Richard Hamming facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Hamming

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | February 11, 1915 Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Died | January 7, 1998 (aged 82) Monterey, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | University of Chicago (B.S. 1937) University of Nebraska (M.A. 1939) University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign (Ph.D. 1942) |

| Known for |

|

| Awards | Turing Award (1968) IEEE Emanuel R. Piore Award (1979) Harold Pender Award (1981) IEEE Hamming Medal (1988) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Some Problems in the Boundary Value Theory of Linear Differential Equations (1942) |

| Doctoral advisor | Waldemar Trjitzinsky |

| Influenced | David J. Farber |

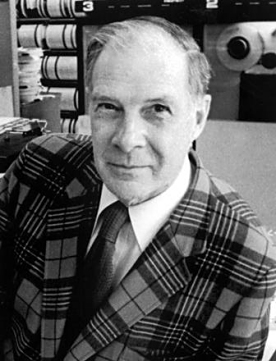

Richard Wesley Hamming (February 11, 1915 – January 7, 1998) was an American mathematician. His work greatly helped the fields of computer engineering and telecommunications. He invented important ideas like the Hamming code, the Hamming window, Hamming numbers, and the Hamming distance.

Hamming was born in Chicago. He studied at the University of Chicago, University of Nebraska, and the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. He earned his PhD in mathematics. In 1945, he joined the Manhattan Project. There, he programmed early IBM calculating machines.

After the war, he worked at Bell Telephone Laboratories from 1946 to 1976. He was involved in many major achievements there. For his important work, he received the Turing Award in 1968. After retiring from Bell Labs, he taught at the Naval Postgraduate School. He focused on teaching and writing books until his death in 1998.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Richard Wesley Hamming was born in Chicago, Illinois, on February 11, 1915. His father was a credit manager and his mother was Mabel G. Redfield. Richard grew up in Chicago and went to Crane Technical High School.

He first wanted to study engineering. But money was tight during the Great Depression. The only scholarship he got was from the University of Chicago, which had no engineering school. So, he chose to study science, focusing on mathematics. He earned his Bachelor of Science degree in 1937. He later felt this was a good change. He said that as an engineer, he might have missed out on exciting new research.

College and PhD Studies

Hamming earned his Master of Arts degree from the University of Nebraska in 1939. Then, he went to the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. There, he wrote his PhD paper on "Some Problems in the Boundary Value Theory of Linear Differential Equations." His advisor was Waldemar Trjitzinsky.

While studying, he read The Laws of Thought by George Boole. The University of Illinois awarded him his Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1942. He then became a math instructor there. On September 5, 1942, he married Wanda Little, a fellow student. They stayed married until his death and had no children. In 1944, he became a professor at the J.B. Speed Scientific School in Louisville, Kentucky.

Working on the Manhattan Project

During World War II, Hamming joined the Manhattan Project in April 1945. He worked at the Los Alamos Laboratory. His job was to program IBM calculating machines. These machines solved complex math problems for the project's physicists. His wife, Wanda, also worked at Los Alamos as a "human computer."

Hamming stayed at Los Alamos until 1946. He then took a job at Bell Telephone Laboratories. He even bought Klaus Fuchs's old car for the trip! Hamming later said his role at Los Alamos was like a "computer janitor." But he saw how computers could simulate experiments that were impossible to do in a lab. He realized that computers would change science forever.

Innovations at Bell Laboratories

At Bell Labs, Richard Hamming shared an office with Claude Shannon for a while. They were part of a group called the "Young Turks." Hamming described them as "first-class troublemakers." They did things in new ways and still got great results. This meant management often left them alone.

Hamming was hired to work on elasticity theory. But he spent a lot of time with the calculating machines. In 1947, he set the machines to run a long calculation over a weekend. On Monday, he found an error had stopped the process early. Digital machines use bits, which are sequences of zeroes and ones. If even one bit was wrong, the whole calculation could be ruined.

Solving the Error Problem

Hamming thought: "If the computer can tell when an error happened, it should be able to tell where the error is." He decided to solve this problem. He knew it would be useful in many areas. If you know which bit is wrong, you can fix it.

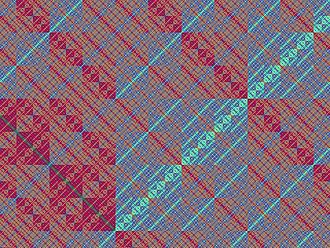

In 1950, he published a very important paper. He introduced the idea of the Hamming distance. This is the number of positions where two code words are different. It shows how many changes are needed to turn one code word into another. This led to a family of error-correcting codes called Hamming codes. This work not only solved a big problem in computers and communication, but it also started a whole new field of study.

The Hamming bound is another idea related to error correction. It sets a limit on how efficient any error-correcting code can be. Codes that reach this limit are called perfect codes, and Hamming codes are perfect codes.

Other Contributions

Hamming also worked on solving differential equations using computers. He improved a method called Milne's Method, creating the Hamming predictor-corrector. He also did a lot of research on digital filters. He invented a new filter called the Hamming window. He even wrote a book about it called Digital Filters (1977).

In the 1950s, he programmed one of the first computers, the IBM 650. With Ruth A. Weiss, he developed the L2 programming language in 1956. This was one of the earliest computer languages. It was used a lot at Bell Labs and by other users.

The term "Hamming numbers" is used in computer science for regular numbers. These are numbers whose only prime factors are 2, 3, and 5. Even though he didn't discover them, the problem of finding them efficiently became known as "Hamming's problem."

Hamming avoided management roles at Bell Labs. He was offered promotions many times but always found a way to make them temporary. He felt that avoiding management was one of his biggest failures.

Later Life and Teaching

Richard Hamming was president of the Association for Computing Machinery from 1958 to 1960. In 1960, he predicted that half of Bell Labs' budget would one day be spent on computing. His colleagues thought this was too high, but his prediction actually turned out to be too low!

Hamming became very interested in teaching later in his life. From 1960 to 1976, he taught at several universities. These included Stanford University, Stevens Institute of Technology, and Princeton University. He noticed that he had worked on many important projects in the first half of his career at Bell Labs, but fewer in the second half. So, he decided to retire in 1976 after 30 years.

In 1976, he moved to the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. There, he worked as a professor in computer science. He stopped doing research and focused on teaching and writing books. He became a Professor Emeritus in June 1997. He gave his last lecture in December 1997. He passed away from a heart attack on January 7, 1998. His wife, Wanda, survived him.

Awards and Recognition

Richard Hamming received many important awards for his work:

- Turing Award, Association for Computing Machinery, 1968.

- IEEE Emanuel R. Piore Award, 1979. This was for his work on error-correcting codes and early computer languages.

- Member of the National Academy of Engineering, 1980.

- Harold Pender Award, University of Pennsylvania, 1981.

- IEEE Richard W. Hamming Medal, 1988.

- Fellow of the Association for Computing Machinery, 1994.

- Basic Research Award, Eduard Rhein Foundation, 1996.

The IEEE Richard W. Hamming Medal is named after him. It is given each year by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). It honors "exceptional contributions to information sciences, systems and technology." Richard Hamming was the first person to receive this medal. The back of the medal shows a Hamming parity check matrix, which is part of his error-correcting code.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Richard Hamming para niños

In Spanish: Richard Hamming para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |