Rafael Díez de la Cortina y Olaeta facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

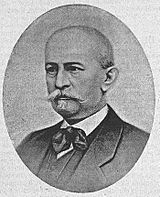

Rafael Díez de la Cortina y Olaeta

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Rafael Díez de la Cortina y Olaeta

1859 |

| Died | 1939 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | publisher, entrepreneur |

| Known for | linguist |

| Political party | Carlism |

| Signature | |

Rafael Díez de la Cortina y Olaeta, 1st Count of Olaeta (1859–1939) was a Spanish-American linguist. He is known as the first person to use sound recordings to teach foreign languages. He did this through his company, Cortina Academy of Languages, which he started in New York in the 1890s. In Spain, he is also remembered as a Carlist political activist and soldier. He joined the Carlist troops during the Third Carlist War and later represented the Carlist king in America.

Contents

Early Life and Family

The Díez de la Cortina family came from Cantabria, a region in northern Spain. In the mid-1700s, some family members moved to Marchena in Andalusia. They became important landowners there. Rafael's great-grandfather, José Antonio Díez de la Cortina Gutiérrez, built a family home in Marchena.

Rafael's grandfather, Juan Díez de la Cortina Layna Pernia (born 1782), became a leading landowner in the area. His family was part of a group of local noble families who became major property owners.

Rafael's father, José Díez de la Cortina Cerrato (died 1874), owned and rented large amounts of land. He married Elena Olaeta Bouyon, who came from a distinguished family of navy commanders. Rafael was the youngest of their three sons, born in 1859.

We don't know much about Rafael's early education. He married twice in the United States. First, in 1897, to Marguerete Canto Ingalis, and later in 1933, to Marion L. M. Fletcher. He did not have any children. Rafael lived in various places in New York, including Manhattan, before moving to Middletown, New York. He passed away suddenly in 1939 and was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

Rafael's older brother, José, became an important Carlist political leader in Andalusia in the early 1900s. The Carlist title of Count of Olaeta was given to Rafael in 1876.

Soldier in the Carlist War

The Carlist movement in Spain supported a different branch of the royal family for the throne. Rafael's family became involved with Carlism in the 1860s. His father, José Díez de la Cortina Cerrato, strongly supported the Carlist cause after the 1868 revolution in Spain.

In 1872, a Carlist uprising began in northern Spain. Rafael's father was eager to join the rebels. In June 1873, Rafael's 17-year-old brother, José, traveled north to learn about the war. When he returned in October 1873, their father formed a small group of about 20 men. This group included Rafael, his two brothers, a cousin, and other family associates and volunteers. Rafael was the youngest member.

The group traveled about 350 kilometers north to join a larger Carlist column. Starting in November 1873, Rafael began fighting in the war. His group fought in many battles across central Spain. In April 1874, during a battle at Piedrabuena, his father and oldest brother, Juan, were killed.

Rafael and his brother José survived the battle. José was wounded, and Rafael's horse was shot. They managed to escape to Portugal and then sailed to Bordeaux, France. From there, they crossed into the Carlist-controlled area in northern Spain. Rafael joined the artillery unit and was promoted to captain. In early 1876, during the final months of the war, the Carlist king gave Rafael the title of Count of Olaeta. He was later promoted to a higher rank. After the war ended, Rafael and his brother went into exile in France.

Carlist Representative in America

After the war, Rafael settled in Paris by 1878. In 1879, the Carlist king sent him to Mexico. By 1881, Rafael had moved from Mexico to New York, where he started teaching Spanish. From the 1880s onward, he served as the Carlist king's representative in North America. He remained close with the king, who even wrote a recommendation letter for Cortina's language textbook in 1889.

Rafael became an American citizen in 1889 but visited Spain often. In 1895, he met the Carlist king in Venice. It's not fully clear what his political work involved before the late 1890s.

Cortina was most active between 1896 and 1898, leading up to the Spanish–American War. He worked within the Spanish community in New York and wrote for a newspaper called Las Novedades. He tried to fight against the anti-Spanish news in American newspapers. He also started promoting the claims of the Carlist king. Thanks to his efforts, some US newspapers, like the New York Herald, published articles about Carlism.

In May 1898, during the Spanish-American War, many newspapers quoted Cortina. They discussed the Carlist claims, suggesting the Spanish government might fall. This helped to stir up American public opinion, though that wasn't Cortina's goal. He even claimed that the Carlist king would take the throne soon. He might have been involved in sending weapons to Carlist supporters. In 1901, a Spanish military official in Washington reported that Cortina helped identify a shipment of 5,000 rifles meant for the Carlists. It's unclear if he was working for both sides. Although he visited Spain often in the 1900s, he was not as involved in Carlist activities, focusing more on his language business.

Linguist and Businessman

In the early 1880s, Rafael Cortina began teaching Spanish. He claimed his Cortina Institute of Languages started in 1882. He also taught lessons at other places, like the Brooklyn Library and the Brooklyn YMCA. His big breakthrough was publishing The Cortina Method to Learn Spanish in Twenty Lessons in 1889.

Cortina believed that focusing on practical skills was better than just learning grammar rules. He claimed to have a master's degree from the University of Madrid. By 1891, he was promoting his "Cortina method," and in 1892, the Cortina School of Languages began advertising. His school had two locations in Brooklyn and Manhattan and taught nine languages in 20 lessons with native teachers.

Cortina was the first person to use a phonograph for teaching foreign languages. This was reported in The Phonogram journal in 1893. This became a major part of his business. He offered both in-person classes and self-study courses through mail. These courses included textbooks and sound recordings.

At first, he used phonograph cylinders. After 1896, these were made by Edison's National Phonographic Company. In 1908, he created his own brand of phonograph called Cortinaphone. From 1913, his company started making flat round records. The Cortina school taught in English until 1920, when they switched to teaching only in the target language. Around 1920, he promoted his "Cortina phonograph outfit," saying it was more effective than having a teacher.

Cortina's language business became very successful. His teaching method won awards. The school, renamed Cortina Academy of Languages in 1899, grew and moved to larger locations. Other schools started using his methods. His publishing house printed many editions of textbooks, and audio materials were even published with Columbia Records. His English correspondence courses were popular in South America and Mexico.

His business also grew in Spain, where he received official government support. Many experts at the time praised his teaching method. Even today, scholars say it was a big step forward in language teaching. The language school he founded was later called the Cortina Institute of Languages and operated until June 2015.

See also

In Spanish: Rafael Díez de la Cortina para niños

In Spanish: Rafael Díez de la Cortina para niños

- Carlism

- Traditionalism (Spain)

- Language education

- José Díez de la Cortina y Olaeta

- José Díez de la Cortina y Cerrato

- List of language self-study programs