Richard Wetherill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Wetherill

|

|

|---|---|

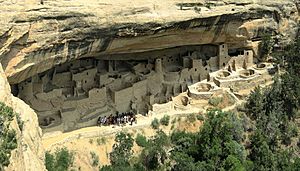

Cliff Palace, first excavated by Wetherill.

|

|

| Born | June 12, 1858 |

| Died | June 10, 1910 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | American |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Archaeology |

Richard Wetherill (1858–1910) was an American rancher and amateur archaeologist. He became famous for discovering and exploring ancient sites in the Southwestern United States. These sites belonged to the Ancient Pueblo people.

Wetherill is known for rediscovering Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde, Colorado. He also helped name these ancient people "Anasazi," which is a Navajo word meaning "ancient enemies." His work included digging at Kiet Seel in Navajo National Monument and Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon.

Besides his archaeological work, Wetherill was a rancher, guide, and trading post owner. Some professional archaeologists criticized him, calling him a "pot hunter." However, he often sold or gave his finds to important museums. His work helped make Mesa Verde a National Park and Chaco Canyon a National Monument. Wetherill died in 1910 in Chaco Canyon under mysterious circumstances.

Contents

Early Life and Family History

Richard Wetherill was born on June 12, 1858, in Chester, Pennsylvania. He was the oldest of seven children. His parents were Benjamin Kite Wetherhill and Marion Tompkins, who were Quakers.

When Richard was one year old, his family moved to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. They later moved to Joplin, Missouri in 1876, and then to Rico, Colorado three years later. In 1880, the family settled in the Mancos River valley in Colorado.

In 1882, the Wetherill family started the Alamo Ranch. This ranch was about 3 miles (5 km) south of Mancos. They built their ranch on land they claimed under the Homestead Act. By 1895, they owned 1,000 acres (400 ha) of land, but they had many debts.

Richard Wetherill married Marietta Palmer on December 12, 1896, in Sacramento. They had five children: Richard, Elizabeth, Robert, Marion, and Ruth.

Discovering Mesa Verde's Ancient Cliff Dwellings

The Wetherill family grazed their cattle along the Mancos River. They knew about the ancient ruins in the canyon. Richard and his brothers loved to search for ruins and artifacts. A Ute Indian named Acowitz told Richard about a very large ruin in Cliff Canyon.

On December 18, 1888, Richard Wetherill and his brother-in-law, Charlie Mason, saw Cliff Palace for the first time. They saw it from the top of the mesa. Wetherill named it Cliff Palace. It is the largest cliff dwelling in the United States. It had been untouched for almost 700 years since the Ancestral Puebloans left it.

Richard Wetherill, along with his father and brothers, explored Cliff Palace. They dug, excavated, and collected many artifacts. They also took notes and photographs. The Wetherills sold some of their finds to the Historical Society of Colorado. They also offered a collection to the Smithsonian Institution, but there was no money to buy them.

News of Wetherill's discovery spread quickly. Many people came to stay with the Wetherills to explore the cliff dwellings. One visitor was mountaineer and photographer Frederick H. Chapin. He visited in 1889 and 1890. He wrote about the landscape and ruins in a book called The Land of the Cliff-Dwellers.

In 1891, the Wetherills hosted Gustaf Nordenskiöld, a Swede. Nordenskiöld continued the excavations at Cliff Palace. In 1893, he published a scientific book about his work called The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde. Nordenskiöld sent his artifacts to Sweden. This caused anger and lawsuits in the United States. This anger eventually led to the U.S. Antiquities Act. This law made it illegal to export ancient artifacts without a license. It also led to Mesa Verde becoming a National Park in 1906.

Nordenskiöld taught Wetherill some basic archaeological methods. He taught him to dig carefully with a trowel and to take many notes. Nordenskiöld called Wetherill a cowboy "with a surprising degree of education." Even so, many professional archaeologists called Wetherill a "pot hunter" or "vandal." However, many large museums in the United States hired him, paid for his trips, and bought his discoveries.

Wetherill named the cliff dwellers the Anasazi. This is a Navajo term for "ancient enemy." He also created the term "basket people" for an older group he found. These people are now known as Basket Makers. For many years, archaeologists did not believe Wetherill's idea that the Basket Makers lived before the cliff dwellers. But his idea was later proven to be correct.

Exploring Tsegi Canyon's Ancient Sites

In 1892, Wetherill met Frederick E. Hyde, a doctor from New York who loved archaeology. Hyde, his sons, and Wetherill started the Hyde Exploring Expedition. They agreed that all artifacts and notes would go to the American Museum of Natural History.

Wetherill led a team that dug in Grand Gulch, Utah, in 1893 and 1894. In 1895, Richard Wetherill, his brother Al, and Charlie Mason traveled to Arizona. They excavated the Keet Seel (Broken Pottery) ruin in Tsegi Canyon. This ruin is now part of the Navajo National Monument.

Keet Seel is a spectacular site with buildings up to three stories high. It is a little smaller than Cliff Palace. Wetherill described his findings there as "the finest collection of pottery I have seen."

Archaeological Work in Chaco Canyon

In 1896, Wetherill and the Hyde Exploring Expedition (HEE) began large-scale excavations in Chaco Canyon. This area was on the Navajo Reservation. The American Museum of Natural History oversaw the work.

George Pepper, a 23-year-old museum employee, was put in charge. Wetherill was given a secondary role, supervising the Navajo workers. Pepper did not like the hard work of digging up artifacts. This caused tension between him and Wetherill.

Wetherill excavated the Pueblo Bonito great house. After the first season, he sent a train car full of artifacts to the American Museum. More excavations in Chaco Canyon in 1897, 1898, and 1899 produced even more artifacts.

However, the Wetherill family was losing money. Their Alamo ranch in Colorado was deeply in debt. It was eventually sold in 1902. Richard Wetherill needed a way to earn money. He opened a trading post at Chaco Canyon. He used rooms at Pueblo Bonito to store goods. Wetherill also used wooden beams from the ruins to build a three-room house. This house served as his trading post and living space for Pepper, Wetherill, his wife Marietta, their baby son, and a nanny.

Marietta did most of the trading. The Navajo people called her "Asdzani" ("Little Woman"). The Navajo called Wetherill "Anasazi," and he adopted this name for the ancient culture he was studying. The Wetherill family's business grew. By 1901, they ran eight trading posts, a wholesale store, and a retail store. They also bought and sold Navajo rugs.

Wetherill's work in Chaco Canyon angered some professional archaeologists. In 1901, Edgar Lee Hewett accused the Hydes and Wetherill of being "professional pot hunters" who were "vandalizing the ruins." The Governor of New Mexico and the Santa Fe Archaeological Society also criticized them.

Federal investigations in 1901 and 1902 cleared the Hydes and Wetherill of the charges. However, Wetherill was removed from his position with the Hyde Exploring Expedition. In response to his critics, Wetherill claimed ownership of 160 acres of land in Chaco Canyon under the Homestead Act. This land included many of the ruins. His claim was first denied but approved in 1907, though it did not include the main ruins.

Wetherill also owned many livestock animals. This caused problems with the Navajo people because his animals competed for grazing land. He was also criticized by the superintendent of the Navajo Reservation.

In 1905, Richard, his brother Win, and his wife Marietta created an exhibition at the St. Louis World's Fair. They brought 16 Navajo people with them. In 1907, Richard gave up his claim on the ruins in Chaco Canyon. This was done on the condition that it would become a National Park. President Theodore Roosevelt declared Chaco Canyon National Monument on March 11, 1907.

Richard Wetherill's Death

In 1910, Wetherill was still living in Chaco Canyon. He was homesteading and running his trading post at Pueblo Bonito. On June 10, he was shot and killed by a young Navajo man named Chiishchilí Biyeʼ.

The reasons for Wetherill's death are debated. Some say he was murdered by the Navajo man. Others suggest that a local Indian Agent influenced the murderer. This agent wanted to build a dam and an Indian School in the canyon. Biye', who was charged with the murder, spent several years in prison. He was released in 1914 due to poor health.

Although often described as wealthy, Wetherill's only asset when he died was ranch property worth five thousand dollars. People owed him more than eleven thousand dollars, but his widow collected very little of it. Marietta Wetherill lived a modest life and died in Albuquerque in 1954.

Richard Wetherill and his wife Marietta are buried in a small cemetery west of Pueblo Bonito. Several Navajo people are also buried there. In 1954, Richard Wetherill's family donated a large collection of artifacts to the University of New Mexico.

Images for kids

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |