king, and Oliver Cromwell ruled. Later, the king returned with Charles II during the English Restoration. This shows how complicated and worrying those times were in Stuart England.

Contents

Why the Protestation Happened: The Background Story

The Protestation came about because of big problems in England. These problems were both about religion and politics.

Religious Changes and Worries

The 1500s and 1600s were a time of huge religious changes. The Protestant Reformation began in 1517 with Martin Luther. This movement started to end the power of the Catholic Church in Western Europe. In England, Henry VIII made many changes. He broke away from the Pope in 1534 with the Act of Supremacy. This made the King the head of the Church of England.

However, many English people were still Catholic. This caused a lot of tension and worry. By 1641, many Protestants feared that their religion was in danger. They worried about Catholic influence around King Charles I. So, the Long Parliament was asked by the King to create a national declaration. This was meant to calm religious tensions.

This declaration became the Protestation of 1641. It was the first of three loyalty oaths made by the Long Parliament. The others were the Vow and Covenant and the Solemn League and Covenant. Many Protestants were also unhappy with Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud. He wanted to make the Church of England more ceremonial. This led to conflicts between the Church of England and Puritans.

Political Problems with King Charles I

King Charles I had been ruling without Parliament for a long time. This was called his Personal Rule. But he needed money for an army. He had to fight the Covenanters in Scotland during the Second Bishops' War. He also needed to stop revolts in Ireland. So, he had to call Parliament.

The House of Commons and the House of Lords, led by John Pym, didn't want to give him money. Instead, they complained about the government. Charles saw this as an attack on his power. He quickly closed this Parliament, which became known as the Short Parliament.

Charles decided to fight Scotland without Parliament's help. He called Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford back from Ireland. Strafford had managed to control the Irish revolt. He convinced Catholic nobles to pay taxes for future religious benefits. This helped Charles I get more money and calm Ireland.

But Strafford failed in battle. Charles I also ran out of money because of the armies. So, he listened to his advisors and called Parliament again. He needed more taxes to fight the Scottish rebellion. This new Parliament was called the Long Parliament. It met for twenty years, from 1640 to 1660.

The Long Parliament was even more against Charles I than the Short Parliament. John Pym led it again. They started passing laws to limit the King's power. For example, they said the King couldn't tax people without Parliament's approval. They also wanted control over the King's ministers. Even though they were against Charles I, they still tried to avoid a war. The Protestation was their first attempt to stop the conflict from becoming a costly civil war.

The Protestation: What It Was and How It Worked

People were scared that the Protestant religion was in danger. They especially worried about Catholic influence around King Charles I. So, a group of ten men from the House of Commons was chosen. Their job was to write a national declaration. This became the first oath of loyalty to King Charles I and to the Protestant Church of England.

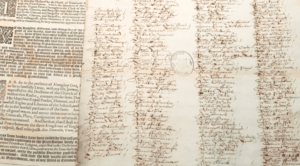

The oath was written on May 3, 1641. Parliament quickly approved it. All members of the House of Commons signed it. The next day, members of the House of Lords signed too. Then, letters were sent to the sheriffs of every Parish (local area). These letters told them about the decision. Sheriffs and Judges of Peace had to sign the oath as well.

The final step was for sheriffs and Judges of Peace to read the oath in church. Everyone present had to sign it. People were required to go to church every Sunday or pay a fine. So, almost everyone was expected to sign. If someone refused to sign, their name was still written down. They were then not allowed to hold public office. This process continued until February and March 1642.

The oath that people had to swear was this:

"I, _ A.B. _ do, in the presence of Almighty God, promise, vow, and protest to maintain, and defend as far as lawfully I may, with my Life, Power and Estate, the true Reformed Protestant religion, expressed in the Doctrine of the Church of England, against all Popery and Popish Innovations, within this Realm, contrary to the same Doctrine, and according to the duty of my Allegiance, to His Majesties Royal Person, Honour and Estate, as also the Power and Privileges of Parliament, the lawful Rights and Liberties of the Subjects, and any person that maketh this Protestation, in whatsoever he shall do in the lawful Pursuance of the same: and to my power, and as far as lawfully I may, I will oppose and by all good Ways and Means endeavour to bring to condign Punishment all such as shall, either by Force, Practice, Councels, Plots, Conspiracies, or otherwise, doe any thing to the contrary of any thing in this present Protestation contained: and further, that I shall, in all just and honourable ways, endeavour to preserve the Union and Peace betwixt the Three Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland: and neither for Hope, Fear, nor other Respect, shell relinquish this Promise, Vow and Protestation."

The hope was that by making all English men over 18 sign this oath, they would unite. They would support King Charles I and avoid a bloody internal conflict.

However, on January 18, 1642, things got worse. King Charles I tried to arrest five important members of Parliament. These were known as the Five Members. After this, the speaker of the House of Commons, William Lenthall, sent another letter. He demanded that all men over 18 take the oath. Lenthall thought that those who refused would be Catholics. This would make them unfit for jobs in the Church or State. It would also help find people who supported King Charles I.

But this wasn't a good way to find Catholics. Some Catholics signed the oath even with their faith. Also, some Protestants refused to sign it. The lists of signatures were sent back to Parliament later in 1642. These are known as the Protestation Returns.

In the end, the Protestation failed. If it had worked, the next two oaths wouldn't have been needed. It didn't unite the country under Charles I. It also didn't stop the civil war, which started soon after. Finally, it didn't help Parliament tell Catholics from Protestants. Many people signed the list, but there were still many known Catholics.

Instead of stopping conflict, the Protestation sometimes made it worse. For example, when Speaker Lenthall demanded everyone sign after Charles I tried to arrest the Five Members. However, these lists have been very useful for historians. They act as a partial count of the population. They help estimate how many people lived then. They are also important for people looking for ancestors from before the English Civil Wars. And they help academics study how last names were spread out before the wars.

What Happened Next: The Aftermath

After the 1641 Protestation failed, Parliament tried two more times. They tried to create loyalty oaths to King Charles and the Church of England. But these also failed.

The Long Parliament then focused on Thomas Wentworth, the Earl of Strafford. They accused him of betraying the country. King Charles I loved Strafford and didn't want him punished. But John Pym found notes from the King's private meetings. In these notes, Strafford said King Charles I could use his army from Ireland to stop any revolts. This was because his subjects had failed him.

Soon after, Pym suggested a Bill of Attainder for Strafford. This was a special law to execute him. After some debate, the House of Commons and the House of Lords approved it on April 21, 1641. Charles I didn't want to sign it. Without his signature, Strafford would be safe. But on May 10, Charles I signed it, fearing for his family's safety. Strafford was executed two days later.

People hoped that Strafford's execution and the Protestation would calm things down. But the opposite happened. In May 1641, the Long Parliament passed the Triennial Acts. These laws demanded that Parliament meet at least every three years. This was true even if the King didn't call them. They also stopped the King from raising money without Parliament's approval. This included taxes like Charles I's Ship Tax.

At this time, Parliament still blamed the King's bad advisors, not the King himself. But as conflicts grew, both sides became suspicious. Parliament thought Charles I wanted to force his religious ideas on them. They also feared he would use military force. Charles and his supporters felt Parliament was constantly making demands. They saw this as going against the King's power.

Neither side could push the conflict further right away. This was because the Irish rebelled. They feared that Protestantism would be forced on their Catholic land. Ireland fell into chaos. Soon, rumors spread that Charles I was supporting the Irish rebels. People worried he would turn against the Puritans, just as Strafford had suggested. This caused panic among the Puritans.

Charles I tried to end his problems with Parliament once and for all. On January 4, 1642, he marched into Parliament with 400 soldiers. He planned to arrest the Five Members of Parliament. These were the leaders behind Parliament's demands. But they had already fled. When Charles asked the Speaker of the House of Commons where they were, William Lenthall replied. He said he was a servant of Parliament and would not answer the King.

Just a few days later, Charles I left London for the countryside for his safety. Cities and towns then declared their support for either the King or Parliament. Most of England, however, stayed neutral. As summer came, talks between the King and Parliament failed. The situation remained stuck.

On August 22, 1642, Charles I raised his Royal Standard. This was a sign that war had finally begun. On one side were the Cavaliers, or Loyalists. They supported the Church of England and wanted to keep the traditional government with the King in charge. On the other side were the Parliamentarians, or Roundheads. They were Puritans who wanted to defend what they saw as the traditional Church and State. They felt Charles had changed things unfairly during his 11 years of personal rule.

What followed were nine years of civil wars, from 1642 to 1651. The first war ended when Charles I was captured by Parliament. He was put on trial. After the trial of Charles I, he was executed for treason in 1649. The kingship was replaced by Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth of England.

Looking back, it's clear the Protestation failed. It was always going to fail. But for the people at the time, who didn't know the future, the Protestation was a real attempt to avoid a very costly civil war.

Sources

- Carlton, Charles, Archbishop William Laud, London: Routledge and Keagan Paul, 1987.

- Carlton, Charles, Charles I: The Personal Monarch, Great Britain: Routledge, 1995.

- Coward, Barry, The Stuart Age, London: Longman, 1994.

- Coward, Barry, The Stuart age: England, 1603–1714, Harlow: Pearson Education, 2003.

- Gardiner, Samuel Rawson, History of England from the Accession of James I to the Outbreak of the Civil war 1603–1642, Vol.9 1883. Cambridge, 2011

- Kelsey (2003). "The Trial of Charles I". English Historical Review. 118 (447): 583–616. doi:10.1093/ehr/118.477.583.

- Purkiss, Diane, The English Civil War: A People's History, London: Harper Perennial, 2007.

- Sherwood, Roy Edward, Oliver Cromwell: King In All But Name, 1653–1658, New York: St Martin's Press, 1997.

- Vallance,E., Revolutionary England and the National Covenant: State Oaths, Protestantism, and the Political Nation, 1553–1682. 2005.

- Walter, John, Understanding Popular Violence in the English Revolution: The Colchester Plunderers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Wedgwood, C. V., The King's War: 1641–1647, London: Fontana, 1970.

- Whiteman, Anne The Protestation Returns of 1641–1642’. Local Population Studies, 60. 1995.

- Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Fifth Report of The Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. Part I, Appendix 3

- "The Protestation Oath of 1641". Cornwall OPC Database. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

See also

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |