Alexander Scriabin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Scriabin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin

25 December 1871 (N.S. 6 January 1872) |

| Died | 14 April 1915 (aged 43) Moscow, Russian Empire

|

| Occupation | Composer and pianist |

|

Notable work

|

List of compositions by Alexander Scriabin |

| Spouse(s) | Vera Ivanovna Isakovich Tatiana Fyodorovna Schlözer |

| Children | 7, including Ariadna Scriabina and Julian Scriabin |

| Signature | |

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (born January 6, 1872 – died April 27, 1915) was a famous Russian composer and amazing pianist. He was known for his unique and innovative music. At first, his music sounded a lot like Frédéric Chopin's, with a romantic and traditional style. But later, Scriabin created his own special sound. His music became more complex and used unusual harmonies.

Scriabin was also very interested in ideas like synesthesia, where you might "see" colors when you hear music. He even connected different musical notes to specific colors. Many people consider him a key figure in Russian Symbolism, a movement in art and literature. Even though his fame faded after his death, his music has become popular again since the 1970s.

Contents

About Alexander Scriabin

Early Life and Learning (1872–1893)

Alexander Scriabin was born in Moscow, Russia, on Christmas Day in 1871 (which was January 6, 1872, by the modern calendar). His family was part of the Russian nobility. His mother was a talented concert pianist, but she sadly passed away when Alexander was only one year old.

After his mother's death, Alexander's father, who was studying Turkish, moved away. Young Alexander, often called Sasha, was raised by his grandmother, great-aunt, and aunt. His aunt, who played the piano, often played for him.

Scriabin was a very smart and curious child. He loved building pianos and even gave his homemade pianos to guests! He was quite shy with other kids but enjoyed attention from adults. He also put on plays and operas using puppets. He started piano lessons at a young age with Nikolai Zverev, a very strict teacher who also taught Sergei Rachmaninoff.

In 1882, Scriabin joined a military school, but he was excused from physical training because he was small and weak. This gave him more time to practice piano every day. He was a top student in his classes.

Later, Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory. He became a well-known pianist even though his hands were small. He once hurt his right hand while practicing very difficult pieces. This led him to write his first major work, his Piano Sonata No. 1, which he described as a "cry against God." Luckily, his hand eventually healed.

He graduated from the Conservatory in 1892 with a medal for piano playing. However, he didn't finish his composition degree because he disagreed with one of his teachers and didn't want to write music that didn't interest him.

Starting His Career (1894–1903)

In 1894, Scriabin performed his own music for the first time in St. Petersburg, and people loved it. That same year, a music publisher named Mitrofan Belyayev agreed to publish Scriabin's compositions.

In 1897, Scriabin married a pianist named Vera Ivanovna Isakovich. They toured Russia and other countries, and his concerts were very successful, especially one in Paris in 1898. That year, he also started teaching at the Moscow Conservatory, building his reputation as a composer. During this time, he wrote many piano pieces, including his first three piano sonatas and his only piano concerto.

For five years, Scriabin lived in Moscow. His former teacher, Vasily Safonov, conducted the first performances of Scriabin's first two symphonies. Around 1901 to 1903, Scriabin thought about writing an opera. He imagined a hero who was a philosopher, musician, and poet, declaring, "I am the goal of all goals!"

Life Outside Russia (1903–1909)

In 1904, Scriabin moved to Switzerland and began working on his Symphony No. 3. While there, he and his wife separated. He then traveled with Tatiana Fyodorovna Schloezer, a former student, and they had more children together. Sadly, one of their sons, Julian Scriabin, who was a very talented young composer, drowned at age 11.

With help from a wealthy supporter, Scriabin spent several years traveling through Europe and the United States. He continued to write orchestral pieces and started composing "poems" for the piano, a type of music he became famous for. In 1907, he lived in Paris and was part of concerts that promoted Russian music. Later, he moved to Brussels, Belgium.

Returning to Russia (1909–1915)

In 1909, Scriabin moved back to Russia for good. He kept composing, working on bigger and bigger projects. Before he died, he dreamed of creating a huge, multi-sensory performance called Mysterium. It was meant to be a week-long event in the Himalayas, combining music, scents, dance, and light to bring about a "new world." He only left sketches for this piece, but parts of it have since been completed and performed by other musicians.

His Final Days

Scriabin gave his last concert on April 2, 1915, in St. Petersburg. Critics praised his playing, saying his eyes "flashed fire" and his face "radiated happiness." Scriabin himself felt so lost in the music that he forgot he was playing for an audience.

He returned to Moscow on April 4. A small pimple on his lip, which he had noticed before, became infected. His temperature rose, and he had to cancel a concert. The infection worsened, poisoning his blood, and he became very ill. On April 14, 1915, at the age of 43, Alexander Scriabin passed away in his Moscow apartment.

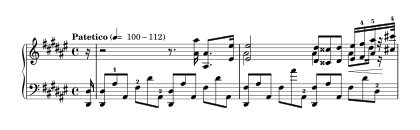

Scriabin's Music Style

Scriabin mostly wrote music for solo piano and for orchestra. His earliest piano pieces sound a lot like Frédéric Chopin's, including types of music like études (study pieces), preludes, and nocturnes (night pieces). However, Scriabin's musical style changed a lot during his life. His later works use very unusual and complex harmonies and textures.

You can see how his style changed by listening to his ten piano sonatas. The first ones are quite traditional, showing influences from Chopin and Franz Liszt. But the later sonatas are very different, with the last five not even having a traditional key signature. His music became more about creating a certain "color" or feeling with chords, rather than following strict traditional rules.

Early Music (1880s–1903)

In his early period, Scriabin's music followed the romantic style of the time. He used common harmonies, but he already showed his unique touch. He loved using dominant chords (chords that create tension and want to resolve) and adding extra notes to them.

Scriabin especially liked a type of dominant chord called the 13th dominant chord. He would often combine different versions of these chords, making them sound a bit more complex than usual for his time. However, he still used them in a traditional way, where the added notes would resolve, fitting within the usual rules of tonality.

Middle Music (1903–1907)

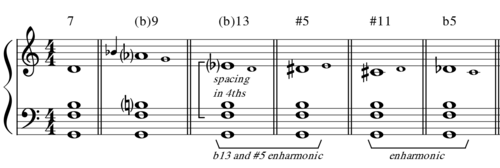

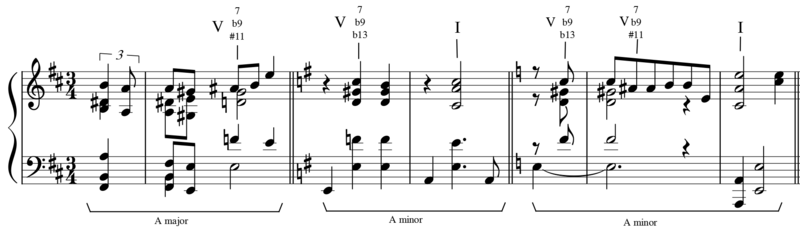

This period starts with Scriabin's Fourth Piano Sonata. During this time, his music became more colorful and dissonant (meaning it used notes that sound like they clash a bit). Even so, it still mostly followed traditional tonal rules. Scriabin wanted his music to sound bright and shining, and he did this by adding more notes to his chords.

In this period, you can start to hear hints of his famous mystic chord, but it still showed its roots in Chopin's style. At first, the clashing notes in his chords would resolve in a traditional way. But slowly, Scriabin started to leave these notes unresolved. The added notes became part of the chord's "color" rather than needing to resolve.

Late Music (1907–1915)

In his later music, Scriabin's style became even more unique. The traditional sense of a "key" almost disappeared. He still used dominant chords, but he moved them around in ways that made the music feel less tied to a single key.

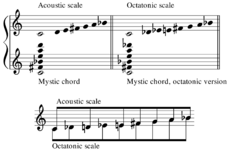

A music expert named Varvara Dernova explained that in Scriabin's late works, the main "tonic" (the home note of a key) still existed, but it was more like an idea in the composer's mind rather than something you actually heard clearly. Most of the music from this period is built on special scales like the acoustic and octatonic scales.

Ideas and Color in Music

Scriabin was very interested in philosophical ideas, including Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of the "Übermensch" (a superior human being). Later, he became fascinated by Theosophy, a spiritual philosophy. Both of these ideas greatly influenced his music and his way of thinking about it. He believed that the artist had a special role in understanding and celebrating life.

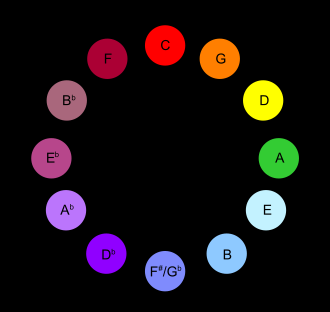

Scriabin is often linked to synesthesia, which is when your senses mix, like seeing colors when you hear sounds. However, it's thought that Scriabin didn't actually experience synesthesia in the usual way. Instead, his system of connecting colors to musical keys was a thoughtful idea, based on the circle of fifths and even Sir Isaac Newton's ideas about light.

He didn't see a difference between a major and minor key with the same starting note (like C major and C minor). Influenced by Theosophy, he developed his color system for his grand, unfinished project, Mysterium. This was meant to be a week-long performance in the Himalayas that would combine music, scent, dance, and light. He believed it would bring about a joyful end to the world.

The composer Sergei Rachmaninoff once talked with Scriabin and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov about Scriabin's color-music ideas. Rachmaninoff was surprised that Rimsky-Korsakov also agreed that musical keys had colors, even though they didn't always agree on which color went with which key. For example, both thought D major was golden-brown. But Scriabin thought E-flat major was red-purple, while Rimsky-Korsakov thought it was blue.

Scriabin wrote only a few orchestral pieces, but they are very famous. These include his piano concerto and five symphonic works. One of his most famous pieces, Prometheus: The Poem of Fire (1910), included a part for a special machine called a "clavier à lumières" or Luce (meaning "light"). This was a colour organ that played like a piano but projected colored light onto a screen instead of making sound. Most performances of the piece didn't use the light, but some did, including one in New York City in 1915.

Today, Scriabin's original color keyboard is kept in his apartment in Moscow, which is now a museum dedicated to his life and works.

Recordings and Performers

Scriabin himself made recordings of 19 of his own works using piano rolls. These recordings, made in 1910, allow us to hear how he played his own music. They show that he liked to play with a lot of freedom, changing the speed, rhythm, and loudness as he felt right.

Many famous pianists have performed Scriabin's music. Some of the most well-known include Vladimir Sofronitsky, Vladimir Horowitz, and Sviatoslav Richter. Sofronitsky never met Scriabin, but he married Scriabin's daughter, Elena. Horowitz once played for Scriabin when he was 11 years old, and Scriabin was very impressed, encouraging him to continue his musical studies.

Many pianists have recorded all of Scriabin's piano sonatas, including Vladimir Ashkenazy and Marc-André Hamelin. Other great performers of his piano music include Emil Gilels and Evgeny Kissin.

Family and Descendants

Scriabin was the uncle of Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) of Sourozh, a respected bishop in the Russian Orthodox Church in Great Britain. He was not related to the Soviet politician Vyacheslav Molotov, even though Molotov's birth name was also Skryabin.

Scriabin had seven children in total. Four were from his first marriage: Rimma, Elena, Maria, and Lev. Three were from his relationship with Tatiana Fyodorovna Schlözer: Ariadna, Julian, and Marina. Sadly, Rimma and Lev both passed away at age seven. Elena Scriabina later married the famous pianist Vladimir Sofronitsky.

Scriabin's daughter Ariadna Scriabina (1906–1944) became a hero of the French Resistance during World War II. She was honored with awards like the Croix de Guerre for her bravery. She helped with communications and transporting supplies for the resistance fighters, and she died during a mission in 1944.

Ariadna Scriabina's daughter, Betty Knut-Lazarus, also became a teenage hero in the French Resistance, receiving awards for her courage. After the war, she moved to Israel. One of Scriabin's great-grandsons, Elisha Abas, is an Israeli concert pianist.

Julian Scriabin, Alexander's son, was a child prodigy in music, but he tragically drowned at age 11 in Ukraine.

See also

In Spanish: Aleksandr Skriabin para niños

In Spanish: Aleksandr Skriabin para niños

- List of compositions by Alexander Scriabin

- 20th-century classical music

- Silver Age of Russian Poetry

- Symbolism

- Theosophy

- ANS synthesizer

- Atonality

- Music written in all 24 major and minor keys

- Mystic chord

- Romantic music

- Synesthesia in art

- Synthetic chord