Seaton Sluice facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Seaton Sluice |

|

|---|---|

Seaton Sluice Harbour |

|

| Population | 2,956 |

| OS grid reference | NZ3477 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WHITLEY BAY |

| Postcode district | NE26 |

| Dialling code | 0191 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Northumberland |

| Ambulance | North East |

| EU Parliament | North East England |

| UK Parliament |

|

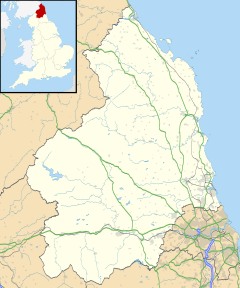

Seaton Sluice is a village located on the coast in Northumberland, England. It sits where the small Seaton Burn river meets the sea. The village is found between Whitley Bay and Blyth. In 2021, about 2,956 people lived in Seaton Sluice.

Contents

How Seaton Sluice Got Its Name

Seaton Sluice is about half a mile north of Hartley village. It was once part of Hartley and known as Hartley Pans. This name came from the "salt-pans" used to make salt there since 1236. Hartley was a larger area, stretching from the Brier Dene Burn to the Seaton Burn. This land once belonged to Tynemouth Priory, a religious house.

Around 1100, the land became the property of Hubert de Laval, who was related to William the Conqueror. The de Lavals (also called Delavals) settled about half a mile inland from Hartley Pans. Their home became Seaton Delaval. The name 'Seaton' comes from an old English word meaning a settlement by the sea.

Improving the Harbour for Ships

Before 1550, salt made at Hartley Pans was sent to Blyth to be shipped out. After that, it was shipped directly from the small, natural harbour. The village then became known as Hartley Haven. It was used to export both coal and salt.

However, the harbour often filled with sand, making it hard for ships to get in. Sir Ralph Delaval (1622–1691) solved this problem. He built a pier and special gates that held back seawater at high tide. When the tide was low, the gates opened, and the water rushed out, washing the sand away. Because of this clever system, the village became known as Seaton Sluice.

The harbour stayed this way until the 1760s. Then, Sir John Hussey Delaval made a big change. He blasted a new channel through solid rock for the harbour entrance. This new channel was called 'The Cut'. It was 54 feet deep, 30 feet wide, and 900 feet long.

The new channel opened in 1763. This made the land between the old harbour entrance and the new channel into an island, called 'Rocky Island'. A small bridge connected Rocky Island to the mainland. The new channel could be closed at both ends. This meant ships could be loaded no matter what the tide was doing. On the other side of the old channel was a hill called Sandy Island. This hill was made from the sand and rocks that ships used as ballast (weight) when they entered the harbour empty. Both Sandy Island and The Cut can still be seen today.

The new entrance worked very well. By 1777, ships leaving the harbour carried 80,000 tonnes of coal, 300 tons of salt, and 1.75 million glass bottles. Coal was brought to the harbour from nearby mines using wagonways, where horses pulled the coal wagons. Salt continued to be exported from Seaton Sluice until 1798. At that time, a new tax on salt ended the trade.

The Royal Hartley Bottleworks

In 1763, Sir Francis Blake Delaval (1727–1771) got permission from Parliament to build glassworks on 25 acres of land at Seaton Sluice. This factory was called 'The Royal Hartley Bottleworks'. Sir Francis needed skilled glassmakers. His brother, Tom Delaval, brought experts from Germany to teach the local workers how to make glass.

The factory used materials found nearby. This included sea sand, sea kelp, clay from the coast, and local coal. The glassworks grew over time. It eventually had six large cone-shaped furnaces that stood tall against the sky. They were named Gallagan, Bias, Charlotte, Hartley, Waterford, and Success. The three biggest cones were 130 feet tall. By 1777, the factory made 1,740,000 bottles each year.

The bottles were sent down to the harbour using narrow railways that ran through tunnels. These tunnels were later used as air-raid shelters during the Second World War. The bottles were carried to London on special 'bottle sloops'. These ships were a bit smaller than coal ships, about 50 feet long. A special feature was that their main mast could be lowered. This allowed them to pass under the arches of old London Bridge. A bottle sloop would make one trip to London and back each month. Bottles were also sent to other countries in Europe.

The bottleworks were so large that they had their own market, a brewery, a place to store grain, a brickyard, a chapel, shops, pubs, and a quarry. The workers lived in stone houses on several streets around the factory. In 1768, a shipyard was also built.

However, other glass-making factories started to compete. This led to fewer orders, and the bottleworks closed in 1872. The last bottles left on a ship called the 'Unity of Boston', heading for the Channel Islands. A few years later, in 1897, the tall cone-shaped furnaces were torn down and houses were built in their place. Today, there is almost no sign of the original bottleworks.

Changes in the Coal Trade

Even with the improvements made by the Delaval family, the harbour at Seaton Sluice could only handle smaller ships. Meanwhile, other ports like Blyth to the north and the Tyne to the south spent money to make their docks better. The new Northumberland Dock on the Tyne was finished in 1857. Seaton Sluice found it hard to compete with these bigger ports.

Another big problem for the coal trade from Seaton Sluice was the Hartley Colliery Disaster. This happened at the Hester Pit in the village of New Hartley, about 2 miles west of Seaton Sluice. The Hester Pit was the main source of local coal. In 1862, the engine that pumped water out of the mine broke. Its heavy beam fell down the only mine shaft, blocking it. This trapped 204 men and boys underground, and sadly, they all died. In some cases, several people from the same family were lost. This disaster led to a new law: all future mines had to have at least two shafts for safety. The loss of coal from the Hester Pit meant the end of the coal trade from Seaton Sluice. The village became a quiet place. There is a tall memorial stone for the 204 men and boys in the graveyard of St Alban’s Church in the nearby village of Earsdon.

In the early 1900s, there was an attempt to make Seaton Sluice a tourist spot. A railway line was planned to go north up the coast from Whitley Bay. It was partly built but then stopped when the First World War began. You can still see parts of the old railway bridges and raised ground west of St Mary's Island.

Seaton Delaval Hall: A Grand House

The Delaval family settled at Seaton Delaval, which is inland from Seaton Sluice. There was already an Anglo-Saxon church there. The Delavals built a strong, fortified house near it. In 1100, Hubert de la Val rebuilt the Saxon church into the Church of Our Lady, which stands today. The fortified house slowly grew into a large manor house during the Tudor and Jacobean periods.

In the early 1700s, the manor house was replaced by the grand Seaton Delaval Hall. This new hall was designed by the famous architect Sir John Vanbrugh. In 1822, a fire badly damaged the hall. It was partly fixed up and is now owned by the National Trust.

Places of Interest in Seaton Sluice

Seaton Sluice has several interesting places, including historic pubs:

- The King’s Arms – This is the oldest pub in the village. It is right next to the bridge that leads to Rocky Island. It was built in the mid-1700s as a house for the harbour manager, but later became a pub.

- The Waterford Arms – This pub is located above the quay. It is named after Susanna, Marchioness of Waterford. She was Lord Delaval's granddaughter and inherited the estate in 1822. The pub stands where a brewery used to be. That brewery made beer for the ships and the glassworkers.

- The Melton Constable – Built in 1839, this pub is on the north side of the burn. It is named after Melton Constable, a town in Norfolk. This town is linked to the Astley family, who inherited the Delaval estates in 1814.

- The Delaval Arms – You can find this pub at the south end of Hartley.

- The Astley Arms – This pub is at the north end of Seaton Sluice. It is also named after the Astley family.

There is also the Seaton Sluice Working Men's Club, located near the Waterford Arms.

The Octagon is a small, castle-like building east of the Waterford Arms. It is a Grade II listed building, meaning it's important historically. It was built before 1750 and used to be the Harbour Office. Some people think Sir John Vanbrugh designed it, but there is no clear proof. Today, it is a private art gallery.

Seaton Delaval Hall, designed by Sir John Vanbrugh and built between 1718 and 1729 for Admiral George Delaval, is just outside Seaton Sluice. It is a Grade I listed building and is now owned by the National Trust. Visitors can explore it on certain days.

Near Seaton Delaval Hall is the Church of Our Lady. The Delaval family built this church in the 12th century, and it was changed in the 14th and 19th centuries. It is also a Grade I listed building.

Holywell Dene is a valley with many trees where the Seaton Burn river flows towards Seaton Sluice. There are paths along the river, looked after by a group called 'Friends of Holywell Dene'. On the north side of the valley, there is a ruined building called 'Starlight Castle'. This was built by Sir Francis Delaval in 1750. Legend says he built it after betting he could build a home for a friend in one day. Since it was a stone building with many arches, he probably lost the bet!

North of the harbour mouth, past Sandy Island, are Blyth Sands. This is a wide, sandy beach with sand dunes behind it, stretching all the way to Blyth Harbour.

Images for kids

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |