Ridge and furrow facts for kids

Ridge and furrow is a special pattern of bumps (called ridges) and dips (called furrows) that you can still see in some fields today. This pattern was made a long time ago, during the Middle Ages, when farmers used a certain way of ploughing their land. It's like a historical clue left behind in the ground!

This way of farming was common in Europe, especially with the open-field system, where many farmers shared large fields. The earliest examples of ridge and furrow are from right after the Roman period. Farmers kept using this method until about the 1600s in some places, as long as the open-field system was still around.

Today, you can find these patterns in places like Great Britain, Ireland, and other parts of Europe. The ridges you see are usually parallel, meaning they run side-by-side. They can be from 3 to 22 yards (3 to 20 m) apart and up to 24 inches (61 cm) tall. When they were being used, they were much taller! Older patterns often have a gentle curve.

The ridge and furrow pattern formed because farmers used special ploughs that always turned the soil in the same direction. They ploughed the same strip of land year after year. You can only see these patterns on land that was ploughed in the Middle Ages but hasn't been ploughed since. If land is still being ploughed today, the old ridge and furrow patterns would have been smoothed out.

The ridges, sometimes called lands, were important. They helped farmers divide their land, measure how much work the ploughman did, and harvest their crops in the autumn.

Contents

How Ridge and Furrow Was Made

Imagine a traditional plough from the Middle Ages. It had a part called a ploughshare and another called a mould-board on the right side. This meant that when the plough moved, it always turned the soil over to the right.

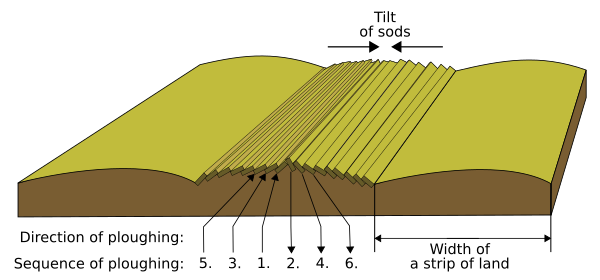

Because of this, the plough couldn't just go back and forth on the same line. Instead, farmers would plough in a big circle, going clockwise around a long, rectangular piece of land called a strip or land. After ploughing one long side of the strip, the farmer would lift the plough out of the ground at the end of the field. Then, they would move it across the unploughed area at the end of the strip, called the headland. After crossing the headland, they would put the plough back in the ground to work their way down the other long side of the strip.

The strips were kept fairly narrow. This made it easier to move the plough across the headland without having to drag it too far. Each time the field was ploughed, this process slowly moved the soil in each half of the strip one furrow's-width closer to the center line.

In the Middle Ages, each family managed their own strip within large open fields that were shared by everyone. The strips stayed in the same place every year. So, year after year, the soil kept moving towards the center of each strip. This gradually built up the middle of each strip into a ridge. Between these ridges, a dip or "furrow" was left. (This "furrow" is different from the small groove left by each pass of the plough.)

The raised ridges were helpful because they provided better drainage in wet weather. Water would drain into the furrows. If the field was on a slope, the water would collect in a ditch at the bottom. Only on very well-drained soils were fields left flat. In damper parts of the furrows, farmers might plant crops like peas or beans, which could handle more water, instead of wheat which might get waterlogged.

The dips between the ridges often marked the boundary between different farmers' plots. These strips varied in size, but they were traditionally about a furlong (which is 220 yards or about 200 meters) long. They could be from about 5 yards (4.6 m) up to a chain wide (22 yards or about 20 meters). This meant each strip covered an area of about 0.25 to 1 acre (0.1 to 0.4 ha).

In most places, farming continued over the centuries. Newer ploughing methods, especially the reversible plough, smoothed out the old ridge and furrow patterns. However, in some areas, the land was turned into grassland and hasn't been ploughed since. In these places, the old patterns have often been saved. Surviving ridge and furrow can have a height difference of 18 to 24 in (0.5 to 0.6 m) in some spots, making the landscape look wavy. When they were actively used, the height difference was even greater, sometimes over 6 feet (1.8 m)!

Curved Strips and Oxen

In the early Middle Ages, farmers used large teams of small oxen to pull their ploughs. A typical team might have eight oxen in four pairs. The plough itself was also big, mostly made of wood. Because the team and plough together were very long, it created a special effect in the ridge and furrow fields.

When the leading oxen reached the end of a furrow, they would turn left along the headland. The plough, pulled by the stronger oxen at the back, would keep going as long as possible in the furrow. By the time the plough finally reached the end, the oxen would be lined up, facing left along the headland. Each pair would then turn around to walk right along the headland, crossing the end of the strip. Then they would start down the opposite furrow. By the time the plough reached the beginning of the new furrow, the oxen were already lined up and ready to pull it forward.

This way of turning caused the end of each furrow to twist slightly to the left. This made these older ridge and furrows look like a gentle reverse-S shape. You can still see this S-shape in some places today, even in curved field boundaries, even if the ridge and furrow pattern itself has disappeared.

Turning left was the easiest way for the oxen. If they had turned right, they would have immediately had to turn right again into the next furrow. This would make the line of oxen cut across the top of the ploughed strip, pulling the plough out of the ground too early. It also would have been difficult with two lines of oxen moving in opposite directions so close together. Turning left allowed them to make one turn at a time and avoid awkward sideways movements.

As oxen grew larger and ploughs became more efficient, farmers needed smaller teams. These smaller teams took up less space on the headland, making it easier to plough in straight lines. It became even easier when heavy horses were introduced to pull ploughs. Because of this, ridge and furrow patterns from the late Middle Ages are usually straight.

Where to Find Ridge and Furrow Today

Some of the best-preserved ridge and furrow patterns can be found in these English counties:

- Buckinghamshire

- Cambridgeshire

- County Durham

- Derbyshire

- Gloucestershire

- Lincolnshire

- Leicestershire

- Northamptonshire

- Nottinghamshire

- Oxfordshire

- Warwickshire

- West Yorkshire

In Scotland, a large area of about 400-600 acres of rig and furrow still exists outside the town of Airdrie.

Ridge and furrow often survives on higher ground. This is because in the 1400s, much of this farmland was changed into land for sheep. Since then, it hasn't been ploughed by modern methods. Today, these areas are still used as pasture for sheep, and you can clearly see the wavy patterns, especially when the sun is low in the sky or after a light snowfall. These patterns are often found near deserted medieval villages, which are old villages that people left a long time ago.

Similar Land Patterns

There are other land patterns that might look a bit like ridge and furrow, but they were made in different ways or for different reasons:

- Cord rig: These are cultivation ridges made by digging with spades, not ploughs.

- Lazy beds: Similar to cord rig, these are also cultivation ridges created by hand-digging with spades.

- Lynchets: These are sloping terraces found on steep hillsides. They were formed by gravity on slopes that were ploughed.

- Raised bed gardening: This is a modern way of gardening where cultivated land is raised above the surrounding ground.

- Run rig and rundale: These were Scottish and Irish land-use patterns named after their characteristic ridges and furrows, but they involved different ways of sharing and using land.

- Water-meadows: These are grasslands with ridges and dips designed to control irrigation (how water flows to crops). They might look a bit like ridge and furrow, but their purpose and how they were made were very different.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |