R v Bonjon facts for kids

R v Bonjon was an important court case in early Australian history. It took place in the Supreme Court of New South Wales for the District of Port Phillip on 16 September 1841. The case involved Bonjon, an Aboriginal man, who was accused of causing the death of another Aboriginal man, Yammowing.

The main question in the case was whether British colonial courts had the power, called jurisdiction, to judge crimes committed by one Aboriginal person against another. Judge Willis, who was in charge of the case, thought deeply about how Britain took control of Australia. He also considered what this meant for the Aboriginal people.

Even though he didn't make a final decision, Judge Willis strongly doubted that his court had the right to hear the case. The trial was allowed to start, but the lawyers for the government eventually stopped the case. Bonjon was then set free.

For a long time, this case was mostly forgotten. But more recently, people have realized how important Judge Willis's ideas were. Some experts even compare it to the famous 1992 Mabo case. The Bonjon case explored similar ideas about Indigenous rights, but 150 years earlier.

Contents

Understanding the Case: R v Bonjon

Who Were Bonjon and Yammowing?

The person accused, Bonjon (sometimes called "Bon Jon"), was an Aboriginal man from the Wathaurong people. A missionary named Francis Tuckfield, who was a witness, said that Bonjon had spent more time with Europeans than other Wathaurong people. He had even been a volunteer with the Native Police for about seven months. During this time, he helped track horses and assisted others.

The person who died, Yammowing, was from the Gulidjan people. Their land was next to the Wathaurong territory. Tuckfield knew Yammowing well because he had lived among the Gulidjan people at times.

What Happened in Geelong?

The prosecution, which is the government's legal team, claimed that Bonjon shot Yammowing around 14 July 1841. This happened in Geelong. At that time, Geelong was part of the Port Phillip District. This district was within the larger colony of New South Wales.

Because of this, the case was handled by the Supreme Court of New South Wales for the District of Port Phillip. Judge Willis heard the case in Melbourne on 16 September 1841.

Legal Arguments in the Court Case

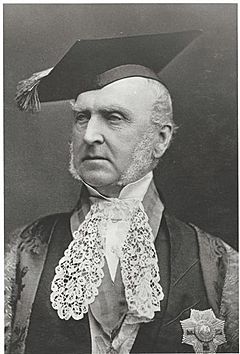

Bonjon was represented by a lawyer named Redmond Barry. The government's lawyer, called the Crown Prosecutor, was James Croke.

Could Bonjon Understand the Court?

One of the first things the court had to figure out was if Bonjon could understand the legal process. They needed to know if he could understand the charges against him. They also needed to know if he could say if he was guilty or not guilty.

Several people were called to speak about Bonjon's understanding. George Augustus Robinson, the Chief Protector of Aborigines, said he knew about Aboriginal customs. However, he didn't know Bonjon personally.

Francis Tuckfield, the missionary, then spoke. He said Bonjon had some ideas about a "Supreme Being." But his ideas were "very imperfect." Tuckfield didn't think Bonjon could understand the legal details of the case. However, he believed Bonjon could say if he was guilty or not guilty.

When asked by the government lawyer, Tuckfield said that Aboriginal people considered causing death a crime. But he added there were "some exceptions" depending on the situation.

The last witness was Foster Fyans, a police magistrate. He talked about Bonjon's time with the Native Police. Fyans said Bonjon was "particularly sharp and intelligent in his own way." But he couldn't speak English very well.

The jury decided that Bonjon couldn't understand the legal details of the case. They also felt he couldn't fully plead guilty or not guilty. This was because, for Aboriginal people, causing death wasn't always seen as a crime in the same way.

However, Judge Willis believed Bonjon was smart enough to say guilty or not guilty. So, he decided the case could continue to the main question: did the court have jurisdiction?

The Main Question: Court's Jurisdiction

The most important arguments in the case were about whether the court had the power to judge Bonjon. This was especially true since the crime was between two Aboriginal people.

Bonjon's Lawyer's Argument

Barry, Bonjon's lawyer, started by saying how important and new this case was. He mentioned a report by George Grey, the Governor of South Australia. Grey believed Aboriginal people should be tried under British law for crimes against each other. Barry used this to argue that the law was unclear. He said it was "so debatable a matter" that the government needed to clarify it.

Barry's main point was: "There is nothing in the establishment of British sovereignty in this country which authorizes our submitting the aboriginal natives to punishment for acts of aggression committed 'inter se.'" This means he argued that when Britain took control of Australia, it didn't automatically give them the right to punish Aboriginal people for crimes against each other.

Barry talked about how countries gain control over new lands. He referred to Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England. Blackstone described three ways:

- Occupancy: Finding empty, uncultivated land and settling it.

- Conquest: Taking land by force.

- Cession: Being given land through a treaty.

Barry argued that Britain claimed Australia by "occupancy alone." He said Australia wasn't empty, but was already lived in by Aboriginal people. He also said there was no treaty or agreement where Aboriginal people gave up their own laws.

He also used ideas from Vattel's The Law of Nations. Vattel wrote that if people are wandering in a country, that land belongs to them. Other people can settle there only if the original people don't need all the land. Barry said this didn't mean the original laws of the Indigenous people were automatically cancelled.

Barry also pointed out that the Native Police and the Port Phillip Protectorate were mainly for protecting white settlers. He argued that Aboriginal people had their own legal system. He was ready to bring witnesses to explain how Aboriginal law handled such matters. He said that just because Aboriginal laws were different from English laws, it didn't mean they weren't valid.

He gave examples of different legal systems existing together. He mentioned Spanish law in Minorca, Irish law in Ireland, French law in Canada, and Dutch law in the Cape Colony. He even reminded Judge Willis that he had dealt with Danish law in British Guiana.

Government Lawyer's Argument

Croke, the government's lawyer, argued that it was okay for civilized people to start a colony in an "uncivilized" country. This was fine as long as enough land was left for the original inhabitants. He said this was true in Australia.

Croke argued that the location of the crime, not the nationality of the people, decided which court had power. He said anyone in an English territory "owes a local allegiance to the Queen of England." This meant they were protected by the Queen and had to follow her laws. He asked if a Frenchman who killed another Frenchman in England wouldn't be judged by English law.

Finally, Croke said that a country's laws must apply to everyone in its territory. This was to make sure that serious crimes were punished. He said everyone in the territory deserved the protection of those laws.

Judge Willis's Decision

Judge Willis began by saying he wasn't forced to agree with other judges' past decisions. He noted that it was clear colonial courts had power over crimes between Aboriginal people and colonists. But he stressed that a judge must be careful not to use power when there's doubt.

Judge Willis often mentioned a report from the House of Commons on Aborigines. He quoted Bishop Broughton, who believed Aboriginal people were not unintelligent. Instead, their way of life was due to their "love of erratic liberty" (freedom to move around). He also quoted Saxe Bannister, who argued that Aboriginal customary laws should be studied and respected. From these, Judge Willis concluded that Aboriginal people had their own legal system. He felt treaties should have been made with them.

The Judge then talked about the decline in Aboriginal population near settlements. He wondered why, if Aboriginal people were British subjects, the government hadn't helped them. He also questioned why the courts hadn't protected them. He mentioned Batman's Treaty, which was an attempt to buy land from Aboriginal people for very little. He was glad this "bargain" was stopped. He regretted that no official treaties were made with Aboriginal peoples.

Judge Willis asked a key question: Did Britain's claim of power completely remove Aboriginal people's right to their land and their self-governing communities? Or did it just make them "dependent allies" who still kept their own laws?

He said the answer depended on how Britain gained control. He noted that while British law claimed Australia by "occupation," the country was not empty. It was already occupied. It wasn't taken by conquest or given by treaty. Instead, Judge Willis believed control was gained under Vattel's idea: a "civilized" people could take land from "uncivilized" people, as long as enough land was left for them.

Judge Willis gave the example of William Penn, who negotiated with the Lenape Native Americans. He said Penn's example had been "neglected." He felt the many violent clashes between Aboriginal people and white settlers showed that Aboriginal tribes were "neither a conquered people, nor have tacitly acquiesced in the supremacy of the settlers." This means they hadn't been defeated in war, nor had they quietly agreed to British rule.

He compared the situation to the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand, signed a year earlier. He couldn't see why Aboriginal people in Australia should be treated differently from the Māori in New Zealand. He believed that if the American experience was relevant for Māori, it should also apply to Aboriginal people in Australia.

Judge Willis also contrasted this with Jamaica, which Britain gained by conquest. There, a treaty allowed the Jamaican Maroons to govern themselves by their own laws for crimes among themselves. He also mentioned Saint Vincent, where the British made a peace treaty with the local Carib people.

He then compared Australia to areas under the British Raj in India. In India, laws were made for both British and native people. But Judge Willis said, "There is no express law, that I am aware of, that makes the Aborigines subject to our colonial code."

Finally, Judge Willis disagreed with the idea that Aboriginal people were like foreigners traveling in another country. He said that in Australia, "the colonists and not the aborigines are the foreigners." He called the colonists "exotics" (from elsewhere) and the Aboriginal people "indigenous" (native). He saw Aboriginal people as "the native sovereigns of the soil," and the colonists as "uninvited intruders."

Judge Willis concluded: "I am at present strongly led to infer that the Aborigines must be considered and dealt with... as distinct, though dependent tribes governed among themselves by their own rude laws and customs. If this be so, I strongly doubt the propriety of my assuming the exercise of jurisdiction in the case before me."

He said the question was too important to decide immediately. He wanted to see the lives of Aboriginal people improved and protected by laws that suited their needs.

What Happened After the Case?

After Judge Willis gave his opinion, the lawyers agreed to continue the trial. This was done without affecting the main question of jurisdiction. The court then took a break. The next morning, there was a discussion about how witness statements were taken. It seemed Bonjon hadn't been present for all of them. Also, the proceedings hadn't been fully translated for him. Because of this, the government's lawyer decided not to continue the case. Bonjon was held until the next month, and then he was set free.

A few months later, Bonjon's lawyer, Redmond Barry, became the Standing Counsel for the Aborigines. He was paid for each case. Soon after, Barry defended five Palawa people, including Truganini. They were accused of causing the death of two whalers. Barry used a similar argument to the Bonjon case. He argued that the five were not British subjects and the court had no power over them. He also said the jury should include Aboriginal people. However, Barry lost this case, and two of the five were executed.

Judge Willis's decision seemed to go against an earlier case from 1836, R v Murrell. In that case, the court decided it did have power over crimes between Aboriginal people. The Chief Justice at the time, James Dowling, criticized Judge Willis's decision. He said R v Murrell was the correct ruling. Governor Gipps and British officials agreed. If Bonjon hadn't been set free, the case would likely have gone to a higher court in Sydney. That court would probably have overturned Judge Willis's decision. Governor Gipps was so unhappy that he officially criticized Judge Willis. He also asked the government in Britain to pass a law to make sure colonial courts had power over crimes between Aboriginal people.

Some historians, like Ann Galbally, suggest Judge Willis's real goal was to embarrass the government. He had often disagreed with other judges and officials. However, Bruce Kercher argues that Willis's views came from the same ideas as the movement that ended slavery. Kercher believes Willis was a very important legal official who seriously considered that Aboriginal people had their own laws and customs.

Stanley Yeo compares Bonjon to the 1992 Mabo v Queensland case. Both cases accepted that Britain settled Australia and brought English law. But they also said that settlement alone wasn't enough to get rid of native laws. The Mabo case, however, also recognized that Britain could gain power over lands already lived in by native people. This was the way power was gained over Australia.

The R v Murrell case was published in 1986, but R v Bonjon was not. Because Murrell was decided by a higher court and was available to lawyers, it remained the accepted legal view for a long time. Kercher argues that R v Bonjon and another case, R v Ballard (1829), deserve more attention. He says they are more consistent with ideas about the rights of native peoples.

Images for kids