St. Clair's defeat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of the Wabash |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Northwest Indian War | |||||||

Arthur St. Clair |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Northwestern Confederacy | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

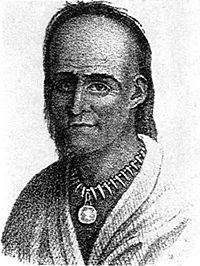

| Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, Buckongahelas |

Arthur St. Clair, Richard Butler † William Darke |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,100 | 1,400 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 21 killed 40 wounded total: 61 |

632 soldiers killed or captured 264 soldiers wounded 24 workers killed, 13 workers wounded total: 933 (not including women and children) |

||||||

The Battle of the Wabash, also known as St. Clair's Defeat, was a major battle fought on November 4, 1791. It took place in the Northwest Territory of the United States. In this battle, the U.S. Army fought against a group of Native American tribes called the Western Confederacy. This battle was part of the Northwest Indian War. It was the biggest defeat ever for the American military against Native American forces.

Native American leaders like Little Turtle of the Miamis, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees, and Buckongahelas of the Delawares led over 1,000 warriors. The American force, led by General Arthur St. Clair, had about 1,000 soldiers. The Native American warriors attacked at dawn, surprising St. Clair's men. Only 24 of the 1,000 American officers and soldiers escaped without harm. Because of this huge loss, President George Washington made St. Clair resign. The U.S. Congress also started its first investigation into the government's actions.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

After the American Revolutionary War ended in 1783, the Treaty of Paris gave the United States control over land east of the Mississippi River. This included the area known as the Old Northwest. However, the Native American tribes living there were not part of this treaty. Many leaders, like Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, did not agree with the U.S. claim to their lands.

The new U.S. government needed money after the war. They planned to sell land in the Northwest Territory to raise funds. This plan meant that Native American villages and settlers living on the land without permission would have to move. During the 1780s, American settlers and travelers faced many attacks. About 1,500 people died in these conflicts. White settlers often fought back against Native Americans. This cycle of violence made it hard for new settlers to move into the area. So, some leaders asked President Washington to use the military to stop the Miami tribe.

In 1790, a force of 1,453 American soldiers, led by General Josiah Harmar, marched north. This mission, known as the Harmar campaign, was a disaster for the U.S. Native American forces ambushed Harmar's troops, causing over 200 American casualties. Harmar's army had to retreat.

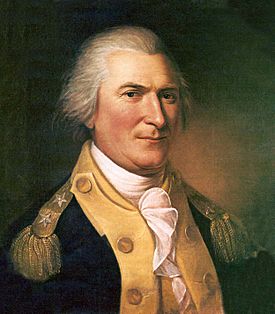

President Washington then ordered General Arthur St. Clair to try again in 1791. St. Clair was also the governor of the Northwest Territory. Congress agreed to create a second group of regular soldiers. But they later cut the soldiers' pay, which made it hard to find enough people. St. Clair had to add Kentucky militia and other temporary soldiers to his army.

In May 1791, Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson led a raid. He hoped to distract the Native American tribes while St. Clair marched north. Wilkinson's raid killed 9 Native Americans and captured 34, including a daughter of Little Turtle. Many Native American leaders were thinking about making peace. But when they heard about Wilkinson's raid, they decided to prepare for war instead. Wilkinson's raid actually brought the tribes together against St. Clair.

Who Led the Armies

The Native American forces did not have one single leader. Both Blue Jacket and Little Turtle later said they were in charge. When the battle started, the Shawnee tribe led the attack. Little Turtle is often given credit for the victory.

The different Native American groups stood in a crescent (moon) shape. Little Turtle (Miami), Blue Jacket (Shawnee), and Buckongahelas (Lenape) were in the middle. Egushawa led the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe on the left side. Tarhe and Simon Girty led the Wyandot, Mingo, and Cherokee on the right side.

The United States Army was led by Major General Arthur St. Clair. His main commanders included:

- 1st Infantry Regiment - Major Jean François Hamtramck

- 2nd Infantry Regiment - Major Jonathan Hart (killed in action)

- Artillery Battalion - Major William Ferguson (killed in action)

- U.S. levies - Major General Richard Butler (killed in action)

- 1st Levy Regiment - Lieutenant Colonel William Darke

- 2nd Levy Regiment - Lieutenant Colonel George Gibson

- Kentucky militia - Lieutenant Colonel William Oldham (killed in action)

The March to Battle

President Washington wanted St. Clair to move north in the summer. But St. Clair faced many problems getting ready at Fort Washington (now Cincinnati, Ohio). The new soldiers were not well trained. Food supplies were bad, and there were not enough good horses. So, the expedition did not start until October 1791. The army built supply posts as they went. Their goal was Kekionga, the main village of the Miami tribe.

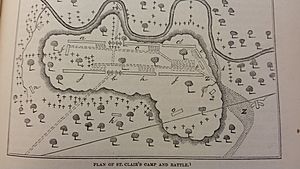

St. Clair's army started with about 2,000 men. But many soldiers left, and others got sick. By the time they set out, there were only about 1,486 soldiers and 200-250 camp followers (like wives and children). They moved slowly, and soldiers often disobeyed orders. St. Clair, who was sick with gout, found it hard to keep order. Native Americans watched the army constantly, and small fights broke out. By November 2, St. Clair's force had shrunk to about 1,120 people.

While St. Clair's army got smaller, the Western Confederacy grew stronger. Buckongahelas brought 480 men to join Little Turtle and Blue Jacket's 700 warriors. This made their war party more than 1,000 warriors, including many Potawatomis.

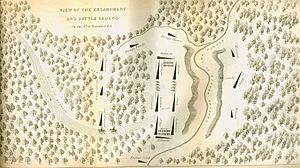

On November 3, St. Clair had 52 officers and 868 soldiers ready for duty. That day, the army camped on a high meadow. The soldiers were on one side of the Wabash River, and the Kentucky militia were on the other. This made it hard for them to help each other. They did not build any defenses, even though Native Americans had been seen nearby. A small group of soldiers saw some warriors and reported that an attack was coming. But this warning was not sent to St. Clair, and defenses were not increased.

The Battle Begins

On the evening of November 3, St. Clair's army set up camp on a hill near where Fort Recovery, Ohio is today. A Native American force of about 1,000 warriors, led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, surrounded the camp in a large crescent shape. They waited in the woods until dawn.

At dawn, the American soldiers were getting ready for their morning meal. Suddenly, the Native Americans attacked. They surprised the Americans and quickly took over their camp. The Miami, Shawnee, and Lenape warriors first attacked the militia. The militia fled across the Wabash River and up the hill to the main camp, leaving their weapons behind.

The regular soldiers quickly grabbed their muskets and formed lines. They fired at the Native Americans, pushing them back. But the Native American forces on the left and right sides moved around the American soldiers. They closed in on the main camp, completely surrounding it within 30 minutes. The American muskets and cannons were not very good. They did little harm to the Native American warriors, who were hidden behind trees. St. Clair's cannons were on a nearby hill. But the Native American marksmen killed the cannon crews, and the remaining soldiers had to disable their guns.

Women and children with the army hid among the supply wagons. Some militia tried to join them, but the women forced them back into the fight. Colonel Darke ordered his soldiers to attach their bayonets (knives on the end of rifles) and charge the main Native American position. Little Turtle's forces moved back into the woods, but then they surrounded Darke's soldiers and defeated them. The Americans tried this bayonet charge many times, but it always ended the same way. St. Clair had three horses shot from under him as he tried to rally his men.

The Retreat

After three hours of fighting, St. Clair gathered his remaining officers. Facing total defeat, he decided to try one last bayonet charge to break through the Native American lines and escape. They left supplies and wounded soldiers behind. As before, Little Turtle's army let the bayonets pass through. But this time, the American soldiers ran for Fort Jefferson. Those who could run fastest left the slow and wounded behind.

A group of soldiers from Pennsylvania tried to protect the rear of the retreating army. But when their leader was wounded, they fled. With no organized defense, the retreat quickly became a wild escape. St. Clair later wrote that the path was covered with discarded weapons and uniforms. Soldiers threw away anything that slowed them down. One cook even left her baby behind. Another story says a baby left in the snow was found and adopted by the Native Americans.

One soldier, Stephen Littell, got lost and accidentally returned to the empty camp. He reported that the Native Americans were gone, chasing the fleeing army. The wounded soldiers who remained begged him to kill them before the Native Americans returned. The Native Americans continued to chase the Americans, killing those who fell behind. After about four miles, they returned to loot the camp. Littell, hiding, saw them eat the abandoned food, divide the spoils, and kill the wounded.

The first of the retreating soldiers reached Fort Jefferson that evening, almost 30 miles away. The fort was too small and had no food. So, those who could walk had to continue to Fort Hamilton, another 45 miles away. The wounded were left at Fort Jefferson with little or no food. Those on horseback reached Fort Hamilton the next morning, followed by those who walked.

On November 11, St. Clair sent supplies and 100 soldiers from Fort Washington. They found 116 survivors at Fort Jefferson eating "horse flesh and green hides." A relief party of Kentucky militia was organized, but it broke up without taking action. In January 1792, Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson led a supply convoy to Fort Jefferson. His group tried to bury the dead and collect the missing cannons. But there were "upwards of six hundred bodies" at the battle site and at least 78 bodies along the road. It was too big a task. The exact number of wounded is not known, but it was reported that fires burned for several days after the battle to burn bodies.

Many Casualties

The number of American soldiers killed in St. Clair's defeat was the highest percentage ever for a U.S. Army unit. St. Clair's second-in-command, Richard Butler, was among the dead. Of the 52 officers, 39 were killed and 7 were wounded. This means about 88% of all officers were hurt or killed. Among the soldiers, 97% were casualties. This included 632 out of 920 killed (69%) and 264 wounded. Nearly all of the 200 camp followers were also killed. In total, 832 Americans died. About one-quarter of the entire U.S. Army was wiped out. Only 24 of the 920 officers and men escaped unharmed.

So many people died that when 300 soldiers returned to the site in 1793, they found the area by the unburied human remains. They had to move bones to make space for their beds. The soldiers buried the remains in a large grave. Sixty years later, in 1851, the town organized a "Bone Burying Day" to bury more bones found there. Historian William Hogeland called this Native American victory "the high-water mark in resistance to white expansion."

What Happened Next

The large number of U.S. soldiers killed in St. Clair's defeat was more than three times the number killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn 85 years later. Even though it was one of the worst disasters in U.S. Army history, St. Clair's loss is mostly forgotten today.

The battle site is now the town of Fort Recovery, Ohio. It has a cemetery, a memorial, and a museum. One important result of the Native American victory was that the United States decided to create a larger, professional army. It also led to changes in the militia. The investigation into the battle also helped create the idea of executive privilege, which allows the president to keep some information private. The 1795 Treaty of Greenville used the battle site to draw a line. This line opened most of modern Ohio for U.S. settlement.

The Battle in Stories and Songs

Years after the defeat, a story was published about a skeleton and diary found inside a tree in Miami County, Ohio. The story claimed they belonged to a Captain Roger Vanderberg. However, no one by that name died in the 1791 battle. This story actually came from a Scottish novel.

A folk song called "St. Clair's Defeat" (or "Sinclair's Defeat") became popular in the 1800s. It might have been based on an earlier song about Crawford's Defeat by the Indians. Music historians say the song was written by a blind poet named Dennis Loughey around 1800. It has been recorded by several folk musicians over the years.

The battle, along with the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, is also a likely source for the name of the fife and drum song "Hell on the Wabash."