Stanislav Petrov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stanislav Petrov

|

|

|---|---|

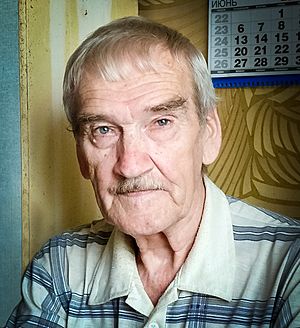

Petrov at his house in 2016

|

|

| Born |

Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov

7 September 1939 |

| Died | 19 May 2017 (aged 77) |

| Known for | 1983 Soviet nuclear false alarm incident |

| Spouse(s) | Raisa Petrova (m. 1973; died 1997) |

| Children | 2 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

Soviet Air Defence Forces |

| Years of service | 1972–1984 |

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel |

Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov (Russian: Станисла́в Евгра́фович Петро́в; 7 September 1939 – 19 May 2017) was a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet Air Defence Forces. He became famous for his actions during the 1983 Soviet nuclear false alarm incident.

On 26 September 1983, Petrov was the officer on duty at a secret command center. This center used a system called Oko to detect if missiles were launched from other countries. The system suddenly reported that the United States had launched a missile, and then up to five more. Petrov had to decide what to do.

He believed the reports were a false alarm, meaning they were wrong. His decision went against military rules at the time. Many people believe his choice stopped a huge nuclear war from happening. If he had reported the missiles as real, the Soviet Union might have launched its own attack. This could have led to a global conflict that would have caused terrible damage. Later, an investigation proved that the warning system had indeed made a mistake. Because of his actions, Petrov is often called "the man who saved the world."

Contents

Early Life and Military Service

Stanislav Petrov was born on 7 September 1939, near Vladivostok, in Russia. His father was a pilot who flew fighter aircraft during World War II. His mother worked as a nurse.

Petrov studied at the Kyiv Military Aviation Engineering Academy. After finishing his studies in 1972, he joined the Soviet Air Defence Forces. In the early 1970s, he started working with a new early warning system. This system was designed to spot ballistic missile attacks from NATO countries.

Petrov was married to Raisa, and they had two children, a son named Dmitri and a daughter named Yelena. His wife passed away from cancer in 1997.

The False Alarm Incident

On that important night, the Soviet warning system showed missiles coming from the United States. However, nuclear attacks usually need many sources to confirm them. Petrov felt that something was wrong with the system's report. He decided it was a false alarm.

It turned out he was right. No missiles were launched. The computer system had made a mistake. Experts later found that the false alarm happened because of a rare event. Sunlight reflected off high-altitude clouds above North Dakota. This light then hit the satellites in their special Molniya orbits, making them think missiles were there. This error was later fixed.

Petrov later explained why he thought it was a false alarm:

- He knew a real US attack would likely be a massive strike, not just five missiles.

- The missile detection system was new, and he didn't fully trust it yet.

- The warning message went through many checks too quickly.

- Ground radars did not show any missiles, even after some time.

Petrov said his training as a civilian helped him make the right choice. He believed other soldiers, with only military training, might have followed the rules and reported a real launch.

After the incident, Petrov was questioned a lot by his commanders. At first, he was praised for his decision. General Yury Votintsev, who was in charge of missile defense, said Petrov's actions were "correct." However, Petrov also received a warning for not filling out paperwork correctly. He had not written down the incident in the official war diary.

He did not receive a reward. Petrov believed this was because the incident showed problems with the missile detection system. Rewarding him would have meant punishing the people who designed it. He was moved to a less important job. He later retired early, though he said he was not forced out of the army. He also suffered from stress after the event.

Petrov later mentioned that the famous "red button" to launch nuclear missiles was never truly active. Military experts did not want one person to have that much power.

The world only learned about this incident in 1998. That's when General Votintsev wrote about it in his memoirs. Since then, many news reports have shared Petrov's story.

Some people debate exactly how much power Petrov had. He could not have launched missiles himself. His job was to watch the satellite system and report warnings up the chain of command. The top Soviet leaders would then decide whether to attack. But Petrov's report was very important for that decision.

Bruce G. Blair, an expert on nuclear strategies, said that in 1983, the Soviet Union was very tense. They were ready to react quickly to an attack. He said the false alarm happened at a very dangerous time.

Petrov later said he never imagined facing such a situation. He called it the first and only time something like that happened, outside of practice drills.

Later Life and Recognition

After the incident, the Soviet government looked into what happened. They found that Petrov had not properly written down his actions during the crisis. He explained that he had a phone in one hand and an intercom in the other, and couldn't write. Still, he received a warning.

In 1984, Petrov left the military. He then worked at the research institute that created the early warning system. He later retired to care for his wife, who had cancer.

In May 2007, Petrov visited the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in the United States. This was a former enemy missile base. He said he never thought he would visit such a place.

Stanislav Petrov passed away on 19 May 2017, from hypostatic pneumonia. He was 77 years old. His death was not widely reported until September of that year.

Awards and Honors

On 21 May 2004, an organization called the Association of World Citizens gave Petrov their World Citizen Award. He received a trophy and $1,000 for helping to prevent a disaster. In January 2006, Petrov traveled to the United States. He was honored at the United Nations in New York City. There, he received another special World Citizen Award. The next day, Petrov met famous American journalist Walter Cronkite.

His trip to the United States was filmed for a movie called The Man Who Saved the World. This film, directed by Peter Anthony, came out in October 2014. It won awards at the Woodstock Film Festival.

Petrov received the Dresden Peace Prize in Dresden, Germany, on 17 February 2013. The award included €25,000. On 24 February 2012, he was given the 2011 German Media Award in Baden-Baden, Germany.

On 26 September 2018, after his death, Petrov was honored in New York with the $50,000 Future of Life Award. Former United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon spoke at the ceremony. He said it was hard to imagine anything worse than a nuclear war between Russia and the United States. He added that this might have happened by accident if not for Petrov's wise decisions. Petrov's daughter, Elena, accepted the award.

The Russian Federation's mission to the UN stated that one person could not have started or stopped a nuclear war. They said that many systems and reports are needed to confirm an attack. However, nuclear security expert Bruce G. Blair disagreed. He said the Soviet Union was very tense and ready to react quickly. He believed the false alarm happened at a very dangerous time in US-Soviet relations.

Petrov himself was humble about his actions. In the film The Man Who Saved the World, he said, "All that happened didn't matter to me—it was my job. I was simply doing my job, and I was the right person at the right time, that's all." He even said his wife didn't know about it for 10 years. When she asked what he did, he replied, "Nothing. I did nothing."

See also

In Spanish: Stanislav Petrov para niños

In Spanish: Stanislav Petrov para niños

- Vasily Arkhipov – a Soviet naval officer who refused to launch a nuclear torpedo during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

- List of nuclear close calls