Ramón Massó Tarruella facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ramón Massó Tarruella

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Ramón Massó Tarruella

1928 Pallejà, Spain

|

| Died | 14 November 2017 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | scholar, businessman |

| Known for | media expert, politician |

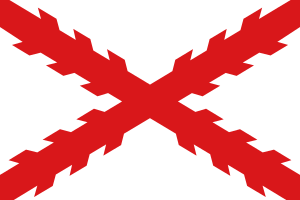

| Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista |

Ramón Massó Tarruella (1928 – 2017) was a Spanish expert in media and communications. He was also a former Carlist politician. Carlism was a political movement in Spain that supported a different branch of the royal family.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ramón Massó Tarruella was born into a wealthy and well-known family from Catalonia, a region in Spain. His grandfather, Ramón Massó Marcer, came from a small town by the sea. In 1885, he moved to Barcelona to start his own business. He created a company that made dyes for the textile industry, which makes clothes and fabrics.

Ramón's father, Juan Massó Soler, joined the family business in 1912. He helped it grow into a very successful chemical company. Ramón's parents had eight children, and they were all raised in a very Catholic and traditional home. Ramón's brothers, José Luis and Juan Antonio, later took over the family company. They turned it into a big chemical business that is still active today. Juan Antonio later became a priest and worked for Opus Dei in Australia.

When Ramón was a child, his family had to leave Barcelona. The city was controlled by anarchists during the early part of the Spanish Civil War. His family moved to San Sebastián, which was in the area controlled by the Nationalists. Ramón and his brothers joined a Carlist youth group called Pelayos. However, they left when this group was forced to join with another group called Falange. As a child, Ramón even protested against this change, shouting against General Franco and the Falange party.

After the war, his family returned to Barcelona. Ramón and his brothers became teenage members of Opus Dei there. In the late 1940s, Ramón moved to Madrid to study philosophy. During his university years, he joined a Carlist student group. He was upset that Carlism was losing its power in Francoist Spain, the country ruled by General Franco. Ramón became strongly against Franco's government. He took part in protests and fights against the official student organization. In 1954, he became a national leader of the Carlist student group.

Ramón Massó and the Carlist Movement

Ramón Massó was not happy with the older Carlist leaders. He felt they were stuck in the past. He and his group of young Carlists wanted to make big changes. They tried to convince the Carlist Prince, Don Javier, to take stronger action. When that didn't work, they decided to focus on Don Javier's oldest son, Carlos Hugo.

Carlos Hugo, who was studying in England, joined forces with Massó and his team. After spending some time learning Spanish politics, Carlos Hugo made his first public appearance at a big Carlist gathering called Montejurra in May 1957. Massó and his team carefully planned this event. Carlos Hugo's speech was a huge success. The crowd was excited by his youth and strong message. Massó and his team made sure that Carlos Hugo's message, called La Proclama de Montejurra, was shared with Carlists all over Spain.

In the following years, more and more people came to Montejurra. It became one of the largest public gatherings in Francoist Spain.

Carlos Hugo and his supporters, known as hugocarlistas, brought new ideas to the Carlist movement. They wanted to work with Franco's government in some ways to gain more freedom to act. However, Massó's real goal was to change the government from the inside. While other Carlist leaders focused on the army, Massó and his group reached out to workers and others who wanted a new social order.

This approach seemed to work. In the early 1960s, the Carlists were allowed to have more media and organizations. The hugocarlistas used this chance to start new newspapers like Azada y asta and Montejurra. They also created cultural clubs and their own workers' organization, which helped spread their political ideas.

As Carlos Hugo moved to Madrid, he organized his young helpers, including Massó, into his "Political Secretariat." Massó became the head of this group. The young Carlists started to have more power. Massó managed to push out a main opponent, José Luis Zamanillo, in 1964. After this, the hugocarlistas openly shared their vision for Carlism. They published a document called Esquema doctrinal, which talked about a monarchy with corporate (group-based) political organization, and ideas against big business and for democracy. By 1965, they were even talking about socialism and Marxism at their Montejurra gatherings.

Massó wanted to make Carlos Hugo the king and bring about big changes in Spain. He also wanted to stop another royal family branch, the Alfonsists, from taking the throne. The young Carlists tried to make Juan Carlos (who later became king) look bad in public. At the same time, Massó started a campaign to make Carlos Hugo popular across the country. He used modern media tricks, like creating exciting stories for newspapers (Carlos Hugo as a miner, doing parachute training, or at the Sanfermines festival). He also used the charm of Carlos Hugo's three sisters. This helped the Borbon-Parmas (Carlos Hugo's family) become well-known and liked in the media, even with strict censorship.

A big event happened in 1964 when Carlos Hugo married Princess Irene of the Netherlands. However, Franco's government then decided to stop promoting Carlos Hugo. Franco was worried that Carlos Hugo was becoming too popular. Even though the wedding was shown widely in other European countries, Spanish media played it down. This showed Massó the limits of his strategy, and he became very disappointed.

By the mid-1960s, Massó realized his plan wasn't working. He also saw that using strong Leftist words like "socialism" was dividing the Carlist movement. In 1965, he moved from Madrid to Pamplona and started teaching at an Opus Dei university. As more people opposed his influence, Massó stepped down as head of the Political Secretariat in 1966. In 1967, he and some of his friends left politics completely.

Media Expert and Teacher

In the late 1960s, Massó settled in Pamplona. He became a teacher at IESE Business School, a well-known business school started by Opus Dei. He also completed a leadership program there for top business managers. Later, Massó became unhappy with Opus Dei and its role in helping Juan Carlos become king. He left the organization and moved to Barcelona. There, he joined the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB), where he became a professor of advertising.

In 1977, Massó wrote a small book called Estrategia para unas extrañas elecciones. This book made him known in the local media and led to him working with La Vanguardia, a major newspaper. He became a main commentator on politics and public affairs for the newspaper until 1984. During Spain's transition to democracy, Massó observed the changes as a scholar. He tried to be an unbiased observer, but his dislike for Franco's rule and his support for reforms were clear. He often referred to Lenin as a political authority. His writings suggested he accepted Juan Carlos as king and his role in Spain's transition. In the late 1970s, he also worked on a popular history series about Catalonia.

Communication Expert

In the mid-1970s, Massó helped start Alas, one of Spain's first media agencies. He became the head of its Barcelona office. Around the same time, he created the term "politing." This word combined "politics" and "marketing." It described a special field of knowledge that mixed social sciences, public relations, and politics. His book Introducción al “politing”. Lanzamiento de un aspirante (1976) won awards and gained a lot of interest. The book explained the basics of political marketing. It also included many hints about his own experiences helping Carlos Hugo in politics from 1957 to 1967.

The success of launching Carlos Hugo helped Massó become known as an expert in public relations. He also became a successful businessman. He claimed to have created the brand for La Caixa, a big Spanish bank. He also worked on social campaigns, like those for cancer awareness. He wrote another book, De la magia a la artesanía: el politing del cambio español (1980). This made him a nationally recognized scholar, and he gave courses at various institutions.

In the 1990s, Massó focused on media with books like El exito de la cultura light: Anuncios y noticias (1993) and Noticias frente a hechos: Entender la realidad despues de leer los periodicos (1997). Later, he became interested in a wider area called "integral communication." This involved combining different ways of sharing information. He helped start the Institut de Comunicació Integral in Barcelona. This was an independent college that taught marketing, brand communications, and public relations. He became its president. This institute became a popular place for education.

In his last ten years, Massó published more books about culture, communications, and politics. These included Otro rey para España: crónica del lanzamiento y fracaso de Carlos Hugo (2004), which was about Carlos Hugo's political journey. He even wrote a children's book called La segunda vida de Don Jos Kintana (1999). He also used Twitter and Facebook, though he was not very active in his final years.

See also

In Spanish: Ramón Massó Tarruella para niños

In Spanish: Ramón Massó Tarruella para niños

- Carlism

- Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma

- Francoism

- Communication

- Mass media

- Models of communication

- Popular culture studies

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |