Shintaro Ishihara facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Shintarō Ishihara

|

|

|---|---|

|

石原 慎太郎

|

|

Ishihara in 2009 at governor's office

|

|

| Governor of Tokyo | |

| In office 23 April 1999 – 31 October 2012 |

|

| Preceded by | Yukio Aoshima |

| Succeeded by | Naoki Inose |

| Minister of Transport | |

| In office 6 November 1987 – 27 November 1988 |

|

| Prime Minister | Noboru Takeshita |

| Preceded by | Ryūtarō Hashimoto |

| Succeeded by | Shinji Satō |

| Director General of the Environment Agency | |

| In office 24 December 1976 – 28 November 1977 |

|

| Prime Minister | Takeo Fukuda |

| Preceded by | Shigesada Marumo |

| Succeeded by | Hisanari Yamada |

| Member of the House of Councillors for National Block |

|

| In office 8 July 1968 – 25 November 1972 |

|

| Member of the House of Representatives for Tokyo 2nd district |

|

| In office 10 December 1972 – 18 March 1975 |

|

| In office 10 December 1976 – 14 April 1995 |

|

| Member of the House of Representatives for Tokyo PR Block |

|

| In office 11 December 2012 – 21 November 2014 |

|

| Preceded by | Ichirō Kamoshita |

| Succeeded by | Akihisa Nagashima |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 September 1932 Suma-ku, Kobe, Japan |

| Died | 1 February 2022 (aged 89) Ōta, Tokyo, Japan |

| Cause of death | Pancreatic cancer |

| Political party | Liberal Democratic (1968–1973, 1976–1995) Independent (1973–1976, 1995–2012) Sunrise (2012) Japan Restoration (2012–2014) Future Generations (2014–2015) |

| Spouse | Noriko Ishihara |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | Hitotsubashi University |

| Profession | Novelist, author |

Shintaro Ishihara (石原 慎太郎, Ishihara Shintarō, 30 September 1932 – 1 February 2022) was a Japanese politician and writer. He served as the Governor of Tokyo from 1999 to 2012. He was known for his strong views on Japanese politics and its relationship with other countries.

Besides his political career, Ishihara was also a successful writer and artist. He won awards for his novels and wrote best-selling books. He also worked in theater, film, and journalism. One of his famous books, The Japan That Can Say No, encouraged Japan to be more independent from the United States.

Ishihara started his career as a writer and film director. Later, he became a politician, serving in Japan's parliament (the House of Councillors and the House of Representatives) before becoming Governor of Tokyo. He left the governorship to lead a new political party and returned to parliament briefly before retiring from politics.

Contents

Early Life and Artistic Career

Shintaro Ishihara was born in Suma-ku, Kobe, Japan. His father worked for a shipping company. Shintaro grew up in Zushi, Kanagawa. In 1952, he started studying at Hitotsubashi University, graduating in 1956.

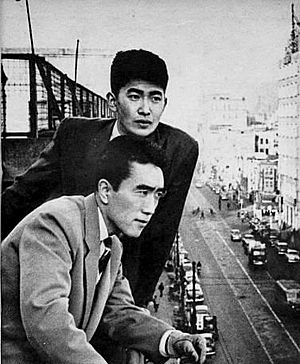

Just two months before he graduated, Ishihara won the Akutagawa Prize. This is Japan's most important literary award. He won it for his novel Season of the Sun. His brother, Yujiro Ishihara, acted in the movie version of the novel, for which Shintaro wrote the script. Shintaro also directed a few films starring his brother.

In the early 1960s, he focused on writing. He wrote plays, novels, and even a musical version of Treasure Island. He also ran a theater company. Outside of writing, he was an adventurer! He visited the North Pole, raced his yacht, and rode a motorcycle across South America. He wrote a book about his motorcycle journey.

From 1966 to 1967, he worked as a reporter covering the Vietnam War. This experience helped him decide to enter politics.

Becoming a Politician

In 1968, Ishihara ran for a seat in the House of Councillors, which is part of Japan's parliament. He was part of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). He received a huge number of votes, more than any other LDP candidate at that time.

After four years, he moved to the House of Representatives, another part of parliament. He won that election too.

In 1975, Ishihara ran for Governor of Tokyo. He lost to the person who was already governor, Ryokichi Minobe. Ishihara returned to the House of Representatives. He then held important government jobs, like Director-General of the Environment Agency and Minister of Transport.

In the 1980s, Ishihara was a very well-known and popular figure in the LDP. In 1989, he wrote a book called The Japan That Can Say No with Sony chairman Akio Morita. This book became famous in the West. It encouraged Japan to be more assertive with the United States.

Governor of Tokyo

In 1999, Ishihara ran for Governor of Tokyo again, this time as an independent candidate. He won the election. As governor, he made several important changes:

- He cut down on some big spending projects in Tokyo.

- He introduced new taxes, like a tax on banks' profits and a tax on hotel stays.

- He put rules in place to limit diesel-powered vehicles. He even held up a bottle of diesel soot to show how much pollution they caused.

- He suggested opening casinos in the Odaiba area of Tokyo.

- He led Tokyo's bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympics, though Tokyo lost to Rio de Janeiro.

- He helped set up a bank called ShinGinko Tokyo to lend money to small and medium-sized businesses in Tokyo.

- He was Chairman of Tokyo's successful bid to host the 2020 Summer Olympics.

Ishihara was re-elected as Governor of Tokyo in 2003, 2007, and 2011. He was a very popular governor.

On October 25, 2012, Ishihara announced he would step down as Governor of Tokyo. He wanted to form a new political party for national elections. His resignation was approved, and he officially left his role as governor on October 31, 2012. He had been governor for over 13 years, making him the second-longest serving Governor of Tokyo.

Forming New Political Parties

After leaving the governorship, Ishihara helped form a new national political party called the Sunrise Party. He then merged this party with another group, the Japan Restoration Party. Ishihara became the head of this new, larger party.

In December 2014, he ran for election again with the Party for Future Generations. However, he was not re-elected. After this, he officially retired from politics.

Political Views

Ishihara was known for his strong, sometimes controversial, political views. He was often described as a right-wing politician. He was connected to the Nippon Kaigi organization, which promotes traditional Japanese values.

Foreign Relations

Ishihara often said that Japan's foreign policy was not strong enough. He believed Japan should stand up for itself more, especially in its relationship with the United States. He even wrote a book with the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad, about Asia saying "No" to Western countries.

He was also critical of the government of People's Republic of China. He invited important figures like the Dalai Lama and the President of Taiwan, Lee Teng-hui, to Tokyo.

Ishihara was very concerned about the issue of Japanese citizens being kidnapped by North Korea. He called for economic penalties against North Korea. Later, when Tokyo was bidding for the 2016 Olympics, he eased his criticism of China. He even attended the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing and carried the Olympic torch in Japan.

Views on Foreigners in Japan

Ishihara sometimes made comments about foreigners in Japan that caused controversy. For example, in 2000, he spoke about people who had entered Japan illegally. He suggested they might cause problems if a natural disaster happened in Tokyo. These comments led to calls for his resignation and concerns among people of Korean descent in Japan. The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination also criticized his remarks.

In 2012, Ishihara suggested that Tokyo should buy the Senkaku Islands. These islands are claimed by both Japan and China, and his proposal caused tension between the two countries. Japan's government later bought the islands to try and prevent further issues.

Personal Life

Ishihara was married to Noriko Ishihara. They had four sons. Two of his sons, Nobuteru Ishihara and Hirotaka Ishihara, also became members of Japan's parliament. His second son, Yoshizumi Ishihara, is an actor and weatherman. His youngest son, Nobuhiro Ishihara, is a painter. His younger brother, Yujiro Ishihara, was a famous actor.

In April 2011, Ishihara was a survivor of the major earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster that hit Japan on March 11, 2011.

Illness and Death

In January 2022, Shintaro Ishihara was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He passed away at his home in Tokyo on February 1, 2022, at the age of 89.

Books Written by Ishihara

- Taiyō no kisetsu (太陽の季節), Season of the Sun, Winner of the Akutagawa Prize, 1956

- Kurutta kajitsu (狂った果実), Crazed Fruit, 1956

- The Japan That Can Say No (in collaboration with Akio Morita), 1989

- Otōto (弟), Younger brother, Mainichi Publishing Culture Award Special Award, 1996

- Hi no shima (火の島), Island of Fire, 2008

Film Career

Shintaro Ishihara acted in six films, including Crazed Fruit (1956) and The Hole (1957). He also helped direct the 1962 film Love at Twenty with famous directors like François Truffaut.

Honours

- Akutagawa Prize (1956)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (2015)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (2015)

See also

In Spanish: Shintarō Ishihara para niños

In Spanish: Shintarō Ishihara para niños

- Ethnic issues in Japan

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |