Vladimir Horowitz facts for kids

Vladimir Samoylovich Horowitz (October 1 [O.S. September 18] 1903 – November 5, 1989) was a famous Russian-born American classical pianist. Many people think he was one of the greatest pianists ever. He was known for his amazing playing skills, the beautiful sound he made, and how excited audiences got when he performed.

Contents

Early Life and Piano Journey

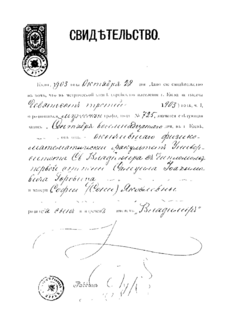

Vladimir Horowitz was born on October 1, 1903, in Kiev. At that time, Kiev was part of the Russian Empire. His birth certificate clearly states Kiev as his birthplace.

He was the youngest of four children. His parents, Samuil Horowitz and Sophia Bodik, were Jewish but did not strictly follow religious rules. His father was an electrical engineer. To make Vladimir seem younger and protect his hands from military service, his father changed his birth year to 1904. This date appeared in many books during Horowitz's life.

When Horowitz was 10, he played for a famous composer named Alexander Scriabin. Scriabin told his parents that Vladimir was extremely talented.

Horowitz started learning piano very young from his mother, who was also a pianist. In 1912, he joined the Kiev Conservatory. He studied with Vladimir Puchalsky, Sergei Tarnowsky, and Felix Blumenfeld. His first solo concert was in Kharkov in 1920.

He soon began touring Russia and the Soviet Union. Because of the Russian Civil War, he was often paid with food like bread, butter, and chocolate instead of money. In one season (1922–23), he performed 23 concerts in Petrograd alone. Even with his early success, he wanted to be a composer. He said he became a pianist only to help his family, who had lost their belongings in the Russian Revolution.

In December 1925, Horowitz left for Germany. He said he was going to study, but he secretly planned not to return to Russia. He hid American dollars and British pound notes in his shoes to pay for his first concerts.

Becoming Famous in the West

On December 18, 1925, Horowitz played his first concert outside Russia in Berlin. He then performed in Paris, London, and New York City. The Soviet Union wanted him to represent them at a piano competition in Poland in 1927, but he chose to stay in the West.

Horowitz made his United States debut on January 12, 1928, at Carnegie Hall. He played Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1. The audience loved his performance. A critic from The New York Times said Horowitz's playing was like "a tornado unleashed." The critic also noted that Horowitz had a special way of exciting his audience, which he kept throughout his career.

In 1933, he played with the famous conductor Arturo Toscanini for the first time. They performed Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5. Horowitz and Toscanini played together many times after that. Horowitz moved to the U.S. in 1939 and became an American citizen in 1944. He appeared on TV for the first time in 1968, in a concert filmed at Carnegie Hall.

Even with great success, Horowitz sometimes felt unsure about his playing. He struggled with his mental health and took breaks from public performances. He stopped playing from 1936 to 1938, 1953 to 1965, 1969 to 1974, and 1983 to 1985.

Recording His Music

Horowitz made many recordings throughout his career. In 1926, he made some early recordings in Germany. His first recordings in the United States were in 1928.

In 1930, he recorded Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 3 in Europe. This was the first time that piece had ever been recorded. He continued to record solo piano music in the UK until 1936. From 1940, he focused on recording in the US.

During one of his breaks from performing (1953-1965), he recorded music at his home in New York City. His first stereo recording was in 1959.

In 1962, Horowitz started recording for Columbia Records. His most famous recordings from this time include his 1965 return concert at Carnegie Hall and a 1968 recording from his TV special.

He returned to RCA in 1975 and made live recordings until 1983. In 1985, he signed with Deutsche Grammophon and continued to record until 1989. His last recording was finished just four days before he passed away. All of his recordings are now available on compact disc.

Teaching Students

Horowitz taught seven students between 1937 and 1962. Some of his notable students were Byron Janis, Gary Graffman, and Ronald Turini. Janis said that Horowitz treated him like a son.

Horowitz later said he only had three main students: Janis, Turini, and Graffman. He explained that some others played for him for a few months, but he stopped working with them if they didn't improve enough. In the 1980s, he also coached established pianists like Murray Perahia and Eduardus Halim.

Personal Life

In 1933, Horowitz married Wanda Toscanini, who was the daughter of conductor Arturo Toscanini. They came from different religious backgrounds, but it wasn't an issue because neither was very religious. They mostly spoke French because Wanda didn't know Russian, and Horowitz knew little Italian. Wanda was very important to Horowitz. She was one of the few people whose opinions he trusted about his playing. She stayed with him during times when he felt very down and didn't want to leave the house. They had one daughter, Sonia Toscanini Horowitz (1934–1975). Sonia was badly hurt in a motorbike accident in 1957 but survived. She passed away in 1975.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Horowitz received medical treatment for his depression.

In 1982, Horowitz started taking antidepressant medications. During this time, his playing seemed to decline. His performances in 1983 had some memory lapses and less physical control. He stopped playing in public for two years after this.

Later Years and Return to Russia

In 1985, Horowitz stopped taking medication and returned to performing and recording. His first appearance was in a documentary film called Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic. In his later concerts, he focused more on delicate playing and beautiful sounds, though he could still perform difficult pieces. Many critics felt his performances after 1985 were some of his best later works.

In 1986, Horowitz announced he would return to the Soviet Union for the first time since 1925. He gave concerts in Moscow and Leningrad. These concerts were very important for both music and politics, as they showed a new spirit of understanding between the USSR and the US. Most tickets for the Moscow concert were for important Soviet officials, so few were sold to the public. This led to many music students sneaking into the concert, which was even heard by people watching on TV. The Moscow concert was released as an album called Horowitz in Moscow, which was very popular.

After his Russian concerts, Horowitz toured several European cities. Later that year, President Ronald Reagan gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is the highest award a civilian can receive in the United States.

Horowitz's last tour was in Europe in the spring of 1987. His final public concert was in Hamburg, Germany, on June 21, 1987. This concert was recorded but not released until 2008. He continued to record music until he passed away.

Death

Vladimir Horowitz died on November 5, 1989, in New York City. He was 86 years old and died from a heart attack. He was buried in his wife's family tomb in Milan, Italy.

His Music Style and Technique

Horowitz was most famous for playing Romantic piano music. Many people believe his 1932 recording of the Liszt Sonata in B minor is still the best version, even after more than 80 years. He was also known for playing Scriabin's Étude in D-sharp minor, Chopin's Ballade No. 1, and many short pieces by Rachmaninoff. Rachmaninoff himself was amazed by Horowitz's playing of his Piano Concerto No. 3.

Horowitz also played quieter, more gentle pieces. These included Schumann's Kinderszenen, and sonatas by Scarlatti, Clementi, Mozart, and Haydn. His recordings of Scarlatti and Clementi are highly valued. He helped bring interest back to these two composers, whose works were not often played in the early 20th century.

During World War II, Horowitz supported new Russian music. He was the first in America to play piano sonatas by Prokofiev and Kabalevsky. He also premiered works by American composer Samuel Barber.

He was known for his versions of Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsodies. His Second Rhapsody was recorded in 1953 and he said it was the hardest of his arrangements. Horowitz also created his own versions of other composers' pieces, like his Variations on a Theme from Carmen and The Stars and Stripes Forever by John Philip Sousa. The Sousa piece became a favorite encore for audiences.

Horowitz sometimes changed parts of compositions if he thought it would make them sound better on the piano. For example, he rewrote parts of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition. He believed Mussorgsky, not being a pianist, didn't fully understand the instrument's possibilities. Composers whose works Horowitz played, like Rachmaninoff and Prokofiev, often praised his performances even when he made changes to their scores.

While audiences loved Horowitz's playing, some critics did not. They sometimes called his playing "exaggerated." However, many other pianists, like Martha Argerich and Maurizio Pollini, greatly admired him.

Horowitz's style included huge changes in loudness, from very loud to very soft. He could make a lot of sound from the piano without it sounding harsh. He also created a wide range of different tones. He was famous for his fast and precise octave playing. When asked how he practiced octaves, he showed that he practiced them just like everyone else was taught.

Horowitz's hand position was unusual. His palm was often below the keys. He often played chords with straight fingers. Despite his exciting playing, he rarely lifted his hands high above the piano.

Awards and Recognitions

Vladimir Horowitz received many awards for his incredible talent.

Grammy Award for Best Classical Performance – Instrumental Soloist or Soloists (with or without orchestra)

- 1968 Horowitz in Concert: Haydn, Schumann, Scriabin, Debussy, Mozart, Chopin

- 1969 Horowitz on Television: Chopin, Scriabin, Scarlatti, Horowitz

- 1987 Horowitz: The Studio Recordings, New York 1985

Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist(s) Performance (with orchestra)

- 1979 Golden Jubilee Concert, Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3

- 1989 Horowitz Plays Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 23

Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra)

- 1963 Columbia Records Presents Vladimir Horowitz

- 1964 The Sound of Horowitz

- 1965 Vladimir Horowitz plays Beethoven, Debussy, Chopin

- 1966 Horowitz at Carnegie Hall – An Historic Return

- 1972 Horowitz Plays Rachmaninoff (Etudes-Tableaux Piano Music; Sonatas)

- 1973 Horowitz Plays Chopin

- 1974 Horowitz Plays Scriabin

- 1977 The Horowitz Concerts 1975/76

- 1979 The Horowitz Concerts 1977/78

- 1980 The Horowitz Concerts 1978/79

- 1982 The Horowitz Concerts 1979/80

- 1988 Horowitz in Moscow

- 1991 The Last Recording

- 1993 Horowitz Discovered Treasures: Chopin, Liszt, Scarlatti, Scriabin, Clementi

Grammy Award for Best Classical Album:

- 1963 Columbia Records Presents Vladimir Horowitz

- 1966 Horowitz at Carnegie Hall: An Historic Return

- 1972 Horowitz Plays Rachmaninoff (Etudes-Tableaux Piano Music; Sonatas)

- 1978 Concert of the Century with Leonard Bernstein (conductor), the New York Philharmonic, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Vladimir Horowitz, Yehudi Menuhin, Mstislav Rostropovich, Isaac Stern, Lyndon Woodside

- 1987 Horowitz: The Studio Recordings, New York 1985

- 1988 Horowitz in Moscow

Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, 1990

Other Awards:

- 1970 – Prix Mondial du Disque for Kreisleriana

- 1972 – Honorary Member of the Royal Academy of Music (London)

- 1982 – Wolf Foundation Prize for Music

- 1985 – Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur from the French Government

- 1985 – Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

- 1986 – United States Presidential Medal of Freedom

- 2012 – Gramophone Hall of Fame entrant

See also

In Spanish: Vladimir Horowitz para niños

In Spanish: Vladimir Horowitz para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |