Mechanical calculator facts for kids

A mechanical calculator is a machine that uses gears and levers to do math problems like adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing. They were like early computers, but they used moving parts instead of electricity. Most were big, like a small desk, and are not used much today because of electronic calculators and digital computers.

The idea of a mechanical calculator goes way back! In 1623, a smart person named Wilhelm Schickard designed one. His machine used Napier's bones for multiplying and dividing, and a special dial for adding and subtracting. Sadly, his machine probably didn't work perfectly and might have broken if you added big numbers. Schickard stopped working on it in 1624.

About 20 years later, in 1642, Blaise Pascal invented his own mechanical calculator, called Pascal's Calculator or Pascaline. He made it to help his dad, who was a tax collector and had to do lots of math. Pascal's machine was much better at handling carries (like when you add 1 to 9 and get 10).

In 1672, Gottfried Leibniz started making a new machine called the Stepped Reckoner. It used a special part called the Leibniz wheel. This machine was very important because it was the first to let you move parts around to help with calculations. The Leibniz wheel was used in many calculators for 200 years!

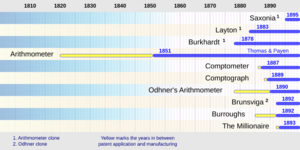

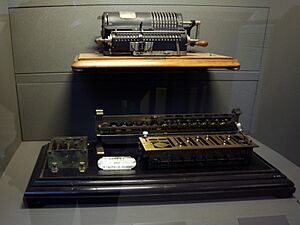

The first calculator that was sold widely and used every day in offices was Thomas' arithmometer, made in 1851. It was strong and reliable. For 40 years, it was the only mechanical calculator you could buy. Later, the Odhner Arithmometer became very popular.

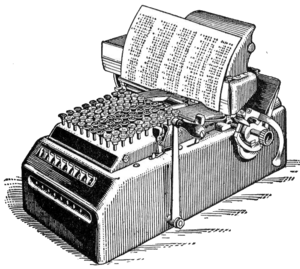

New features kept coming! In 1887, the comptometer was the first to have a keyboard with keys for each number. In 1902, the Dalton adding machine was the first to have a simple 10-key keyboard. By the 1970s, mechanical calculators were replaced by electronic ones.

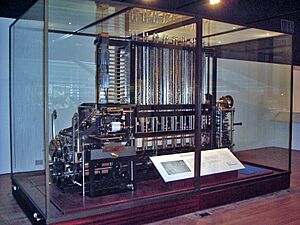

Charles Babbage designed two amazing mechanical calculators that were too advanced for his time. His difference engine could automatically calculate and print math tables. Later, his analytical engine was even more special. It was the first programmable calculator, meaning you could give it instructions using punched cards. This machine was a blueprint for modern computers!

Contents

Early Calculating Ideas

People have always wanted to do math faster and with fewer mistakes. Long ago, they used pebbles, then the abacus. The abacus uses beads on wires to help count. It was probably invented by ancient people and then spread to Europe and Asia.

After the abacus, there wasn't much progress until John Napier invented his "numbering rods" or Napier's Bones in 1617. These helped with multiplication. But the first real mechanical calculating machine, as we think of it today, was Pascal's calculator in 1642.

Before mechanical calculators, there were also early analog computers. These machines used gears and moving parts to show things like time or positions of stars. Examples include odometers (which measure distance) and the amazing Antikythera mechanism, an ancient Greek device that was like a geared astronomical clock. These machines were different from calculators because they didn't let you freely add or subtract numbers like a calculator does.

The 17th Century: First Machines

New Inventions

The 1600s were the start of mechanical calculators. Blaise Pascal invented his calculator in 1642. He showed that machines could do calculations that people thought only humans could do.

It was hard to build these machines perfectly back then. The tools and skills weren't as good as they are now. This problem wasn't fully solved until the 1800s.

The 1600s also saw other helpful math tools like Napier's bones, logarithm tables, and the slide rule. These tools were easy for scientists to use for multiplying and dividing, which slowed down the development of mechanical calculators until the arithmometer came out in the mid-1800s.

Schickard's and Pascal's Ideas

In 1623, Wilhelm Schickard wrote letters to Johannes Kepler about his "arithmetical instrument," also called a "calculating clock." It was designed to help with all four basic math operations. Schickard hoped it would help calculate star tables. His machine could add and subtract six-digit numbers and would ring a bell if the number got too big. It also had Napier's bones to help with multiplying. Schickard asked a clockmaker to build it, but it was destroyed in a fire. He gave up on the project soon after.

Schickard's machine used strong clock wheels. But when you needed to "carry over" a number (like when 9 + 1 makes 10), it could be hard for the gears to move smoothly.

Blaise Pascal invented his mechanical calculator in 1642. He worked for three years and made 50 test models before showing it to the public. He built 20 of these machines over the next 10 years. His machine could add and subtract directly. It was very well-made, and people at the time didn't complain about its carry mechanism, even though it was used a lot.

Pascal was only 19 when he invented his machine. He saw how much math his father had to do as a tax supervisor and wanted to make it easier. He had a great mix of science and mechanical skill.

In 1672, Gottfried Leibniz started working on a calculator that could multiply directly. He designed a new machine called the Stepped Reckoner. It used his special Leibniz wheels. This was the first calculator that had a movable part and could "remember" the first number you put in. Leibniz built two of these machines, one in 1694 and one in 1706. Only the 1694 machine still exists today.

Leibniz invented his special wheel and the idea of a two-motion calculator. But even after 40 years, he couldn't make a machine that worked perfectly. This means Pascal's calculator was the only fully working mechanical calculator in the 1600s. Leibniz also thought of the idea of a pinwheel calculator. He believed that smart people shouldn't waste time on simple calculations that machines could do.

Other Early Machines

Many inventors in the 1600s were inspired by how clocks worked. But just linking gears together wasn't enough for a good calculator. Schickard used a special gear to help with carries. Pascal improved this with his clever "sautoir" mechanism. Leibniz went even further with his movable part for multiplication.

Many early "calculating clocks" from the 1600s didn't have a good way to carry numbers across the whole machine. This meant their gears would jam if you needed to carry a number over many places. A more successful calculating clock was built by Giovanni Poleni in the 1700s.

- In 1623, Wilhelm Schickard designed a calculating clock. The first one being built was destroyed, and he stopped the project. When replicas were made in the 1960s, they found that his design needed more parts to work well.

- Around 1643, a French clockmaker claimed to have built a calculating clock like Pascal's. Pascal stopped his work until he was sure his invention would be protected. It turned out the clockmaker's machine didn't work right.

- In 1659, Tito Livio Burattini built a machine with nine separate wheels. But you had to manually add the carries at the end of the calculation.

- In 1666, Samuel Morland invented a machine for adding money. It also had a small carry wheel above each digit, so the carry wasn't added directly. He also made a multiplying machine using Napier's bones.

- In 1673, René Grillet described a calculating machine that he said was smaller than Pascal's. But his machines didn't have a carry mechanism, so they weren't true mechanical calculators.

The 18th Century: New Designs

Early Prototypes

The 1700s saw the first mechanical calculator that could multiply automatically. It was designed and built by Giovanni Poleni in 1709 and was made of wood. For all machines in this century, division still required the user to do some work, so they only helped with dividing, like an abacus.

- In 1709, Italian Giovanni Poleni built the first calculator that could multiply automatically. It used a pinwheel design and was made of wood.

- In 1725, the French Academy of Sciences approved a calculator by Lépine, based on Pascal's design. It had problems with carries if too many happened at once.

- In 1727, German Anton Braun showed the first machine that could do all four operations (add, subtract, multiply, divide) to Emperor Charles VI. It was cylindrical and made of metal, looking like a fancy clock.

- In 1730, the French Academy of Sciences approved three machines by Hillerin de Boistissandeau. Some of his machines used springs to help with carries, similar to Pascal's design but using spring energy instead of gravity.

- In 1770, Philipp Matthäus Hahn, a German pastor, built two circular calculators based on Leibniz's cylinders.

- In 1775, Lord Stanhope from the UK designed a pinwheel machine. He also designed a machine using Leibniz wheels in 1777. He even made a "Logic Demonstrator" to solve logic problems.

- In 1784, German Johann-Helfrich Müller built a machine similar to Hahn's.

The 19th Century: Calculators for Everyone

The Industry Begins

Luigi Torchi invented the first machine that could multiply directly in 1834.

The mechanical calculator industry really started in 1851 when Thomas de Colmar released his simpler Arithmomètre. This was the first machine strong and reliable enough for daily office use.

For 40 years, the arithmometer was the only mechanical calculator you could buy, and it was sold worldwide. By 1890, about 2,500 arithmometers had been sold.

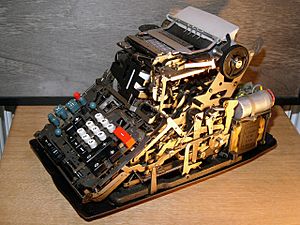

The 1800s also saw Charles Babbage's amazing calculator designs. His difference engine, started in 1822, was the first automatic calculator. His analytical engine, started in 1834, was the first programmable calculator, using punched cards for instructions. This machine was a blueprint for the mainframe computers of the mid-1900s.

Desktop Calculators Become Popular

- In 1851, Thomas de Colmar made his arithmometer simpler. It became a basic adding machine, but with a moving part, it could still do multiplication and division easily. Thomas could now build strong and reliable machines. This launched the mechanical calculator industry. Banks, insurance companies, and government offices started using arithmometers every day.

- In 1878, Burkhardt in Germany was the first to make a copy of Thomas's arithmometer. Thomas had been the only maker until then, selling about 1,500 machines. Eventually, 20 European companies would make copies of the arithmometer.

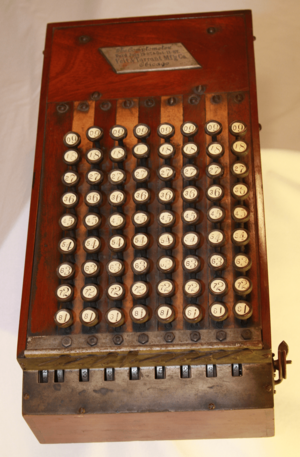

- Dorr E. Felt in the U.S. patented the Comptometer in 1886. This was the first successful calculator where you just pressed the keys to get the answer, without needing to pull a lever. In 1961, a comptometer-type machine was the first to get an all-electronic engine.

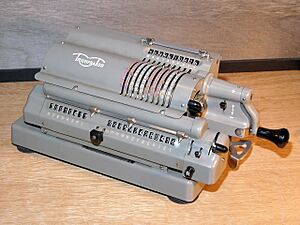

- In 1890, W. T. Odhner started making his own calculator. He sold 500 machines that year. His company made 23,000 machines before closing in 1918. The Odhner Arithmometer was a new version of Thomas's arithmometer, using a pinwheel engine. This made it cheaper and smaller, but it still worked in a similar way.

- In 1892, Odhner sold part of his factory to Grimme, Natalis & Co. They moved the factory and sold their machines under the name Brunsviga. Many companies copied Odhner's machine, and millions were sold until the 1970s.

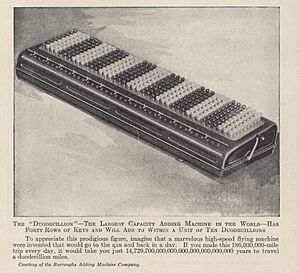

- In 1892, William S. Burroughs started making his printing adding calculator. His company, Burroughs Corporation, became a leader in accounting machines and computers.

- The "Millionaire" calculator came out in 1893. It could multiply directly by any digit with just "one turn of the crank for each figure."

Automatic Calculators

- In 1822, Charles Babbage showed a small model of his difference engine. This was a mechanical calculator that could hold and work with seven numbers of 31 digits each. It was the first time a calculating machine could work automatically, using the results of its last calculation for the next one. It was also the first calculating machine to use a printer. Babbage stopped working on this machine around 1834.

- In 1847, Babbage started designing an improved difference engine, "Difference Engine No. 2." Babbage never fully built these designs. In 1991, the London Science Museum built a working Difference Engine No. 2 using 19th-century technology, following Babbage's plans.

- In 1855, Per Georg Scheutz finished a working difference engine based on Babbage's design. It was the size of a piano and was used to create tables of logarithms.

- In 1875, Martin Wiberg redesigned the Babbage/Scheutz difference engine and built a smaller version, the size of a sewing machine.

Programmable Calculators

- In 1834, Babbage started designing his analytical engine. This machine is seen as the ancestor of modern mainframe computers. It had separate ways to put in data and programs (like a primitive Harvard architecture), printers for results, a processing unit (called the "mill"), memory (called the "store"), and the first set of programming instructions.

- In 1843, Ada Lovelace wrote an algorithm (a set of instructions) to calculate Bernoulli numbers for the analytical engine. This is considered the first computer program.

- From 1872 to 1910, Henry Babbage, Charles Babbage's son, worked on building the "mill" (the central processing unit) of his father's machine. In 1906, he successfully showed it working, printing the first 44 multiples of pi.

Cash Registers

The cash register, invented by American saloon owner James Ritty in 1879, helped businesses organize money and prevent dishonesty. It was an adding machine with a printer, a bell, and a display that showed the amount of money for a transaction.

Cash registers were easy to use and quickly adopted by many businesses. By 1900, NCR Corporation alone had built 200,000 cash registers, far more than the number of mechanical calculators sold.

1900s to 1970s: The Golden Age and Decline

Mechanical Calculators at Their Best

In the first half of the 1900s, mechanical calculators kept getting better. Some were operated by hand cranks, while others used electric motors.

The Dalton adding machine, introduced in 1902, was the first of its kind to use only ten keys, making it easier to use.

In 1948, the tiny cylindrical Curta calculator was introduced. It was small enough to hold in one hand and was a very advanced version of the stepped-gear mechanism.

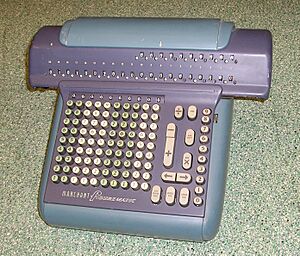

From the early 1900s through the 1960s, mechanical calculators were everywhere in offices. Big companies like Friden, Monroe, and SCM/Marchant made them. These machines were motor-driven and had movable parts to show results. Most had "full" keyboards, meaning each number had its own column of nine keys, allowing you to enter several digits at once.

These machines could add and subtract quickly. Multiplication and division were done by repeating additions and subtractions. Some advanced machines could even find square roots. Handheld mechanical calculators like the 1948 Curta were used until electronic calculators took over in the 1970s.

Many European calculators used the Odhner mechanism. These included the Original Odhner, Brunsviga, and others like Triumphator, Thales, Walther, Facit, and Toshiba. Most were hand-cranked, but some had motors.

While the Dalton machine introduced a 10-key printing adding machine in 1902, it took many decades for these features to appear in full "computing" machines that did all four operations. The Facit-T (1932) was the first popular 10-key computing machine. The Olivetti Divisumma-14 (1948) was the first computing machine with both a printer and a 10-key keyboard.

Full-keyboard machines were also built until the 1960s by companies like Mercedes-Euklid, Archimedes, MADAS, Friden, Marchant, and Monroe.

The Marchant calculators were very fast, able to do 1,300 additions per minute. They had complex internal gears to achieve this speed.

Some machines were made for specific tasks, like the Binary-Octal Marchant, which was a base-8 (octal) machine. It was used to check early electronic computers for accuracy because the mechanical calculators were more reliable back then!

There were also special versions for different money systems, like pounds, shillings, and pence, with extra columns for those units.

The End of an Era

Mechanical calculators continued to be sold, but in smaller and smaller numbers, into the early 1970s. Many companies closed or were bought out. Comptometer-type calculators were often kept for adding and listing, especially in accounting. A skilled operator could enter numbers faster on a comptometer than on a 10-key electronic calculator. However, the rise of computers and simple electronic calculators eventually ended the era of mechanical calculators. By the end of the 1970s, even the slide rule was no longer used.

See also

- Abacus

- Adding machine

- Calculator

- History of computing hardware

- Mechanical computer

- Tabulating machine

- George Brown (inventor)

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |